What Trump’s return says about this moment in America

Loading...

| Washington

Micki Witthoeft wipes a tear from her eye and apologizes.

“I’m sorry; it’s an emotional time,” says Ms. Witthoeft, standing outside the Central Detention Facility in Washington, D.C.

She’s the mother of Ashli Babbitt, the rioter who was shot dead by law enforcement during the Jan. 6, 2021, storming of the U.S. Capitol by supporters of President Donald Trump.

Why We Wrote This

With his reelection, Donald Trump cements his place as one of the most significant leaders of the 21st century. When his story is fully told, it will be for ushering in a new era that upended American life, both politically and culturally.

It’s a chilly Christmas Eve, and about 20 people are standing outside the Washington jail, taking part in the nightly vigil supporting those still being held here for their actions on that day. What does Ms. Witthoeft expect from President-elect Trump when he takes office again Jan. 20?

“I believe he will keep his word, and he will start the process to either commute sentences or pardon people,” Ms. Witthoeft says. She began the vigils Aug. 1, 2022, after “Ashli talked to me in my dream.”

That the nightly protests have lasted nearly 900 days is a testament to the participants’ passionate support for those sometimes known as J6ers. And they’re but one example of how Mr. Trump – even out of office – has been a uniquely dominant force in American public life since the day in June 2015 he rode down the golden escalator in Trump Tower to announce his run for president.

By then, Mr. Trump was already famous as a New York real estate developer and reality TV personality. But when his story is fully told, it will be for ushering in a new era that has upended American life, both politically and culturally.

Ironically, by losing his first bid for reelection in 2020 – making way for a four-year “interregnum” with President Joe Biden, and then pulling off the first nonconsecutive presidential reelection since Grover Cleveland in 1892 – Mr. Trump has extended his public dominance by four years.

At the launch of his second term, political analysts say, the stakes are even higher than when he took office eight years ago.

“The times are more fraught globally and more fraught economically,” says Matthew Dallek, a political historian at George Washington University. “The divisions and level of rancor and vitriol and political violence have intensified since he was first in office.”

Last summer’s two assassination attempts on Mr. Trump are high-profile examples. So, too, is the killing of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson on a Manhattan street in December. Several top Trump appointees have faced bomb threats, according to the president-elect’s transition team. Overall, threats against public officials have risen over the past decade.

