The Olympic spirit: 7 athletes share tales of grit and sacrifice

Loading...

For those named competitors in the world’s most ancient athletic competition, there are no days off. Finished the day’s laps? Swim another. Cleared enough hurdles? Jump a few more. Lifted a personal best? Add more weight.

Take any of the 40 sporting competitions that will be held at the Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games. The best in the world had to train and practice their skills again and again to get here. For some athletes, their sport isn’t popular enough to allow them to compete year-round and earn money. But they train anyway during the four-year gap between Olympics. Some say 10,000 hours is the minimum a person must put in to become an expert. But for an athlete to be considered one of the best in the world, that might be on the low end.

What is more important, the journey or the destination? Not every Olympian will win a medal, but simply making it to the Games is among the rarest of accomplishments. It is a reminder of the awe-inspiring grit that it takes to persevere and reach such a monumental goal. It’s an honor that can’t be bought or bartered for. It is earned, and millions will share the experience, watching on television screens around the globe.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onOlympic glory isn’t just about medals. For these athletes, the honor and joy of competition are their own triumphs. Still, gold would be good, too.

“We often talk about sport as an incredible unifier across boundaries that sort of penetrates language barriers, that penetrates cultural barriers,” says Sarah Hirshland, CEO of the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee. “It’s an opportunity for us to celebrate in that place in that way, at a moment in time where we haven’t had a lot of that lately, and we don’t see a lot of it in our day-to-day lives.”

