Five years ago, the world shut down. COVID’s imprint lingers from politics to schools.

Loading...

Five years ago, the World Health Organization declared that the outbreak of a novel coronavirus, COVID-19, was a pandemic – a designation that in many ways marked the beginning of a new era in politics, public health, media, and our everyday lives.

The Monitor’s correspondents have covered all aspects of this transformation, from the pain of families separated, to divisive school board protests, to the discovery of quirky joy in new pastimes as an outlet. On this anniversary, they share some of the shifts they’ve noticed and how the pandemic continues to influence global societies today.

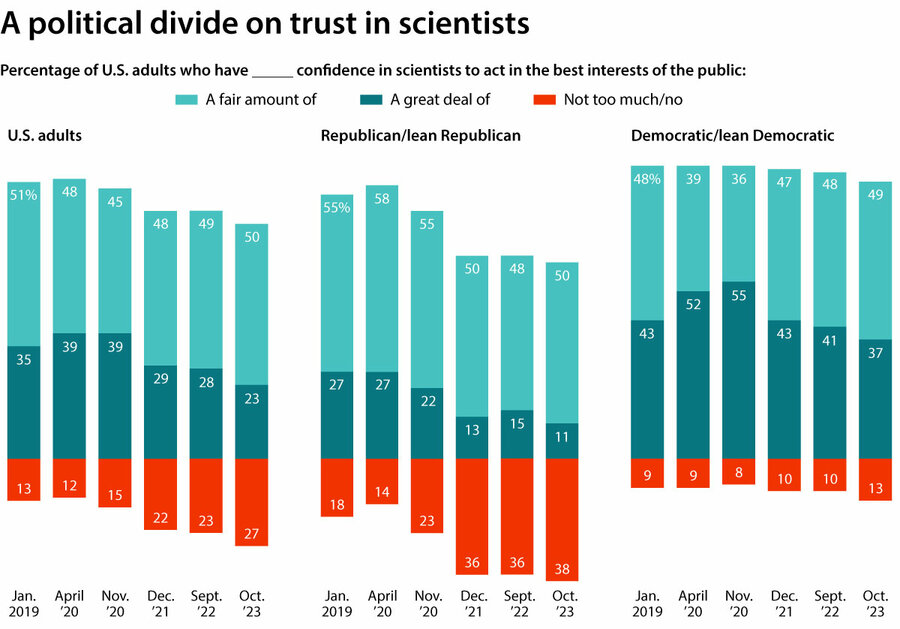

The pandemic took an immense human toll over the past half-decade. According to the WHO, more than 7 million people died because of the virus between 2020 and 2024, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention still attributes thousands of deaths every month to COVID-19. The economic toll of the pandemic and the regulations around it continue to fuel a mistrust not just of the government, but also of those with different perspectives about the virus, medicine, and health policy.

Why We Wrote This

It was foremost a public health crisis. But 10 of our reporters observe wider lasting effects – from the workplace and politics to religious life and trust in elites.

Not everything was negative. Pivots prompted by social distancing requirements ushered in new opportunities and cultural phenomena. Six years ago, “Zoom” was not another word for meetings or a way to see family online.

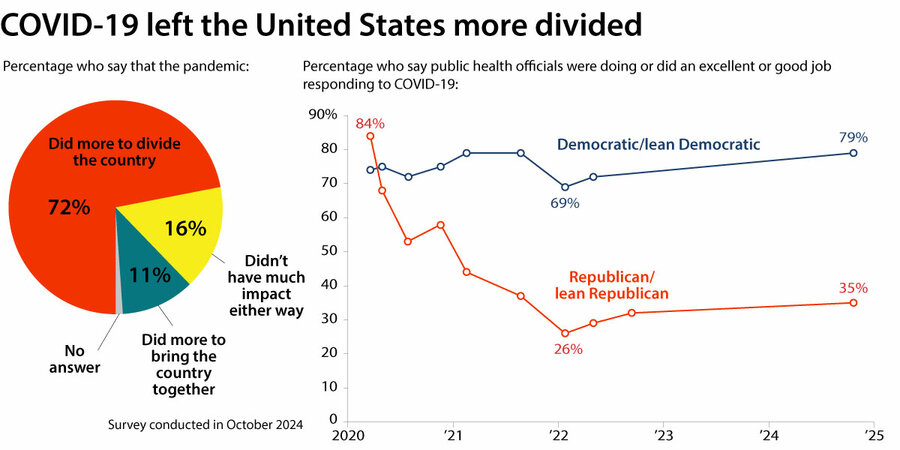

Still, according to a recent survey from the Pew Research Center, nearly three-quarters of adults in the United States say the pandemic did more to drive the country apart than to bring it together. It highlighted, and exacerbated, differences in values around the rights of the individual versus the rights of the community. Globally, polling as of 2022 showed a similar trend of nations feeling more sundered than united.

Many experts point out that the pandemic did not cause this fraying. COVID-19 arrived at a moment when distrust and division were already increasing, and as a new media environment was exacerbating those divides.