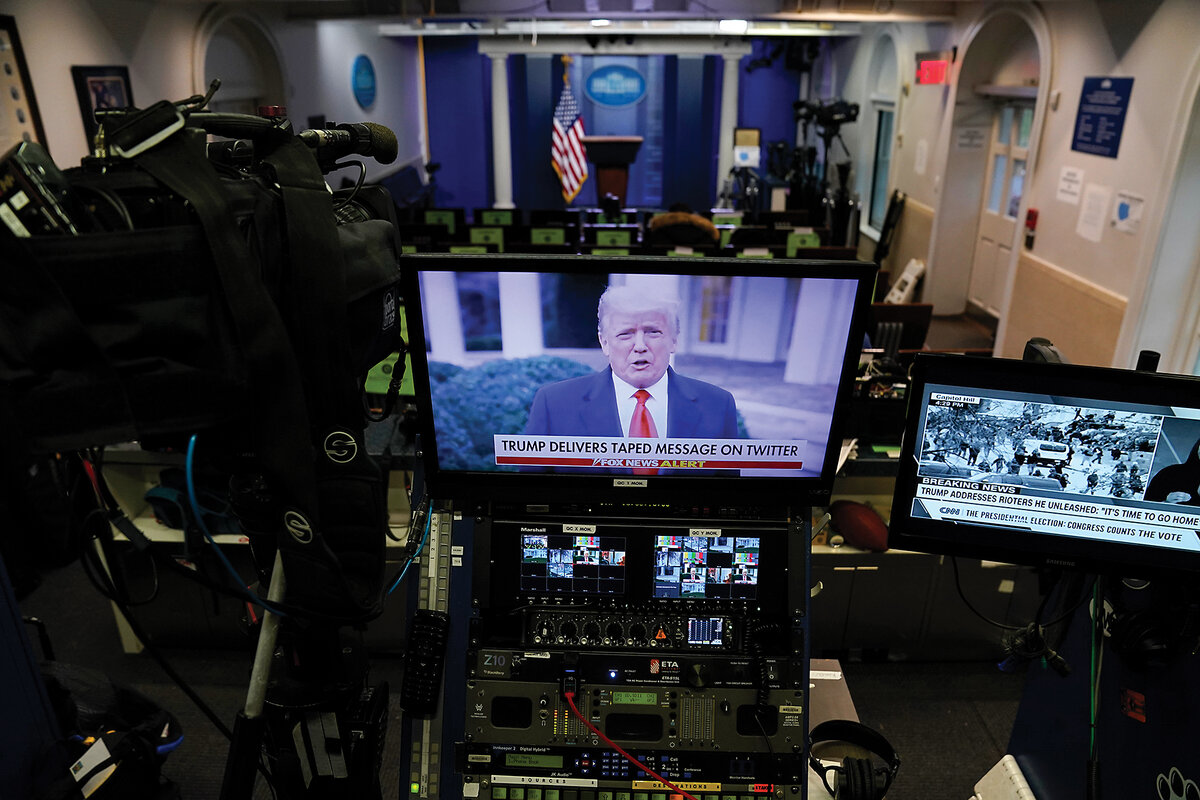

More broadly, Mr. Trump has stayed in the public spotlight virtually nonstop since losing reelection in 2020, claiming repeatedly and falsely that the election was stolen, and then staging an improbable comeback in November. A clear example of Mr. Trump’s dominance came a year ago – well before clinching the 2024 nomination – when he lobbied successfully to kill a bipartisan Senate deal on immigration, effectively holding on to the issue for his campaign.

The various criminal and civil cases against him also kept him in the headlines, and may well have helped him win last November as he cried legal persecution. With Mr. Trump now poised to become the 47th president, most of those cases have evaporated.

It is within this atmosphere of ferment that long-simmering talk on the left of a potential “Trump dictatorship” persists. Mr. Trump himself seems to revel in the speculation, telling Fox News late in 2023 that he wouldn’t be a dictator if elected again – “except on Day 1.”

Indeed, the opening act of the Trump sequel promises to be momentous. The president-elect has said the message of his second inaugural will be “unity” – a sharp departure, if true, from the dystopian picture of “American carnage” he painted in his first.

Next will come dozens of executive actions – at once typical for a new president, and in Mr. Trump’s case, expected to reflect the transformative intent of the second term. Beyond the anticipated pardons of J6ers, other measures include the closing of the U.S.-Mexico border, the start of mass deportations of unauthorized migrants, the removal of job protections for thousands of federal employees, and expanded oil drilling. (Explore more Trump promises for Day 1.)

When asked how the second term will differ from the first, a Trump insider – speaking not for attribution so as to speak freely – puts it this way: “He knows what he’s doing. This time around, it’s not just pie in the sky.”

The shock and awe of Trump 2.0

In fact, the shock and awe of Trump 2.0 began soon after Election Day. A string of highly controversial Cabinet picks consumed public discourse. Matt Gaetz, a now-former Florida congressman and Trump loyalist, withdrew from consideration for attorney general amid serious ethics concerns, including reports (later detailed in a House Ethics Committee report) of paying for sex with a minor and of drug use.

Mr. Trump’s aggressive posture toward the mainstream media is perhaps just a foretaste of his pledge to seek “retribution” and prosecute so-called enemies, including President Biden, special counsel Jack Smith, and former Wyoming Rep. Liz Cheney.

In December, he settled a defamation lawsuit against ABC News and George Stephanopoulos for $15 million, after the host inaccurately stated that Mr. Trump had been “found liable for rape” in a civil case. Another lawsuit, against the Des Moines Register and others over a preelection poll that showed him losing in Iowa, will at a minimum cost the defendants in legal fees, if not have a chilling effect on less wealthy outlets going forward.

During an eight-week period before the election, Mr. Trump attacked the media publicly more than 100 times, according to the group Reporters Without Borders.