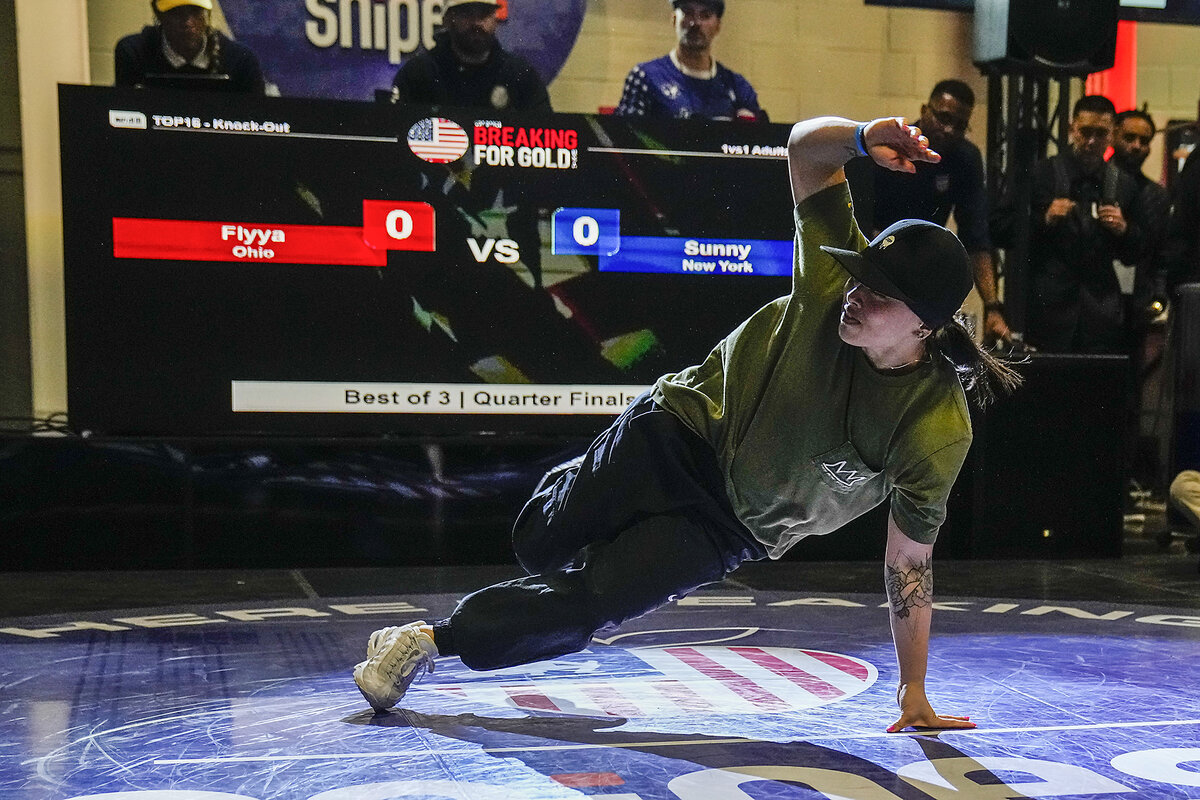

This year some sports, like breaking, are new. The hip-hop dance style started on the streets of New York City with kids throwing down backspins and propeller kicks on makeshift cardboard dance floors. It evolved into a global phenomenon and now an Olympic sport. Some relatively new sports, like women’s boxing, may not be featured in Los Angeles in 2028. So for these athletes, it is critical to make the world want more.

Here are just a few stories of the dedication and sacrifice each Olympic athlete puts in to give us this shared experience, which in some form dates back millennia. Let the Games begin.

Morelle McCane: Boxing, USA

If you find yourself around Team USA boxing sensation Morelle McCane long enough, she just might sing for you.

She’s laughing with a group of reporters a few months before the Olympic opening ceremony. “Listen, I’m every woman,” she says gleefully. “It’s all in me.” As the reporters scribble her words, she serenades them with Chaka Khan’s famous 1978 hit, “I’m Every Woman.” “That is my jam,” she says about the song. It’s a positive affirmation that she uses to motivate herself, she says. As a boxer, she’s always looking for something to motivate and inspire her – like a superhero’s special ability to confront any nemesis.

She found the sport of boxing by happenstance. Her niece, Anarie, was being bullied in elementary school, so one of her family members signed her up for boxing classes to learn how to defend herself. But Ms. McCane’s niece was uncomfortable attending classes until her aunt agreed to go with her.

“I went with her, and I started doing it as a workout,” she says. “But after that, I was just like, ‘I love it!’” She laughs. “I got into it by accident, but I’m a strong believer in God, and God doesn’t make any mistakes.”

It turned out Ms. McCane, who grew up in the Glenville neighborhood of Cleveland, was very talented. An orthodox right-handed amateur, she went from using boxing as a workout to winning four Golden Gloves championships. She’s won a gold medal and two silver medals at international competitions, including a silver at the 2023 Pan American Games in Santiago, Chile. She plans to turn pro in the future.

When she was in high school, NBA All-Star, Olympian, and Cleveland legend LeBron James spoke to the students. It was a moment that particularly inspired her, she says. The world-famous athlete’s agent, Rich Paul, is from her neighborhood. Graduates of Glenville High School include the comedian Steve Harvey as well as the creators of the comic superhero Superman, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel.

“I just got a lot of good energy around me,” Ms. McCane says. “Just knowing that these people walked and did all this, and are from the same neighborhood that I’m from, and now I have people saying that about me. I’m just honored.”

She became one of the toughest, hardest-to-beat fighters in the country. But her victories in the boxing ring coincided with losses in her personal life. Shortly after she became an amateur fighter, her younger brother, Gregory, drowned in a lake. She keeps a framed picture of him as she travels around the world. She’s the seventh of eight children in her tribe, and each of them and her mother are hoping to see her represent her country in Paris this summer.

“My whole family is trying to rent a boat,” she says with a laugh. “They don’t care. They are trying to make it.” The Olympian started a GoFundMe page to raise the funds necessary to bring them all to Paris. There might not be a next time.

Women’s boxing has been scratched from the 2028 Olympics in the United States. That could change. Ms. McCane hopes she can help generate enough interest in her sport so it can be reinstated.

She’s very motivated to compete. At the PanAm Games in Santiago, she won the silver medal even though she was boxing with a fractured left thumb. She lost the gold medal match to a woman from Brazil, and she hasn’t forgotten about it. “If there is a rematch, she better pray. She better run,” Ms. McCane says with a playful laugh.

