Eagle Pass, Texas, once boiled with border crossings. Now it’s quiet.

Loading...

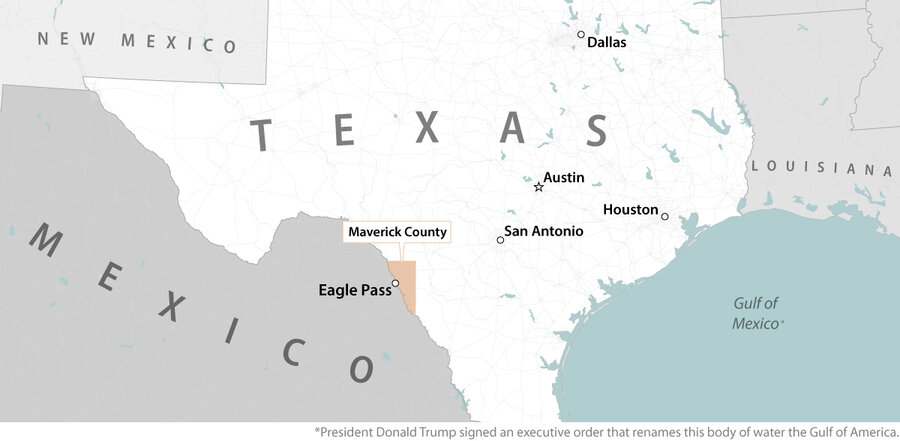

| Maverick County, Texas

On a bumpy dirt-road drive through a watermelon farm, Kate Hobbs points out the flood plain. There’s a 1 in 100 chance of a major flood each year, she says.

Hard rains haven’t come to this farm near Normandy, Texas, but people have – thousands in recent years. The flood plain is where her husband had just arrived before calling her, upset, on Mother’s Day 2021.

She was cooking at the house. He told her he’d found five little girls, stranded. Ms. Hobbs, who came to see for herself, recalls how one, a baby, crawled in the dirt with her diapers gone.

Why We Wrote This

Texas provided a border-enforcement blueprint for President Donald Trump. Now, people in the Eagle Pass area, which was once an immigration epicenter, live with a new, quieter reality.

Ms. Hobbs was angered by whatever led to the abandonment of those girls, who, authorities later said, were from Honduras and Guatemala. But she was also disturbed by the many more unauthorized immigrants she watched illegally enter the United States during the Biden administration. They trampled irrigation lines on the border farm her family manages, and left trash and human waste, she says. She felt afraid to venture far from her house.

“This was probably the most inhumane way to bring people into America. ... They were used; they have been victimized,” she says, driving past drought-parched fields.

After reaching record highs during the Biden administration, those crossings have plummeted in the area – as they have across the country – since President Donald Trump’s inauguration. Border Patrol encounters at the southern border, a proxy for illegal crossings, were down 93% in April compared with the same month last year.

By the time he left office, President Joe Biden had secured more enforcement help from Mexico and limited access to asylum, and encounters had declined. But illegal crossings have fallen much further in President Trump’s second term, to their lowest level in at least 25 years. Mr. Trump’s supporters say Mr. Biden could have brought numbers down sooner if he’d pursued similar policies.

Since taking office Jan. 20, Mr. Trump has declared a national emergency at the southern border and surged troops. He’s escalated a controversial deportation campaign, drawing lawsuits and due process concerns. Nationally, 56% of the U.S. public approves of Mr. Trump’s handling of border security, while 44% disapproves, according to a Marquette Law School poll this month. Republicans are overwhelmingly supportive, while a majority of Democrats and independents disapprove of his actions.

“The border has never been as secure as it is right now under President Trump,” says Ms. Hobbs. Relieved, she now sleeps with one gun instead of two.

People in Maverick County, where Mr. Trump made his biggest gain across all Southwest border counties in November, have seen a dramatic difference over the past several months. They’ve watched the federal government’s immigration crackdown bolster Texas’ efforts to hold the line. State and federal troops have combined their patrols to create a new border reality here.

A rust-color border wall is rising on the watermelon farm, paid for by the state, a reminder of the logistical and ideological partnership between two levels of Republican-led government.

Texas provided a border-enforcement blueprint for President Trump. Under Gov. Greg Abbott, the Lone Star State reports spending more than $11 billion on securing its border, which it began militarizing before Mr. Trump created “national defense areas” of his own. The state’s former “border czar” now leads the U.S. Border Patrol. And Texas officials ramped up cries of a border “invasion” before the White House used the term to justify deportations, curtailed by courts, to Salvadoran prison cells.

How a crackdown escalated

South of Ms. Hobbs’ farm, down U.S. Highway 277 toward Eagle Pass, dust-encrusted clothes and water bottles lie scattered among prickly pear cactus. They’re what’s left of what Luis Valderrama describes as his time spent helping the Border Patrol round up unauthorized immigrants on his property.

Now, he chuckles, “It’s kind of boring.” But he still keeps watch.

