The African cartoonists drawing themselves into the story

Loading...

| Johannesburg

Joëlle Épée Mandengue was raised on a steady diet of Disney princesses. As a child in Cameroon, whenever she got angry or overwhelmed, her parents knew the quickest way to calm her was to pop in a video and press play on the story of Snow White, Cinderella, or Beauty and the Beast.

And there was one princess who Ms. Épée Mandengue grew to admire above all others. Ariel, the Little Mermaid, struck her as a different kind of heroine – one “fighting to meet the expectations she had for her own life,” she says. “I like her because she was longing for a world she wasn’t a part of.”

Ms. Épée Mandengue knew that kind of longing well. Since the moment she’d first begun to watch Disney cartoons, she’d dreamed of creating something like them. But she quickly banished the thought from her head. It wasn’t practical, her parents said. And anyway, she knew who made the cartoons she loved. Most of them were men; most of them were white. When she imagined herself as an artist then, she felt like Ariel, trying to play a role she hadn’t been cast into.

Why We Wrote This

Comics are often treated as lighter fare. But like any other kind of storytelling, they help shape our ideas about what, and who, really matters.

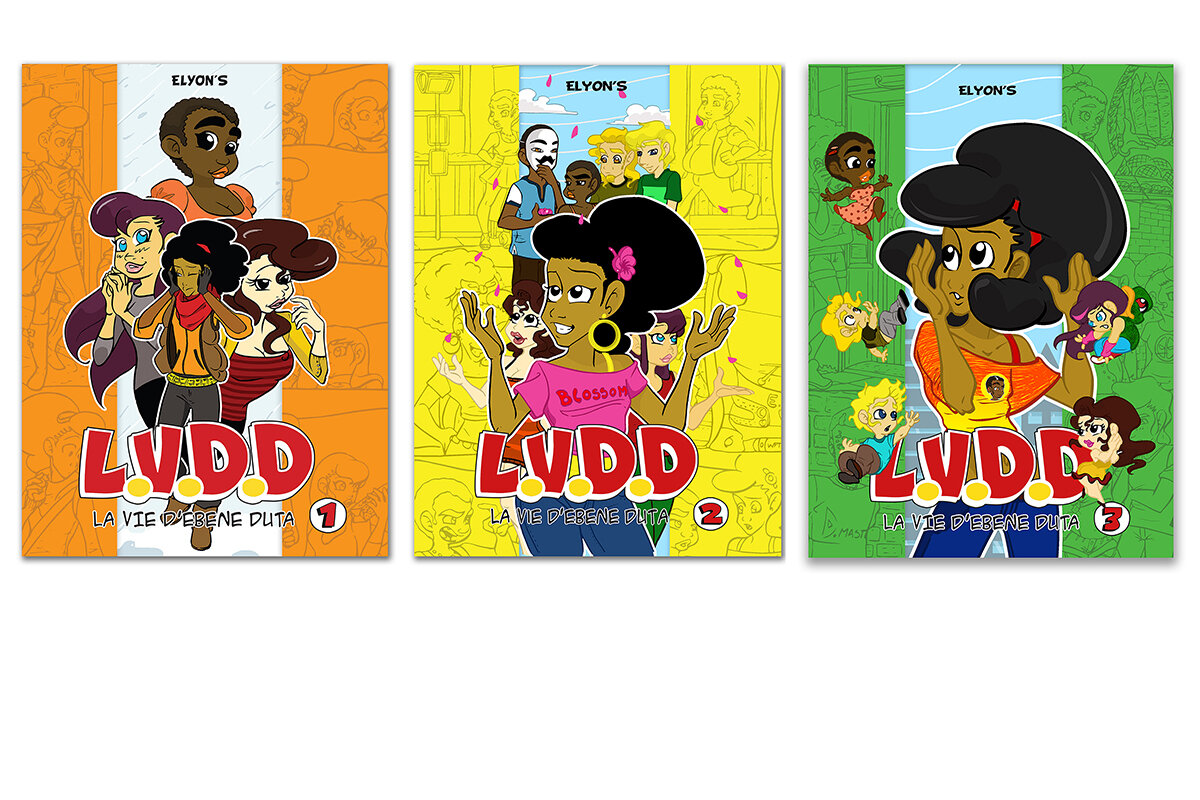

Two decades and a successful comic book series later, however, Ms. Épée Mandengue, who writes under the name Elyon’s, has engineered her own happy ending. And not only for herself. This year, she co-curated a virtual exhibition of African cartoons called “Afropolitan Comics,” which showcases work by artists from across the continent.