– Ira Porter / Staff writer

Lauritta Onye: Para throw, shot put, Nigeria

Growing up in a village in southern Nigeria, Lauritta Onye was sure she was going to be a star someday. She imagined herself on red carpets and movie posters, a leading lady in her country’s globally renowned film industry, known as “Nollywood.”

“I wanted to fly in a plane; I wanted to see the world,” she also says. “I had the dream to do something great.”

Three decades later, Ms. Onye has indeed become something of a star – though not quite in the way she dreamed. At the Paris Paralympics, she will compete in the para throw competition in shot put. She’s the defending Olympic bronze medalist and a former world record holder in the F40 category, which is for women who stand under 4 feet, 1 inch (125 centimeters).

Ms. Onye was introduced to shot put in her early 20s, after she moved to Nigeria’s largest city, Lagos, to pursue her dream to be an actor. It turned out she was really, really good at heaving a shot put, however.

“I realized the talent I have for this thing, it’s big,” she says.

By 2011, she was representing her country at international competitions. But she had no sponsors, and she struggled to find the resources to train at an elite level. “I was sometimes training [while] hungry,” she remembers. “I once fainted on the track.”

Still, she kept setting and then breaking her own F40 world record. At the 2016 Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro, she shattered it in particularly dramatic fashion. A video of her cartwheeling and dancing across the track in celebration went viral. “I felt at that moment that all my struggles had been worth it,” she says.

But her success didn’t translate to more funding or better training facilities, Ms. Onye says. Instead, she was kept going by the fierce support of her coach, Patrick Anaeto. “He was the one who first told me, ‘You have the fire in you to be great,’” she says. When she didn’t have bus fare to come to training, she says, he gave her the money. When she arrived with an empty stomach, he took her to lunch.

As she became a successful athlete, she was also able to fulfill her childhood dream. She landed a starring role in the 2015 Nollywood film “Lords of Money.” But her acting career remains more of a side gig now. She continues to train hard to maintain her skills as a world-class para shot-putter.

Last year, Mr. Anaeto died suddenly when he was helping other athletes train in South Africa. Ms. Onye reeled with grief at a moment she was training to get ready for the Olympics. “I miss him all the time,” she says. “He was everything to me.”

Now she is determined to make him proud in Paris. “What keeps me going is, I love this job,” she says. “And I love being the best.”

– Ryan Lenora Brown / Special correspondent

Uriel Canjura: Badminton, El Salvador

Seven years before Uriel Canjura qualified for the 2024 Olympics, the Salvadoran Badminton Federation had already set its sights on the athlete. He was a 17-year-old prodigy then, but the federation was concerned about one thing: his height.

“Experts came by and they told us he had a desirable skill set and agility, but told us we could have some trouble because of his height,” says Armando Bruni, president of the federation. “He didn’t have the best nutrition as a child, and his height, at 5-foot-5, wasn’t the best.”

Mr. Canjura was born and raised in San Antonio del Monte, Suchitoto, a hamlet 30 miles north of San Salvador. Like many children in El Salvador, he played soccer, the national sport. But Antonio Ardón, his stepfather, was the administrative manager of the country’s recently established badminton governing body, and he brought home some rackets and a shuttlecock. There was, of course, no badminton court in this rural town, so Mr. Ardón measured a dirt court and improvised a net out of sacks. That’s how the 2024 Olympian, then just a barefoot kid, learned the sport, which can be traced back to ancient Greece, China, and India.

In its history, El Salvador has sent only 135 athletes to the Olympic Games. (In 2024, the U.S. will send more than 500.) In Paris, Mr. Canjura will be one of eight Salvadoran athletes competing for their country, and the first ever to compete in badminton. He will also be one of the country’s flag bearers in the opening ceremony. El Salvador has never won an Olympic medal.

Mr. Bruni, who also heads the Salvadoran Olympic Committee, says they decided to focus on the talented young badmintonist early on, paying for his education at a private school close to the training center in San Salvador.

Mr. Canjura became so good that no one could compete with him in any meaningful way, not even his trainers. So the federation sent him to Spain, where he plays in that country’s national badminton league for the team from Oviedo. He’s also trained in Denmark, the Czech Republic, and Mexico, where he is currently preparing for the Olympics.

