• California winds ease: Flame-fanning weather in Southern California has quieted as firefighters report significant gains against the two massive wildfires burning near Los Angeles.

• Sudan draws U.S. sanctions: Washington will reportedly impose sanctions on the country’s leader, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, a week after imposing sanctions on Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commander of the Rapid Support Forces, a paramilitary group engaged in civil war.

• Rubio replacement in Senate: Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody will take Marco Rubio’s seat in the U.S. Senate, Gov. Ron DeSantis announces, making Ms. Moody just the second woman to represent Florida in the chamber.

• South Africa standoff ends: A monthslong stalemate between police and miners trapped while working illegally in an abandoned gold mine in South Africa ends after authorities cut off supplies.

• Satellite launch: Blue Origin launches its new rocket, sending up a prototype satellite to orbit Earth. With funding by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, the 320-foot rocket carried an experimental platform designed to host satellites or release them into their orbits.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Records matter more than rhetoric. That truism underlies two of our stories today: Linda Feldmann’s clear-eyed review of President Joe Biden’s legacy and Ned Temko’s dispassionate look at President-elect Donald Trump’s potential for resolving situations in some of the thorniest global trouble spots – based on evidence from his first-term efforts.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

News briefs

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 6 min. read )

Word that Israel and Hamas had agreed to a Gaza ceasefire and hostage release deal was greeted with relief and some celebrations. But Israelis and Palestinians have been disappointed before; joy over the fragile deal was muted.

( 6 min. read )

President Joe Biden is leaving office after a single term that many Americans regard as unsuccessful. But history suggests his accomplishments could be viewed more favorably over time.

Patterns

( 4 min. read )

Donald Trump has ambitious diplomatic goals for hot spots around the world, and he prides himself on his skill at making deals. But agreements with China, Russia, and Iran would be a tall order.

( 5 min. read )

President-elect Donald Trump says he’ll halt refugee resettlement when he returns to office. Refugee groups are taking action on lessons learned during Mr. Trump’s first term, when the program was significantly downsized.

( 6 min. read )

The prospect of a former president facing four separate criminal trials divided Americans – but has now evaporated. Beyond the details of the cases themselves, America is opening a new chapter on questions of presidential accountability.

( 3 min. read )

