In Jerusalem, national parks seen by Palestinians as a land grab

Loading...

| Jerusalem

An Israeli government plan to create a greenbelt around Jerusalem, preserving the ancient city's natural beauty and archaeological wealth, is fueling opposition among Palestinians and their supporters as the project moves into a critical stage.

Israel says the parks plan is necessary for the public's benefit. It also fits into Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat's vision for bolstering tourism in Jerusalem, which, despite its storied history, gets only a fraction of the visitors of Paris or New York.

But critics say the parks amount to a land grab that consolidates Israel's grip on disputed East Jerusalem. The territory was annexed by Israel after the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and declared part of its "eternal, undivided capital." But it is envisioned by Palestinians as the capital of their future state.

"People say, 'It's just a park,' but these parks change totally the political scope of Jerusalem and have a direct impact on the lives of Palestinians," says Hagit Ofran, who monitors Jewish settlements in Palestinian areas for the dovish Peace Now movement.

Efrat Cohen Bar, an architect at the progressive Israeli planning group Bimkom, which recently conducted a study of national parks in East Jerusalem, terms them "green settlements," which have the same effect of keeping Palestinians off the land and expanding Israeli control. Israel denies that as a motive behind the project.

The battle for East Jerusalem

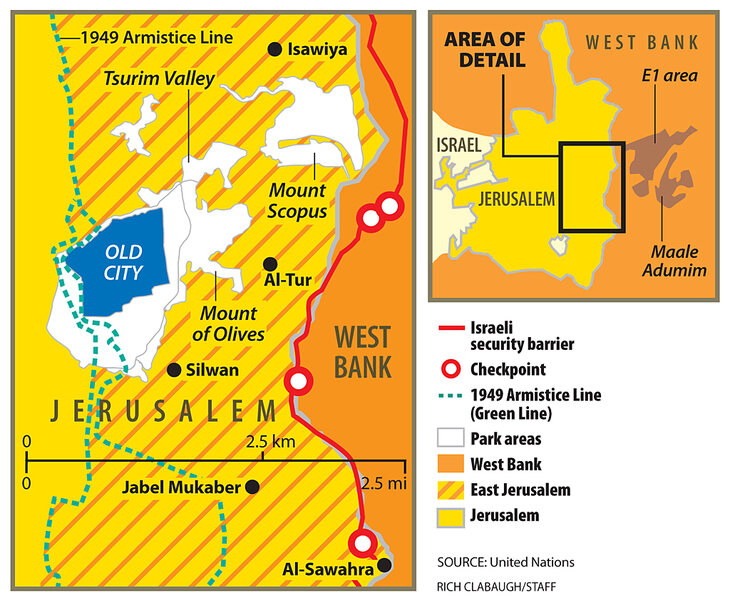

The national parks strike at the heart of the battle over East Jerusalem because they are on or near territory with nationalistic, religious, or strategic resonance. Together, they could link and expand areas under Jewish control, from the old city through the heart of East Jerusalem to the West Bank settlement of Maale Adumim.

The next phase of the parks plan would turn East Jerusalem's largest remaining open area into Mount Scopus Slopes National Park, overriding Palestinian objections that the land is vital to relieve a housing crunch. It is to be created on what residents say is the only land available for the expansion of the crowded Palestinian neighborhood of Isawiya.

"This park will choke the people of Isawiya into a given area and prevent them from having a natural life," says Isawiya leader Darwish Darwish. "It prevents any development and progress." Isawiya's 15,000 residents currently live on 150 acres – an area smaller than that of the planned park. Some 112.5 acres owned by Isawiya residents and 75 acres owned by residents of nearby Al-Tur are slated to become part of the park without any compensation to the owners, who would retain ownership.

Spearheading the national park drive is Evyatar Cohen, head of the Jerusalem district in the National Parks Authority and a former staffer for Elad, a hard-line settler group. The NPA, however, dismisses charges that the park is driven by any political motive. "The National Parks Authority is not a political body and its only interest is preserving nature and landscape values," says spokeswoman Osnat Eitan.

She stresses that "the importance of the area stems from the view to the desert, the heritage valuables in the area and the desert vegetation there despite many years of neglect. All the other eastern slopes of the mountain have undergone urban development, thus the importance of preserving this as an open area and in planning it as a national park."

The Jerusalem municipality, which is strongly backing the project, says the area of the park has "high archaeological importance," with sites dating back two millenniums. But Emek Shaveh, a group of dovish Israeli archaeologists, disputes that and counters that archaeology is being misused to boost Israeli claims in the larger battle for East Jerusalem.

Ancient monasteries and burial caves

When archaeological finds of similar worth were made in areas earmarked for Jewish neighborhoods, development proceeded and there was no declaration of the area as a national park, Emek Shaveh wrote in a recent report.

By local standards, there is nothing extraordinary in the Mount Scopus park area or in a neighboring swath of East Jerusalem, the Tsurim Valley, that was turned into a national park, the group says. "Ancient monasteries, burial caves, and industrial and agricultural facilities have been found in almost every neighborhood and settlement built in and around Jerusalem in the last 40 years," Emek Shaveh noted.

Emek Shaveh, joined by Peace Now, says the real reason the park is being built is strategic: to create Israeli contiguity between the old city and the highly sensitive area known as E1 on the outskirts of Maale Adumim, connecting the two via the Tsurim Valley park.

"There is no justification to have a park there," says Ms. Ofran. "Its only purpose is to connect the Holy Basin and E1." Critics of the project stress that if Israel one day builds settler housing in E1, Maale Adumim will be linked through the park to Jerusalem in a major boost for Israel in the battle over East Jerusalem and a setback to Palestinian hopes of having a viable future state.

But Jerusalem city councilor Yakir Segev, from Mayor Barkat's party, denies there are ulterior motives behind the Mount Scopus Park plan, which was posted for public objections in November and still needs to be passed by a committee affiliated with the Interior Ministry.

Mr. Segev, the former city councilor for Arab affairs, concedes Isawiya residents would be hurt by the park. But he denies the city has a policy of limiting Arab growth, saying new plans have been drawn up for expansion of two Palestinian neighborhoods, Jabel Mukaber and Arab al-Sawahra.

"There is no conspiracy here," Segev says. "And this [park] is not being done because the people being impacted are Arabs."