From South Sudan to Australia: One man’s quest to save stories

Loading...

Growing up, much of Peter Deng’s world revolved around stories. In the cattle camps where he was raised in southern Sudan, “we passed down our history through songs,” he says.

When the country’s brutal civil war forced him to flee his home at the age of 18, he took those stories with him. And when, a decade later, he received the news that he was being resettled from the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya to Australia, the stories he’d memorized all those years before traveled there, too.

But as he made his life as a refugee in Australia, Mr. Deng began to worry. Many of the southern Sudanese he met in Australia had either been born abroad or were too young when they left to remember life there. They knew little of their community’s history. They tripped over the words when they tried to speak their mother tongues.

Why We Wrote This

Home isn’t just a place, but a set of stories. When South Sudanese refugee Peter Deng realized books about his country, language, and history were scarce, he decided to change that.

“I didn’t want people to forget where they came from,” he says. “I wanted them to know the history they were a part of.”

In 2009, Mr. Deng began scouring the internet for books on southern Sudanese history to share with other refugees in Australia, but quickly discovered that many were out of print or prohibitively expensive because they were so rare. He imported what he could from Kenya, the United States, and the United Kingdom, but realized that if he were to make his country’s literature and history more accessible, he needed to start printing it himself.

Mr. Deng had never worked in publishing. Since arriving in Australia he’d been an electrician, spray-painted the logo of a pet food company on buildings, made pastries, ran a day care, and started a butchery. But along the way, he’d earned a degree in international business at Victoria University in Melbourne, and so he figured, why not try book publishing next?

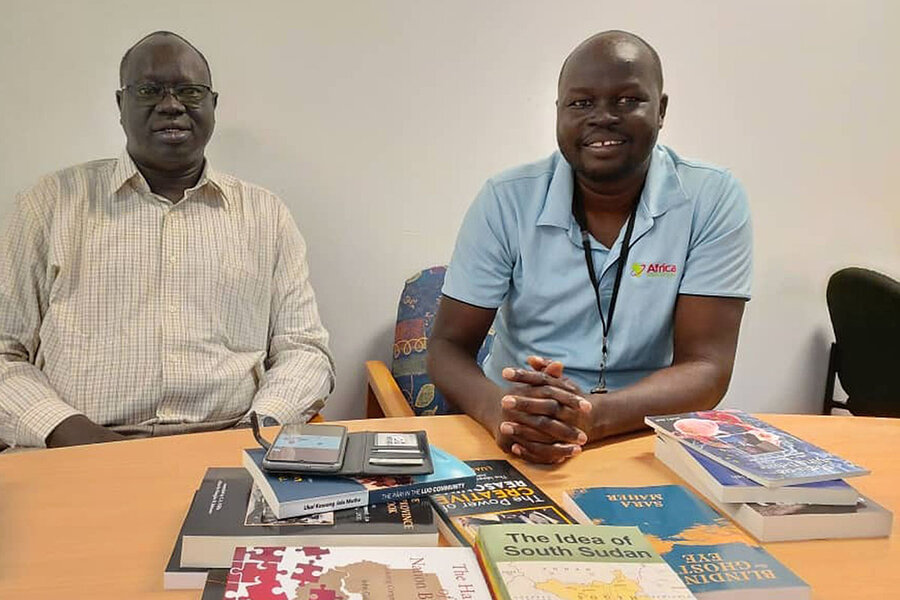

In 2012, he founded Africa World Books. Today, the company prints its titles largely on demand, which Mr. Deng says has allowed him to sidestep the traditional financial barriers to publishing and distribute a much wider range of texts. He sells not just the old-school histories of southern Sudan written by missionaries and Western academics, but also more contemporary history books, memoirs, and language textbooks written by South Sudanese themselves.

The books, he says, are meant to be a resource for both the South Sudanese diaspora and Australians curious about their new neighbors. “Australians are a kind people, but they don’t always know who we are,” he says.

Currently, Africa World Books stocks about four dozen titles, and Mr. Deng says its most popular are grammar manuals for languages commonly spoken in South Sudan – which became independent from Sudan in 2011 – like Dinka and Acholi.

Ajak Duany Ajak, a South Sudanese mining consultant who lives in Perth, like Mr. Deng, recently bought a book called “The Dinka’s Grammar” to learn more about the structure of a language he has spoken from birth. He says he hopes to eventually start teaching Dinka to younger South Sudanese in Australia.

“If you lose your language, then you lose your culture as a South Sudanese. It’s as simple as that,” he says. “And if we cannot read and write Dinka, there will come a time with all of us spread around the world that our stories written in Dinka will disappear.”

Like Mr. Deng, Mr. Ajak worries about what it means that so many South Sudanese don’t know their own homeland because of the wars that have convulsed it for decades. Hundreds of thousands live outside the country, and some 25,000 people born in either Sudan or South Sudan live in Australia.

“Reading our history can be part of our healing,” Mr. Deng says. “Because we come from an oral culture, this is a job none of my ancestors had, but I think it’s one they would respect.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of Victoria University, and incorrectly identified the town where Africa World Books was first founded.