Another eyebrow-raising episode came in late December, when Mr. Trump revived the first-term idea of having the United States buy Greenland, a territory of Denmark – and of reclaiming control over the Panama Canal, which the U.S. began to cede to Panama in 1977. Such headline-grabbers may be just talk, designed to create leverage toward other goals. Indeed, Mr. Trump’s suggestion that Canada become the 51st state is widely seen as a joke, albeit one aimed at trolling the U.S.’s northern neighbor as the president-elect threatens tariffs. But at the very least, all the expansive suggestions present Mr. Trump as an empire-builder, astride the world stage.

More central to Trump 2.0 has been the rise of world’s-richest-man Elon Musk as both a sidekick and a governing force. Before the holidays, it was Mr. Musk who led the charge in Congress, via his own social platform X, killing the first attempt at a compromise bill to keep the government funded – hours before Mr. Trump weighed in. A later bill passed, averting a shutdown.

Mr. Musk so dominated the shutdown narrative that critics dubbed the duo “President-elect Musk” and “Vice President-elect Trump.” The actual president, Mr. Biden, has receded publicly as he approaches retirement.

Mr. Musk’s stated role in the second Trump term is to co-lead, along with entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy, a new advisory commission called the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE. The intent is to recommend massive cuts in the federal bureaucracy and regulations.

But Mr. Musk has also been more than just an adviser to Mr. Trump. He’s effectively become part of the Trump family, taking part in phone calls with world leaders, reportedly weighing in on Cabinet choices, and often appearing with Mr. Trump at his Florida estate and at public events.

Can the bromance last? It’s impossible to say. A schism within the MAGA movement has emerged over the South African-native Mr. Musk’s support for granting visas to skilled foreign workers. Die-hard Trump supporters oppose all types of immigration. Late in December, Mr. Trump suggested support for H-1B visas for immigrant workers, but the issue remains an open question.

For now, the Musk factor looms large. The DOGE king’s megaphone is arguably as big as Mr. Trump’s, given the multibillionaire’s social media, and he has a much vaster bank account. Mr. Musk has also made clear he’ll deploy his cash in the 2026 midterms to take on Republican members of Congress who defy the president.

Isolationism, protectionism, and nativism

The rise and return of Mr. Trump haven’t happened in a vacuum. The world over, populists and strongmen have come to power amid continuing postpandemic economic disruption, increasing inequality, and growing anti-immigrant sentiment.

David M. Kennedy, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian at Stanford University, remembers the words of President George W. Bush in an Oval Office meeting with scholars back in 2006.

“‘There are three things happening in this country that really bother me, and I’d like to hear your perspective: isolationism, protectionism, and nativism,’” Professor Kennedy recalls President Bush saying.

“Well, here we are, 18, 19 years later, and you could name the same three items today,” Dr. Kennedy says.

But the Stanford scholar suggests that the idea of the U.S. sliding toward authoritarian rule is a stretch.

“The great preoccupation of the founders was the containment of power – the power of the legislature, the power of the executive, the power of the courts,” Dr. Kennedy says. “They built a system to guarantee that too much power would never end up in one place.”

Historian Tevi Troy, a senior aide in the second Bush White House, says he doesn’t see Mr. Trump as a “dictator,” instead pointing to a trend toward greater presidential power that began well before the Trump era.

“Congress has just ceded power over the past 20 years, and presidents have accumulated power as Congress cedes it,” says Mr. Troy, a senior fellow at the Ronald Reagan Institute.

Still, Mr. Trump’s ability to enact his agenda will have its limits. Elements that need to go through the newly seated House of Representatives will face the smallest margin of control in modern history, with just a four-seat Republican majority after the resignation of Mr. Gaetz. And the Senate is far from the 60 votes needed to overcome a filibuster, with a 53-47 Republican majority. The new GOP Senate leadership has promised to keep the filibuster in place.

Actions by Mr. Trump that wind up in federal court could well face a Biden-appointed judge; the president gained confirmation of a record 235 federal judges during his term. The Supreme Court’s 6-3 conservative majority can be expected to help Mr. Trump, but offers no guarantees.

Julia Azari, a political scientist at Marquette University in Wisconsin, also sees limits to the idea of absolute Trump rule, given the closely divided Congress. And despite Mr. Trump’s claims of a mandate, his victory last fall was not a sweep. He fell just short of a majority of the popular vote.