“When you say Marvel, or manga, or Asterix, people from all over can immediately imagine the world you’re talking about,” she says. “We wanted the same to be true for comic artists working in Africa.”

Year of the comic

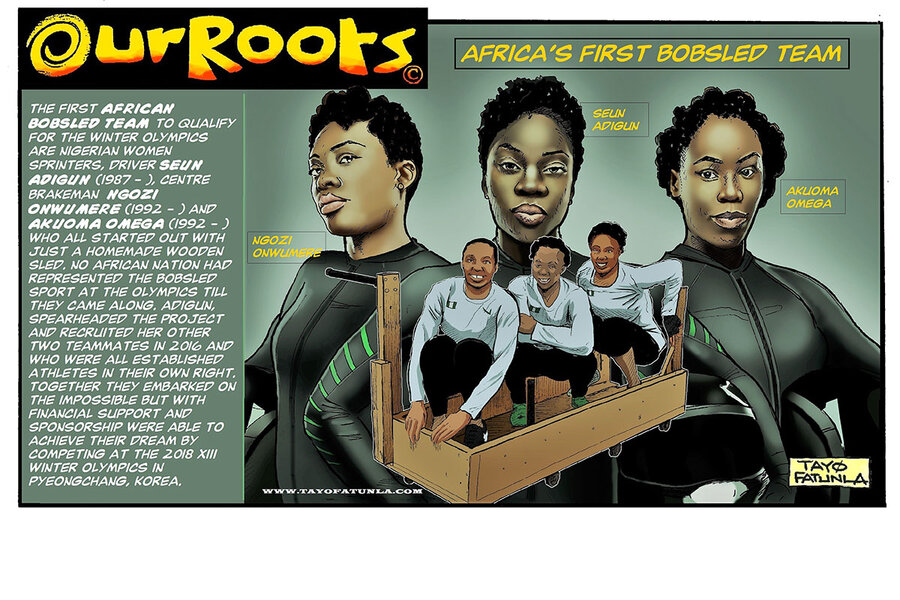

The exhibition website features samples of comic strips from across the continent: from a sci-fi thriller whose heroine is a teenage Mami Wati – a West African water spirit – who keeps flunking water spirit school; to “Our Roots,” a visual encyclopedia of Black historical figures from Barack Obama to Seun Adigun, captain of the first Nigerian Olympic bobsledding team.

“This is a quick engaging way for people to start learning histories maybe they were never taught in school,” says Tayo Fatunla, the Nigerian comic book artist behind “Our Roots.” After all, he reasoned, what better way to get people to love their history than to make it beautiful?

The Afropolitan Comics exhibit also had the backing of one of the world’s most comic-obsessed societies, France. It was sponsored by the French Institute of South Africa and la Cité internationale de la bande dessinée et de l’image, a massive French comic book museum and library, as part of a global, French-led celebration of the “Year of the Comic” in 2020.

“In France, comics are acknowledged as a serious form of art, and seen as an important artistic tradition,” says Selen Daver, the cultural attaché for the French Institute. In 2019, indeed, the French bought 48 million comic books, accounting for 16% of all book sales. “So within that tradition it was really important for us to also give space to African comic artists telling their own stories.”

Many of the artists whose work is showcased on Afropolitan Comics grew up steeped in the world of classic French bandes dessinées. But even as they devoured them, their relationship to the comics they loved was often an ambivalent one. Why were the only Black characters they saw the Africans who hovered around Tintin during his adventures in the Congo, “look[ing] like monkeys and talk[ing] like imbeciles” as the British Commission for Racial Equality described the book in 2007.

“At some point I realized, most of the comics I love are made by white men, and I’m a Black woman,” says Ms. Épée Mandengue. If she wanted to see herself on those pages, she realized, she’d have to be the one to draw it. And she did. Her signature comic, “The Diary of Ebène Duta,” follows the adventures of a Black teenager in Belgium, where Ms. Épée Mandengue herself attended university.

