How Israeli-Palestinian battle for Jerusalem plays out in one neighborhood

Loading...

| Jerusalem

The second round of Israeli-Palestinian peace talks under way culminates tonight at Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s residence in Jerusalem, where Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas is expected to arrive for further face-to-face negotiations on core issues.

The meeting’s unusual location underscores Jerusalem’s emergence as not only the thorniest obstacle to Israeli-Palestinian peace but a defining battleground for sovereignty.

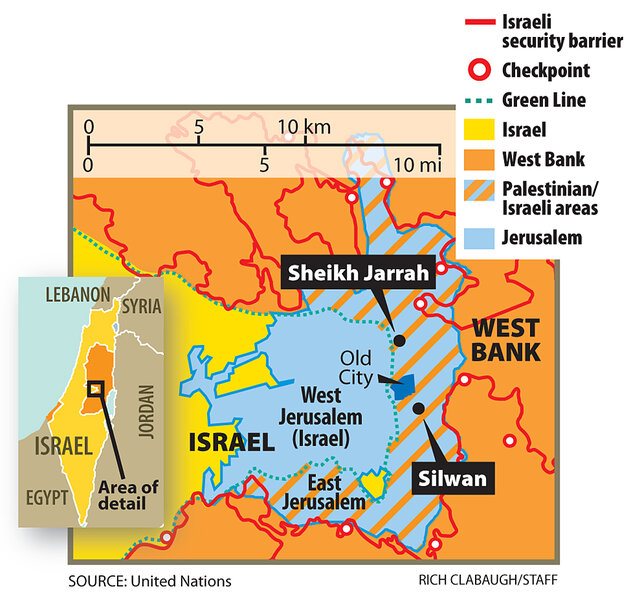

That fight is playing out – between Arab residents, religious Jews, and a municipality looking to revitalize its storied global brand – in the predominantly Arab neighborhood of Silwan. Nestled in the shadow of the Old City walls, Silwan serves as a microcosm of the broader tension between Israeli and Palestinian interests, in which every plot of land is seen not just as home, but a stake in one’s homeland.

Seeking to preserve home – and homeland

Fakhri Abu Diab shuffles out his gate to sweep stray trash and bits of rubble out of the narrow path to his home in the neighborhood.

But that’s about all the enthusiasm he can muster as he prepares to welcome guests. Why? Mr. Diab daily fears his home will be destroyed.

Once inside, he pulls out the Israeli demolition order that arrived on the eve of his daughter’s wedding last fall. Yes, he built without a permit, but he spent 10 years trying in vain to get one.

His home is now one of dozens affected by the Jerusalem municipality’s plans for an archaeological park. Jews and Christians believe the biblical King David once reigned here, and his son Solomon planted trees in the area, known today as King’s Garden.

“Who are more important? The families who live here now, or those 3,000 years ago?” asks Diab.

But for Israeli Jews, whose families endured millenniums of persecution, such efforts to “redeem” Jerusalem involve not just the preservation of holy sites, but the preservation of their nation.

“Jewish history, Jewish roots basically start from two places: the Temple Mount and the City of David,” says Daniel Luria, executive director of Ateret Cohanim, an organization that facilitates Jewish development in Jerusalem. “So when we talk about Jerusalem, we’re not talking about some outer neighborhood on the way to Tel Aviv. We’re talking about the places where prophets walked, where kings prayed, where basically the nation of Israel started.”

Why Silwan is on the front line

The stakes are high; US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has said these talks may be the last chance to agree on the two-state solution that many have long envisioned as the key to Middle East peace.

Israel never formally included East Jerusalem in the settlement freeze set to expire at the end of this month, a freeze Palestinians say must be extended to preserve the territory of their future state. The steady expansion of Jewish areas throughout East Jerusalem – through Israeli property laws, a Byzantine permitting process for new homes, and millions of dollars in state support – jeopardizes a key component of that statehood dream: a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem.

On the city’s flanks, numerous Jewish developments have populations in the tens of thousands. But it is the smaller enclaves in the highly sensitive areas around the Old City, such as Silwan, that have become the frontlines in this intensifying battle for sovereignty.

