• Equal Rights Amendment: President Joe Biden announces that the Equal Rights Amendment should be considered a ratified addition to the U.S. Constitution. It’s unclear if the statement will have any impact.

• Biden commutes sentences: President Joe Biden announces that he is commuting the sentences of almost 2,500 people convicted of nonviolent drug offenses, nullifying prison terms he deemed too harsh.

• Supreme Court sustains TikTok ban: The Supreme Court unanimously upholds the federal law banning TikTok beginning Jan. 19 unless it’s sold by its China-based parent company.

• SpaceX rocket explodes: A SpaceX Starship rocket breaks up minutes after launching from Texas, setting back Elon Musk’s flagship rocket program.

• China population decline: China’s population fell last year for the third straight year, pointing to further demographic challenges for the world’s second-most populous nation.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

A ceasefire in the Middle East would seem to signify, at long last, a chance for new beginnings. But in talking to people in Israel and Gaza, Taylor Luck and Ghada Abdulfattah suggest something less clear in their powerful report today.

The uncertainty that has defined the war is not so easily shaken off. First, the long breath, held for some 15 months, must find some space merely to exhale into days not filled by pounding fear. People must reestablish some sense of their own humanity, a beginning to a beginning.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

News briefs

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

A deeper look

( 12 min. read )

With his reelection, Donald Trump cements his place as one of the most significant leaders of the 21st century. When his story is fully told, it will be for ushering in a new era that upended American life, both politically and culturally.

( 6 min. read )

Over more than 15 months of war and loss, Israeli and Palestinian emotions have been rubbed raw, or suppressed. Now they are being released by an imminent ceasefire, even as questions over its durability persist.

( 7 min. read )

Our reporter surveys fire-gutted homes and businesses in her neighborhood in Altadena, California, and ponders the future of this microcosm of Greater Los Angeles.

( 5 min. read )

Many assume that because Donald Trump has an affinity for Vladimir Putin, his policies mirror those of the Russian president. In the case of ending the war in Ukraine, at least, there is a yawning gulf between the two men’s outlooks.

On Film

( 3 min. read )

“I’m Still Here” is a movie about remembrance – of a family and a nation, our critic writes of the drama based on real events. “The necessity to acknowledge injustice is its timeless clarion call.”

In Pictures

( 2 min. read )

Climate change is overheating the Sahara. A revival of traditional mud-brick houses could help protect one city and its people.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

When he hired Jackie Robinson to break the racial barrier in baseball in 1947, Branch Rickey, president of the Brooklyn Dodgers at the time, described having two things on his mind. “My only purpose is to be fair to all people,” he said, “and my selfish objective is to win baseball games.”

The marriage of equality and excellence in American sport has been a gradual and uneven project ever since. While racial barriers have fallen on the field, integration has taken far longer to reach the manager’s office. Two recent hirings mark how that is changing.