“When you put a pandemic into a highly volatile and divisive political context, we know it’s going to be incredibly difficult,” says Allan Brandt, a historian of medicine and professor of the history of science at Harvard University. “Repairing and understanding what just happened to the world over the past five years is going to be an important part of our future.”

We have dispatches from 10 Monitor writers from around the world to share with you.

“Science is real.” It’s also complicated, and so is our relation to it.

Some months into the COVID-19 pandemic, I moved to a progressive town in western Massachusetts where people liked to declare that they “believed in science.” They had the rainbow “Science is real” lawn signs to prove it.

My out-of-school children would ask me why so many science-lovers were giving us dirty looks from their cars as we went for maskless runs on empty streets. I’d just shrug.

Science is complicated, I’d tell them. That’s what makes it amazing.

But I knew something profound was happening – as did many of the scientists and public health thinkers I’ve interviewed over the past several years.

As the U.S. swirled into competing narratives of what, exactly, COVID-19 was, and how to respond to it, “science” regularly became a cudgel. Only people who didn’t believe in science itself, the rhetoric on one side went, would doubt the recent guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the official explanation for COVID-19’s origins, the need to enforce curfews. (All of those “facts,” of course, shifted during the pandemic.)

Meanwhile, a new media landscape fueled an outrage that turned scientists and public health officials into villains. This is part of what Syracuse University Professor Amy Fairchild describes as a “backlash movement” that has fundamentally reshaped our political and cultural landscape.

Missing from both stances was the acknowledgment that science is not itself a thing or a truth, but a beautiful, curiosity-driven process in which imperfect human knowledge is always changing.

“Science is always evolving. It’s always contested. There are always gaps. There have been terrific scientific debates around, I don’t know, salt,” says Dr. Fairchild. “Science is always working in a context where social values and priorities are at play.”

But the media and political forces underlying this pandemic made it particularly difficult for those working in science to live in that nuance – and it pushed many to declare certainties that ultimately undermined trust, experts say.

– Stephanie Hanes, environment and climate writer

In Michigan and beyond, an altered politics

For many Michigan voters, the garden centers were the final straw.

When states first began issuing stay-at-home orders five years ago in March 2020, as they grappled with the threat of a brand-new virus, Americans were largely supportive. In Michigan, Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s initial orders to close schools and businesses had widespread approval – even among Republicans.

But as shutdowns were extended and expanded, voters’ patience and confidence in their political and public health leaders began to waver. When Ms. Whitmer issued an executive order that April closing garden centers and plant nurseries, the pushback was so strong she was soon forced to rescind it.

A year and a half later, when I was on a reporting trip in Michigan, voters from both parties still brought up the closed garden centers. And while the anger from Republicans was more visceral, many Democrats also told me, in lower voices, that they believed that particular order had gone too far. Ms. Whitmer handily won reelection in 2022, thanks in part to the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade that same year, which helped boost Democratic turnout for several contested governorships.

Politically, the most lasting legacy of the pandemic may be the way it decimated trust in government. To be sure, the level of trust was already low – after hitting a brief high point following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, trust in government has stayed below 30% ever since late 2006, according to the Pew Research Center. But after the pandemic, officeholders from the state to federal level saw their approval ratings collapse, while anti-government sentiment rose overall, particularly among Republicans.

The garden centers in Michigan were a window into why. Many voters said Governor Whitmer’s order, which restricted an outdoor activity – gardening – seemed irrational and excessive, even at the time. It made them question the decisions of those in power and the evidence supporting other restrictions.

In hindsight, of course, it became clear that a number of measures, like school closures, likely did more harm than good. Even among those who still believe officials did the best they could with limited information, the impact on trust in government seems likely to linger for some time.

– Story Hinckley, national political writer

Sweden shows an alternative response

While much of the world was learning to grapple with a new and scary challenge, Sweden watched the pandemic unfold as if it were a movie. Eerie streets in New York and overwhelmed hospitals in Milan came as heart-wrenching scenes. But that was happening out there. In Sweden, cafés remained crowded. Children went to school. Many people did not wear masks.

There were some guidelines for distancing in public, and we were advised to stay home when sick and to limit gatherings. But it was largely left to the individual to decide what that meant.

At the time it was seen as an irresponsible gamble. Later it was called a success story. There were not more deaths in Sweden than in neighboring countries, despite a spike at the start. Students did not lose years of learning.

Some say Sweden lived through the pandemic in denial. That may be, while those in nursing homes faced the brunt of pandemic-attributed deaths. But the experiment may also have shown what Sweden intuited from the start. People like to be trusted as individuals. If that freedom is used responsibly, it builds more trust. Contrary to what happened in most places, Swedes reported feeling more united than they did before the pandemic.

Yes, Sweden continues to feel stiff and uninviting to those not already in the fold. But somewhere within its staunch individualism, Sweden managed to find an unusual togetherness that weathered a pandemic.