“There is a growing impression,” stated a 2009 report by Israeli human rights group Ir Amim, “that Silwan is the keystone to a sweeping and systematic process, whose aim is to gain control of the Palestinian territories that surround the Old City, to cut the Old City off from the urban fabric of East Jerusalem, and to connect it to Jewish settlement blocs in northeast Jerusalem and the E-1 area.”

A millionaire's plan to transform Jerusalem

Mayor Nir Barkat, a self-made millionaire who took office in 2008, sees Jerusalem’s future in much different terms. (Editor's note: The original version misstated Mr. Barkat's financial status.)

He’s not oblivious to the fact that Jerusalem is a relatively poor city losing 17,000 young Israelis per year to emigration, that the Jewish majority has slipped to 65 percent and will be lost altogether by 2035 if current trends prevail, and that Palestinian Jerusalemites, living in vastly inferior neighborhoods, feel increasingly alienated.

Mr. Barkat is also keenly aware that he is in charge of a metropolis that for centuries has been one of the most celebrated crossroads of humanity – a center of worship, culture, and commerce. And for him, that is the key to revitalizing the city and endearing it to a world more apt to criticize Jerusalem than to come taste its heavenly hummus.

The dazzle of New York, Paris, and Rome all draw more than 40 million visitors annually, notes Mr. Barkat’s foreign affairs aide, Stephan Miller, freshly returned from an August mayoral tour touting the city’s 3,000-year-old brand in North America.

“Cyprus, an island, gets 10 million per year,” he says, eyebrows jumping. “Jerusalem – a brand important to 3.4 billion people of faith around the world – gets on average 2 million.”

If Jerusalem can match Cyprus within a decade, they estimate it will create as many as 150,000 new jobs, roughly doubling the city’s job market.

The mayor, coming from the “win-win” world of hi-tech deals, envisions projects like the King’s Garden archaeological park as a way to not only woo tourists and make the city more attractive to young Israeli families, but also to bring better management to Arab areas such as Silwan.

Such projects would improve roads and sewage, and add new buildings such as a $10 million community center planned for Diab’s community.

The trickle-down effect, the municipality foresees, would open up more job opportunities for Arabs and give their children a better start in life through higher standards of living and improved schooling.

While roughly 2 in 3 Arab residents pay property taxes, the lack of building permits they obtain means that almost none pay the separate fees associated with buying and building homes – depriving their communities of a crucial cash pool for roads, schools, and other development, says Yakir Segev, the city councilor in charge of East Jerusalem.

Complicating the situation is the fact that Palestinian Jerusalemites refuse to vote or run for local government positions on principle.

“Cooperating with the municipality is sometimes perceived as accepting Israeli sovereignty,” says Mr. Segev. “We’re to blame to some extent for not overcoming the fact that these guys have chosen not to be represented, and then I think the [Arab] community can blame themselves for not cooperating and paying what they should have, and working with us to figure out how to help them.”

Silwan: Top priority in wider plan

The mayor has tackled Silwan as one of his first priorities in the wider effort to transform Jerusalem – using as a blueprint a massive rezoning plan he inherited, which calls for a green belt around much of the Old City.

But Palestinians in Silwan deeply resent what they see as an invasion of an area that they say has long been theirs, although satellite images gathered by the Jerusalem municipality show very little development until the 1990s.

As part of a compromise, the owners of 66 of the 88 Palestinian homes affected by the King's Garden plan will be allowed to apply retroactively for permits, though approval of the permits is not guaranteed.

They will also be allowed to build additional units intended to accommodate the residents of the remaining 22 homes – including Diab’s – that will be demolished to make room for the park.

But such proposals satisfy neither religious Jews, who seek a stricter interpretation of the law, nor residents.

“[Israel is] demolishing family, future, and any opportunity of peace between Israelis and Palestinians,” says Abu Diab. “I hope for me and my children’s sake a third intifada won’t happen. But if it does, it will be not just local, but regional as well. There are 20,000 Abu Diab families – in Amman, Saudi Arabia, US – and that’s just a small sample.”

But despite the intense emotions around the city's status, Ir Amim spokeswoman Orly Noy sees merit in tackling it head-on.

“We think that a solution is still possible in Jerusalem and in the conflict in general – and,” she adds, “that Jerusalem can, in fact, serve as a key for getting to this overall solution.”