“It’s the biggest achievement of my career,” Mr. Canjura said after he won a spot to compete in Paris. “I thought about my mom, who supported me throughout. She let me stay playing badminton even after I flunked a year in school.”

Badminton is a fast-moving racket sport played in a relatively small 44-by-20-foot court. Tall players can smash the “birdie” at speeds of up to 250 mph, according to the Olympic website. Feathery-touched drop shots can be just as devastating. Mr. Canjura compensates for his lack of height with optimal physical conditioning and a superb defensive play style that allows him to extend rallies and force errors.

Mr. Bruni, who has two shuttlecocks on his desk and displays Mr. Canjura’s Olympic uniform in his office, is very enthusiastic about the talented badminton player’s prospects – as well as El Salvador’s other three Olympians. “Our athletes are in good shape to deliver results our Olympic sports haven’t had so far,” he says.

– Nelson Rauda Zablah / Special contributor

Bobby Body: Para powerlifting, USA

Paris para powerlifter Bobby Body has the perfect name for a man who can bench-press more than 500 pounds. And yes, that’s the real name of the 2024 Olympian. His birth certificate says so.

Bobby isn’t a hypocorism for Robert. And Body has a soft ‘o.’ Add a definite article between them and his birth name could be a cool stage name in professional wrestling. His biceps might even challenge 1980s pro wrestling sensation Hulk Hogan and his 24-inch pythons.

But once a soldier, always a soldier. A U.S. Marines combat veteran, Mr. Body was in a Humvee when it hit a roadside bomb. His left shoulder and leg were badly injured. Doctors performed numerous surgeries to save his leg, but they eventually had to amputate below the knee.

“I was very frustrated with not being able to run again, jump again, and stuff like that,” Mr. Body says.

His childhood was difficult. His mother left when he was 5 years old, and his father went to prison when he was 10. So both Mr. Body and his sister spent much of their childhoods in an orphanage. Later, he spent time without a place to live in California.

His long recovery and rehabilitation with the Veterans Health Administration, however, changed his life in ways he never expected.

“They were like, ‘Go to the gym and let out some of that aggression,’” he says. “While I was in the gym I was bench-pressing one day, and the owner of the gym says, ‘Hey, you’re pretty strong for someone that’s disabled. Have you ever considered powerlifting?’”

Mr. Body was skeptical. Lifting weights was just something he did to keep in shape and to distract himself from all the negative things that happened in his life. He never imagined he could compete as an athlete. But once he started entering competitions, he was energized.

“This is the coolest thing that I’ve seen,” he remembers saying. Then in 2015, a manager for the U.S. Paralympic team reached out, just to gauge his interest in international competitions. He said he wasn’t interested. But the team persisted, and in 2019, he finally said yes.

“I told them I would do it, but then COVID hit and everything went down.”

Para powerlifting includes just one kind of lift: a bench press in which competitors must keep their legs and heels on the bench, not on the floor. Mr. Body learned the proper techniques, and found he was quite good.

At the 2023 Parapan American Games in Santiago, Chile, Mr. Body was about to take his third lift when he told someone on his team that he wanted to shoot for 228 kilograms, or just over 500 pounds. He pressed it, winning the United States’ first para powerlifting gold medal.

After his historic victory, the veteran wept as they raised the U.S. flag to the national anthem – which he is determined to experience again in Paris.

“Of course, when they waved the American flag, I didn’t even see what happened because I was just bawling.”

– Ira Porter / Staff writer

Nigara Shaheen: Judo, Refugee Olympic Team

Nigara Shaheen knew the moment she stepped onto a judo mat as a young girl that she wanted to represent Afghanistan in the Olympics.

But she was an 11-year-old refugee living with her family in Pakistan at the time, and she failed to comprehend how hard it would be to break gender barriers in her region. It was difficult to find a sense of belonging as she moved from country to country, and she had to rebuild relationships with coaches each time. These were enormous obstacles to being just a decent judoka, let alone a world-class competitor.