“You speak really good French,” a classmate of Ebène Duta’s tells her in one early scene. “For an African, that’s really rare.”

Unexpected upside

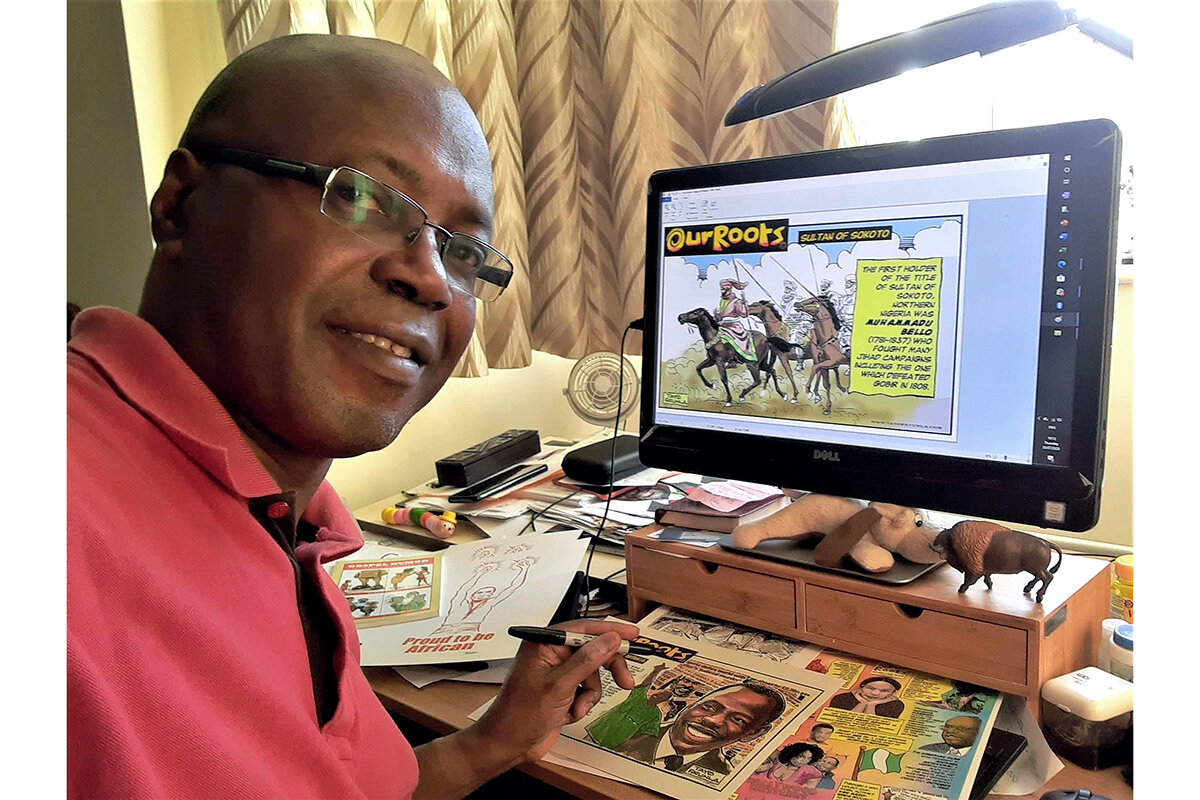

For Mr. Fatunla, the Nigerian artist, comics have always been a medium for talking about heavy subjects in a way that is accessible and engaging. He cut his teeth drawing political cartoons for Nigerian newspapers, and has spent much of his career making art based on his original “Our Roots” series, exploring the legacies of the African diaspora around the world.

“I want to show people that Black excellence exists everywhere,” he says, whether it be in the form of Yaa Asantewaa, a 19th-century queen in present-day Ghana who led a revolt against British colonialism; or Wizkid, a 21st-century Nigerian pop star.

The creators of Afropolitan Comics hope that the works featured will eventually form part of an in-person exhibition in France. But there has been an unexpected upside to making an art exhibition during a pandemic too. Because it is virtual, its reach is global.

“I would like this to reach new audiences and people who have no idea that this rich tradition of comics is happening on the continent already,” says Ms. Daver of the French Institute. “I hope it will attract people who hadn’t thought to look to Africa for comics before.”

And for young artists in Africa, the message of Afropolitan Comics is even simpler. Your stories matter. You belong.