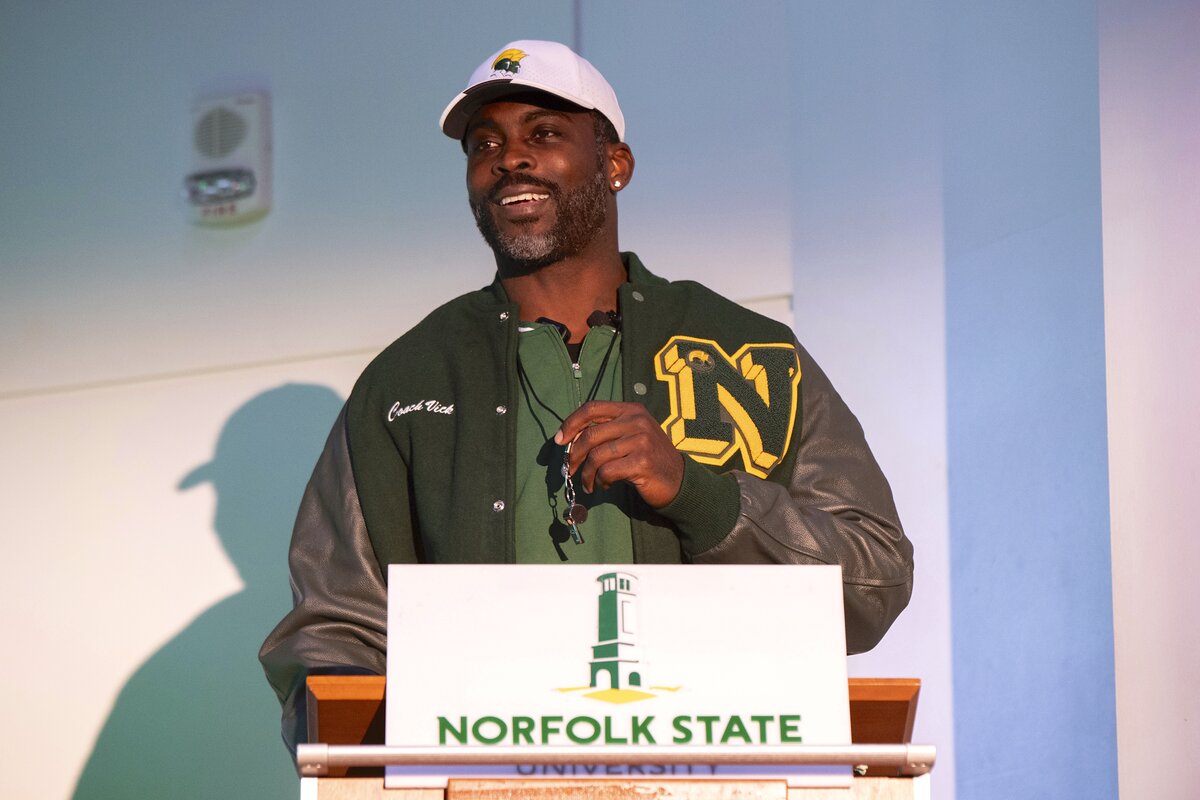

In December, two historically Black schools, Delaware State University and Norfolk State University in Virginia, each tapped a former professional player to run its football program. The appointments confirm something of a trend. Five years ago, Jackson State University, a historically Black school in Mississippi, hired former NFL star Deion Sanders as head coach.

Like Mr. Sanders, DeSean Jackson and Michael Vick were hired to fix losing teams. Like Mr. Sanders, they start with little coaching experience. But they bring – as Mr. Sanders did – personal records of broken records. In just two years, Mr. Sanders led a team that had six consecutive losing seasons to a 12-1 record in 2022.

Delaware and Norfolk are hoping for similar transformations. Their desire to build winning programs is rooted in a deeper purpose. According to the National Collegiate Athletics Association, the number of Black football head coaches “is only about a third of what one might expect given the share of Black student-athletes in football.”

The country’s HBCUs were created to cultivate academic excellence and promote advancement for formerly enslaved people and their descendants. The schools now hope to achieve the same outcomes in athletics. As Bishop Kim Brown, a member of Norfolk’s board of visitors, said when Mr. Vick was introduced, “Today, we put on full display the mission of HBCUs, especially our school. We provide opportunity.”

Leveling opportunity in sport, on the field as well as on the sidelines, writes David Grenardo, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, breaks down barriers by showing that excellence has nothing to do with identity. It is innate in all individuals, as Mr. Sanders tells his players, and is nurtured through discipline, humility, and selflessness.

“Sports provide a reflection of society and its many facets, which include racism,” Professor Grenardo wrote in the Harvard Journal of Sports & Entertainment Law in 2021. “Sports can also reflect the beauty of society through healing and transforming the world in a positive manner.”

On Monday, the University of Notre Dame’s Marcus Freeman will be the first Black head coach to lead a team into the national college football championship. That milestone might have held a particular poignance for Branch Rickey. When everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed, all of society wins.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 1 min. read )

We experience the omnipotence of divine Love as we open our hearts to loving even our enemies.

Viewfinder

James Wright (l.), a sophomore at Owensboro High School, learns how to weld a bead on a beam from Collin Baldwin, a pipe welder for Envision Contracting, during an annual Construction Career Day, Thursday, Apr. 24, 2025, in Owensboro, Ky. There's a growing push for high school students to consider vocational programs rather than four-year colleges, the cost of which has grown 181% since 1989-90 – even after adjusting for inflation, according to the Education Data Initiative.

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us this week. Next Monday will be the Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday in the United States, which means we would normally be taking the day off. But it also happens to be Inauguration Day for President-elect Donald Trump. So we will be sending you a special newsletter on that topic Monday. The regular Daily will return Tuesday.