“The political minority is setting the agenda, and that sets us up for very deeply contentious politics,” Professor Azari says. That is true not just in partisan terms, but also demographically, she says, noting Mr. Trump’s inroads into both the Hispanic and Black communities.

Ultimately, she says, “Trump has created a political environment in which, even when he hasn’t commanded a national majority, people have to respond to him.”

“We are neighbors; we are civil people.”

Linda Jew is “overjoyed” by the 2024 election result.

“I said prayers every night for Donald Trump that he would be our president again,” says the Republican from Parker, Colorado.

Ms. Jew can trace her family back to a Chinese merchant who arrived in the 1800s. Now, in the city’s latest immigration chapter, Denver has tracked the arrival of nearly 43,000 migrants since late 2022. At home in Parker, some 20 miles south, Ms. Jew says illegal immigration is a chief concern. She doesn’t like how federal funds have been spent on migrants, including for temporary shelters.

“Biden is just giving away all our money” to unauthorized immigrants, she says. “And not helping the American citizens.”

Newsmax, Tucker Carlson, and Steve Bannon help her make sense of a changing world; she’s watched her state in recent decades trend from red to purple to blue. She says Mr. Trump’s campaign stop in Aurora, where he pledged to crack down on “migrant crime,” made her feel less alone.

The retired dental hygienist recalls one patient, years ago, scolding her for being conservative. He told her she was supposed to be a Democrat – as a woman and minority.

“You just reduced me to a stereotype,” she recalls replying. The man’s assumption cemented her beliefs all the more.

Still, it’s hard to talk with loved ones who disagree. Like the time a family member called Mr. Trump “Hitler” over the phone. Ms. Jew hung up. But that didn’t feel right. So she called back.

Farther west, in San Francisco, Kimberley Rodler is also still processing the election that was. During the campaign, the architect-turned-art-teacher traded in years of frequent flyer miles to travel to battleground states, from Nevada to Michigan to Pennsylvania, and canvass for the Democratic ticket. This reporter met her last fall in Florida, where abortion rights were on the ballot.

In all, Ms. Rodler says later on the phone, she knocked on 2,460 doors, and has no regrets – not that she loved every interaction. She recalls canvassing in Nevada the day of the Trump assassination attempt in Pennsylvania.

“I was confronted at two doors by Trump supporters with guns,” Ms. Rodler says. “I was wearing a Biden-Harris T-shirt or button, and this woman comes up and says, ‘Five minutes, if you’re not off my property, you’re shot!’”

Now Ms. Rodler is immersing herself in poetry and art, clinging to happier memories from the campaign, like the first-time voters she met who were grateful to be heard.

“I saw so much of the beauty of the people,” she says. “We are neighbors; we are civil people.”

Polls, in fact, show that Americans share much common ground, at least on issues if not on candidates. A preelection survey in six battleground states and nationally by the University of Maryland found bipartisan consensus on a range of issues – from the cost of living to reproductive rights to the border.

Still, the nation’s closely divided politics promise to make enacting the Trump agenda more difficult than he has suggested at times, from reducing inflation and cutting taxes to fixing the broken immigration system. As Inauguration Day approached, Mr. Trump sought to tamp down expectations.

For decadeslong Trump observers, this is a moment to take stock. Looking back to his days as a publicity-minded Manhattan businessman and reality TV performer, few could imagine the historic figure he’d become.

When Gwenda Blair was writing her 2000 book chronicling three generations of the Trump family, she says she grasped that Donald Trump had “a really acute understanding of American culture, politics, economics, the whole schmear, and was acutely laser-focused on what a large number of people really felt and really wanted to hear.”

“He is a consummate salesman,” says Ms. Blair. And in Mr. Trump’s final campaign, she says, she saw an understanding of the American psyche that has reached “a whole other cellular level.”

Back at the Washington Central Detention Facility on Christmas Eve, the mood outside on the sidewalk dubbed “Freedom Corner” is hopeful, even festive. Mr. Trump is about to retake office, and one of those imprisoned expresses optimism in a call to a participant’s cellphone, amplified for the assembled supporters to hear.

The U.S. Capitol, the scene four years ago of one of the most shocking episodes in American history, is just 2 miles down the road. But on this night, it feels a million miles away.

Staff writer Sarah Matusek contributed to this report from Parker, Colorado.