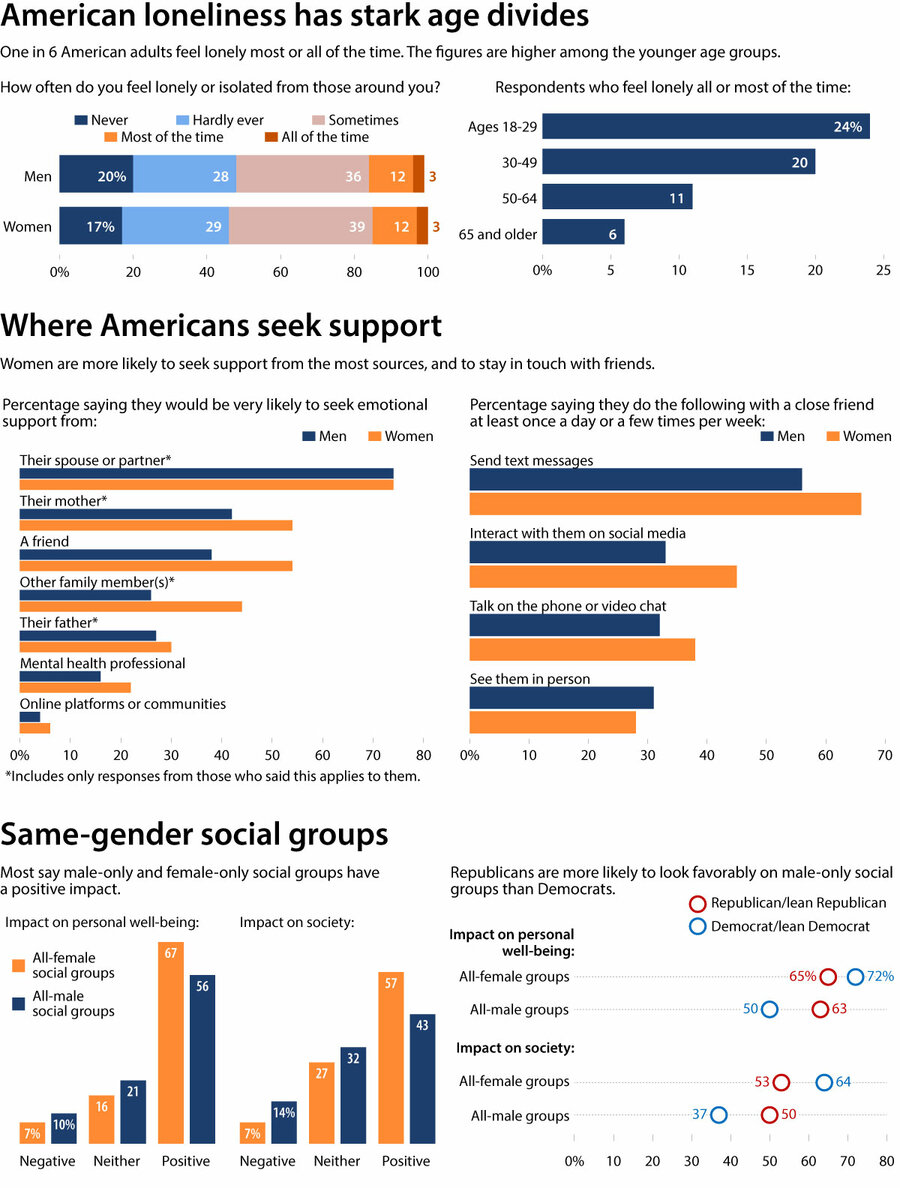

Americans now spend more time alone. Is isolation the price of technological convenience?

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

The Taliban have imposed 127 restrictions on women since returning to power in Afghanistan in 2021, according to a running tally by the United States Institute of Peace. Public stoning of women is allowed. Their voices may not be heard in public.

That hard-line approach to governing may be getting harder to maintain. New overtures from neighboring countries offer the Taliban a potential break from international isolation (no country has recognized the group’s government). But in a region learning to embrace equality for women, engagement has conditions.

Earlier Thursday, Taliban representatives met with Qatari officials in Doha seeking more opportunities for Afghan migrant workers. The meeting was co-chaired by Sheikha Najwa bint Abdulrahman Al Thani. As the host country’s deputy minister of labor, she has been a strong advocate of empowering women in the workforce.

India signaled an even bigger opening when its foreign secretary, Vikram Misri, met with his Taliban counterpart in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, last week in the highest-level talks between the two sides in three years. For India, Afghanistan represents potential trade and security benefits as it competes with China for regional dominance and seeks to isolate Pakistan.

But in a sign of the potential risks for India in legitimizing the Taliban, the talks included softer issues such as cricket, visas for health care and education, and humanitarian aid for Afghan refugees.

“Some engagement with the international community might pressurise the government to improve its behaviour,” Jayant Prasad, former Indian ambassador to Afghanistan, told the BBC. The Taliban “know that will only happen after internal reforms” such as restoring rights to education and careers for women and girls.

The most important shift, however, may be coming from within the Taliban themselves. Amid worsening economic conditions, rifts are widening between the old guard and a younger generation. In one sign that the group sees a need to accommodate more voices, it issued a directive Thursday that no official could hold more than one government job at a time.

The Taliban are “feeling the pressure from the Afghan people, who are asking for services and jobs amid a collapsing economy and limited international assistance,” wrote Lakshmi Venugopal Menon, then a doctoral student at Qatar University, in Al Jazeera last September. Yet atttempts by moderates to “seek engagement, more aid and investment are being undermined by [hard-liners] doubling down on policies like education bans on girls and women.”

A report released Thursday offered a rare insight into efforts by Afghan women to persist in seeking equality amid such harsh measures. “Women-led organizations [have] found new platforms for communication and outreach ... to actively participate in advocacy, establishing themselves as credible sources of support for women and girls,” stated the Women and Children Legal Research Foundation, a Kabul-based organization.

They are being heard. The regional shifts opening a path for the Taliban out of isolation include a recognition that equality is an essential condition of shared security and economic prosperity. As Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has noted, “We cannot achieve success if 50 per cent of our population being women are locked at home.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

In obeying God’s health-giving messages, we discover that God’s help is powerful and effective.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for spending part of your day with the Monitor. In our Friday Daily, along with the news, we’ll have Peter Rainer’s review of “I’m Still Here,” inspired by true events from military-dictatorship-era Brazil in the 1970s, along with a photo essay from the Sahara, where a revival of traditional mud-brick construction is emerging as a form of climate adaptation.