Even so, she had enough talent to compete at international tournaments, qualifying as a member of the International Judo Federation Refugee Team. She competed in the 2017 Asian Judo Championships and in numerous Judo Grand Slam events, and qualified for the 2020 Olympics. But she reached a low point while training in Russia during the pandemic. Her mother showed her an old picture of her competing as a child, which she had hung on their cupboard in their home in Peshawar, Pakistan. The young Ms. Shaheen had drawn the five-ringed symbol of the Olympic Games on it. Now that dream seemed in peril.

But the athlete, who was also studying international development at the university in Yekaterinburg, Russia, at the time, embraced the principles she learned from competing in judo: get up again, find confidence, forge forward. “If you want to be a judoka, you need to learn how to fall,” she says. “And that’s how life is, right?”

Ms. Shaheen was able to make her delayed Olympic debut in Tokyo in 2021, competing as a member of the Refugee Olympic Team. But her debut didn’t go as planned. She couldn’t train efficiently during the lockdown. Her roommate would leave their dorm room for a few hours each day so Ms. Shaheen could throw a mat on the floor and practice falling. In her first match in Tokyo, she injured her shoulder and needed surgery in Japan.

This summer, the Afghan judoka has another opportunity to compete on the world’s largest sports stage in Paris as one of the 36 athletes competing as members of this year’s Refugee Olympic Team, which represents the world’s displaced populations.

As a refugee, Ms. Shaheen has seen dramatic chapters in life. Her family fled civil war in 1994 when she was 6 months old, the youngest of four siblings. Nearly two decades later, she returned to Afghanistan to attend American University in Kabul. Her classes in gender and debate awakened a sense of injustice she had felt since she was a child. “I’ve been a feminist since sixth grade,” Ms. Shaheen says.

But that was a fraught time. She was the only woman practicing in a male-dominated sport that requires close physical contact. She was threatened and bullied, and attacked on social media, and her parents had to accompany her to practices.

When the Taliban captured Kabul in 2021, the family was forced to flee, making them refugees for a second time. Today her family is dispersed across three continents.

Ms. Shaheen now lives in Canada, near Toronto, where she trains 4 1/2 hours a day. She also finished a postgraduate program in international development at nearby Centennial College. After the Olympics, she aspires to work with refugees through sport. She also tutors schoolchildren in Afghanistan online from her home in Canada.

Amid all of her challenges, it’s been most difficult to live far from her family. They grew up in a one-room house in Peshawar “where we created so many memories together,” she says. Amid visa challenges and the upheavals of uprooting, none of her family members are able to travel to Paris to watch her in person. And while she’s not representing Afghanistan, she is part of a team that represents 100 million displaced people around the world. For that, she feels a deep responsibility to share her story on the platform she’s been given.

“I’m a feminist, I’m a refugee, and I’m from Afghanistan,” she says.

– Sara Miller Llana / Staff writer

Shannon Westlake: 50 m rifle 3 positions, Canada

Far from the glare of the spotlights and blinking ad campaigns and Olympic celebritydom, Shannon Westlake lives quietly in Utopia, Ontario.

A mother and full-time project manager, the Canadian Olympian is making her debut in Paris in the 50m rifle 3 positions competition, but the long journey to reach this accomplishment has been anything but glamorous, she says. Her motto along the way: “Chop wood, carry water.”

“I’m probably one of the most boring people you will ever meet,” she says in an interview. But in many ways, it’s that sense of humility and understatedness that makes for excellence when it comes to her sport. And that she has been honing her entire life.

It has been 24 years, an entire generation, since Canada last had an entry in any women’s rifle event at the Olympic Games. Ms. Westlake won a bronze at the 2023 Pan American Games in Santiago, Chile. She then claimed her spot on the Canadian Olympic team at her sport’s trials in May. That would have seemed “far-fetched” when she started out, she says.