As an ex-Border Patrol agent-turned-rancher, Mr. Valderrama welcomes the drop in crossings.

“They were cutting my fence four times a day, these aliens,” he says. “Holes big enough for cows to get up on the highway.”

While the state has installed fencing on his property, and will build a section of border wall, he says the barriers aren’t ideal. They stop some but not all migration, and are no replacement for more agents, he says. The barriers also limit his own access to the land.

Statewide, over 60 miles of border wall have been built since 2021, with more planned, according to the Texas Facilities Commission. The Texas-Mexico border is over 1,200 miles long.

Texas politicians are requesting reimbursement from Congress for their border security spending. When the governor launched Operation Lone Star in March 2021, he pitched it as an intervention – against former President Biden’s perceived refusal to secure the border.

Border Patrol encounters swelled to historic highs under President Biden along the southern border, cresting over 2 million for two consecutive years. Images from cities like New York and Denver, overwhelmed by trying to provide services for unauthorized immigrants, including many seeking asylum, turned immigration into a national political liability for the president.

In November, Mr. Trump flipped Maverick County from blue to red. He earned 59% of votes here – up 14 percentage points from 2020.

In addition to immigration, issues like economics moved voters here, says Sylvia Gonzalez-Gorman, associate professor of political science at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Also, “The Democratic Party did not have a good, solid ground game,” she says.

Still, Eagle Pass, a bilingual city where family and business ties span both sides of the border, became internationally known as an epicenter of illegal migration under the prior administration. Now all is quiet.

The county of roughly 60,000, around half of whom live in Eagle Pass, saw thousands of men, women, and children trudge through the Rio Grande to reach its U.S. side. Locals were irked by the temporary closure of one of the city’s international bridges in late 2023, as U.S. Customs and Border Protection redirected personnel to process migrants. Early the next year, Texas ordered state forces to shut down public access to Shelby Park and its boat ramp, on the water’s edge. The state has strung orange buoys as a further deterrent along the river, whose middle marks the international boundary.

Meanwhile, the Border Patrol has deepened its partnership with Texas troops. Since February, the Del Rio Sector has deputized over 1,000 Texas Army National Guard members to act as Border Patrol agents, according to a Customs and Border Protection spokesperson, citing a provision of immigration law.

Beyond helping train those guard members, who ride along in Border Patrol vehicles, agents conduct “mirror patrols” with counterparts in Mexico. Those are simultaneous operations on both sides of the border.

The Del Rio Sector, which reported 40,931 encounters in April 2022, reported 1,055 encounters last month.

Messaging was a big factor in the drop, says Oscar Salinas, patrol agent in charge of the Del Rio Station. Beyond “telling people that the border is closed,” he says, there is actually a “consequence being delivered.”

With fewer agents tied up with processing large groups, they’re freed up to patrol.

Whose “invasion”?

With an office a little more than a half-mile from the river, Pepe Aranda is an Eagle Pass booster. An image of a stern-eyed eagle watches from one of his walls. The real estate broker says the city’s new name recognition is good – even if born out of bad headlines.

The former mayor, raised here, saw Shelby Park turn into what he calls a “stage,” used to push a message about lack of border enforcement. Even Mr. Trump campaigned at the park last year.

“At that time we would say we were being invaded, but not by immigrants,” Mr. Aranda says. The incursion came from politicians, he clarifies, and National Guard members sent from other states. At the same time, he notes, their arrival stirred spending on things like local lodging and restaurants.

Still, unlawful crossings took their toll. More dangerous migration – through the river, on the outside of trains – meant more injuries and deaths. Those strained the city’s emergency services, causing delays in response and more overtime shifts, says Rodolfo Cardona, assistant fire chief. Last year, he told the Monitor that immigration-related emergencies put a mental health strain on staff.

Now, work is returning to normal, he says at his desk. “We don’t have the abundance of calls.”

While Mr. Cardona says immigrants traipsed through his own property, and stole shoes from his porch, he never felt his “home was being invaded.”

Others wish state funds spent on border security were apportioned elsewhere.

“The rate at which we’re just bleeding money is incredible,” says community organizer Amerika Garcia Grewal. Another $6.5 billion approved by the GOP-run state Legislature, for more border security, won’t go to schools, hospitals, or other local needs, she says. There are colonias, low-income housing developments, that lack running water, Ms. Garcia Grewal points out. Meanwhile, Texas put resources toward building Camp Eagle, a military base nearby, within a matter of months last year.

Down at the Rio Grande, the partially reopened Shelby Park is still edged with sharp, spiraled wire and shipping containers. A Texas Army National Guard member, with a rifle, patrols near a group gathered for a monthly border vigil. Ms. Garcia Grewal helps organize the event, which honors what she calls needless deaths in the county, including migrant drownings in the river.

There were no known deaths last month, says Pastor Javier Leyva. Just before sunset, he leads 10 people in Spanish-English prayers. The group holds hands, swaying as it sings.

The river, silver as the sun fades, ribbons by. On the other side, a figure – who it is exactly, is unclear – watches on.