She began shooting at age 12 as part of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets. As a teen, in fact, she wanted to join the military. (She’s a part-time reservist today.) But she loved the sport from the start, and worked tirelessly to get better. Now in her late 30s, she has overcome setbacks that almost made this moment impossible, including an injury during a pickup volleyball game in which she tore three ligaments. One specialist told her she’d never shoot kneeling again – which should have put an end to her Olympic dream. In her event, a shooter must compete in prone, kneeling, and standing positions. “I said, ‘That’s not gonna happen,’” she says. Her routine is strict. Through workouts, training, and meditation, discipline has been foundational to her goals.

“I don’t have a lot of friends. There’s no social life,” she says. But it’s her family members who have made the most sacrifices. “They’re the ones that have missed out more than anything, because they don’t really care that I’m an athlete. These are my goals, not theirs.”

Her sport is misunderstood, she says. Some just think the rifle is doing the work, or that it’s a matter of simply standing still and firing. They don’t see how much the rifle weighs. They don’t see the tedium, the days she spends holding position for an hour at a time to build muscle memory. They don’t see the visualization at work to calm the heart rate, even amid cheering and other distractions. They don’t realize how hard it is to tamp down the adrenaline surge that is so crucial in other sports. Her success is all about focusing inward, shutting out everything else. “It’s all about being totally present for me.”

That’s been harder under the spotlight as she prepares to represent Canada at the Olympics. Her son keeps her humble, though, she says. Her family will be in Paris, and sometimes he’s impressed that he’ll see his mother at the Chateauroux Shooting Centre south of Paris. “But I think he’s more excited that he gets to go to France for a few days.”

– Sara Miller Llana / Staff writer

Sunny Choi: Breakdancing, USA

When Grace “Sunny” Choi’s parents sent her off to the Ivy League, they expected her to learn the ins and outs of business at The Wharton School. So Ms. Choi got the world-class education they wanted her to get. But it was what she learned in an extracurricular dance class that pays her bills now.

“I got to college, and I was pretty lost. I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” she says. “I was out late one night, and there was some people dancing on campus, and I was like, ‘Oh, that looks fun!’”

So she went to a breakdance class off campus. “Initially I just watched everyone else dance, because I just didn’t have the guts to go out there and do it,” she says. “But over time, I really fell in love with exploring my body’s physical limits and artistic expression.” She also began to “battle,” a competitive tradition in breaking that goes back to the origins of hip-hop.

In an attempt to attract more young viewers and ticket buyers, the International Olympic Committee added competitive breaking to this year’s Paris Games. A part of the traditions created by Black youth in the streets of New York City in the 1970s, “break dancing” began when “B-boys” and “B-girls” from the Bronx would go all out during a song’s “breakdown.” It evolved into a dance style that required athleticism and gymnastic-like grace, as well as creativity and style within the beats and rhythms of hip-hop. Informal battles added a competitive element that pushed breakers to test their own physical limits. Decades later, these became organized competitions with governing bodies. Now it’s an Olympic sport, and competitors are still called B-boys and B-girls.

Despite her early reticence, Ms. Choi turned out to be a natural. After college, she entered corporate America, eventually earning the title director of creative operations for Estée Lauder. She trained and competed in breaking competitions on her own time. As her side hobby became an Olympic sport, however, she left her position earlier this year to focus full time on her breaking.

She has competed against some of the best B-girls in the world, earning a gold medal in the 2023 Pan American Games in Santiago, Chile, when the event debuted last year. She also won a silver medal at the 2022 World Games in Birmingham, Alabama. B-boys and B-girls mostly use mononyms or stage names in competitions, and Ms. Choi competes as “Sunny.”

She always dreamed of performing at the Olympics – but as a gymnast. “I watched the ’92 Games when I was 3,” she says. “I bugged my mom for a whole month to put me in gymnastics.” So her mother signed her up for classes at a local YMCA. “I was dressed in a tutu, and the whole car ride there, I was like, ‘Am I going to win gold?’” she says with a laugh.

Despite her accomplishments, she still battles her own self-doubt.

“My whole life, I hadn’t allowed myself to do things because I was scared of failing,” Ms. Choi says. “I had always done the safe route, and I finally decided that I’m going to give up this job. I’m going to go out for the team and see what happens, and here I am.”

– Ira Porter / Staff writer