– Erika Page, global economy writer

A tough hit to education – and glimpsing paths to recovery

Early in 2022, groups of young students gathered in the school cafeteria in Elizabethton, Tennessee, to sound out words like “ball.” Tutors patiently helped each child blend the letter sounds together.

At the time, I was at this elementary school in the Appalachian Mountains covering Tennessee’s new tutoring corps. The state was using pandemic relief funding to invest in “high-dosage, low-ratio” tutoring. It’s one of the approaches that researchers say can best help students who are behind, as many still are, long after the pandemic’s disruptions.

The school’s principal offered a prescient warning. He worried the state wouldn’t extend the corps once federal funding ran out. That happened last summer.

“Things that we know work, like tutoring, using proven curriculum and instructional strategies, especially for literacy and math, those really still are lagging,” says Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

The learning loss kids experienced, and how it hit students in lower-income schools hardest, is one of the thorniest legacies of the pandemic. Education reformers are calling for more innovation, like bringing in-school tutoring back. Families are looking to alternative models: Homeschooling, while past its pandemic peak, accounts for 4% of the school-age population, up a percentage point since 2016. Charter school enrollment is up nearly 12%.

As the long-term recovery continues, the school in the Tennessee mountains offers a lesson. Students and teachers find joy in mastering the ABCs, but it takes persistence.

– Chelsea Sheasley, national news staff editor and former education writer

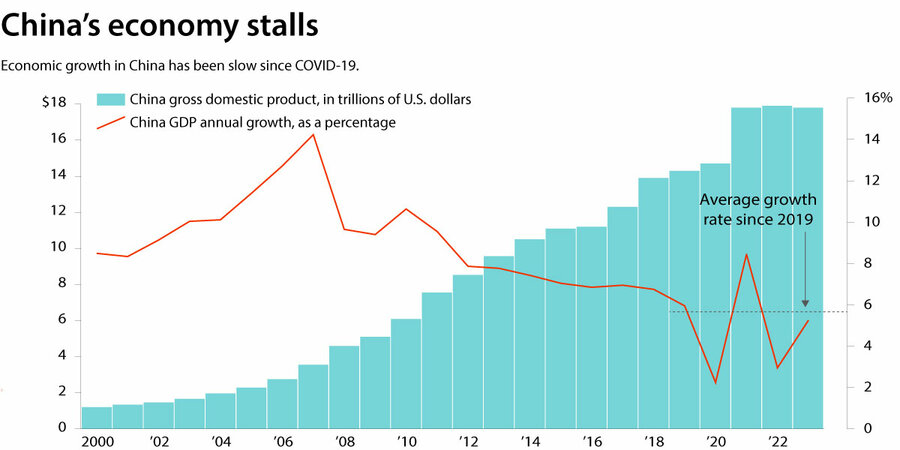

In China, an economic hit from striving for “zero-COVID”

Each time I bicycled to the tiny tea shop off a residential alley in Beijing, the talkative owner told me a little more of her story.

Hailing from the tea-rich Fujian province in southeastern China, she’d moved to Beijing with her husband and young son several years earlier to launch her shop. Business was brisk, she said, until some of the strictest pandemic lockdowns struck Beijing hard in early 2022. “Now, it’s horrible,” she complained in her rapid-fire Fujianese accent, surrounded by shelves full of tea but no buyers.

Traveling around China, I’ve asked scores of small entrepreneurs how their businesses are faring. Most of the time, they say, “It’s no good.” Months of mandatory closures ate away their savings – and too few customers have so far returned.

I often thought about the costs of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s insistence that authorities strive for zero COVID-19 cases. This top-down policy required massive testing and quarantining of the population, coupled with sealing off vast cities and shuttering most businesses whenever tiny outbreaks occurred. The policy proved untenable and was lifted in December 2022, but China’s economy is still struggling to recover.

The Chinese are adjusting to this new normal. A young graduate student in central China, hard put to find a job, said she’s pursuing a more laid-back lifestyle.

In Beijing, I pedaled to the tea shop to find that the hard-working owner had taken on a new gig to try to make ends meet. She’d turned her shop into a distribution point to help neighbors save on delivery charges – capturing a small return for herself.

“Sorry, I’ll be with you in just a minute!” she told me, as she sorted a grocery order. “No problem!” I said, smiling. My tea could wait.

– Ann Scott Tyson, Beijing bureau chief

Pandemic response spurs youth activism in Africa

When I moved to South Africa from the U.S. a decade ago, at the age of 25, many people in my life wondered why. By then, the country’s glittering moment as Nelson Mandela’s rainbow nation seemed firmly in the past. Instead, it was in the uncertain throes of adolescence, beset by corruption scandals and political infighting.

But I was struck how impermanent these troubles felt to many South Africans my age. In the U.S., I had been raised to believe that ideas and institutions changed slowly. Young South Africans, on the other hand, lived in a society that had transformed radically less than a generation before. For them, the country’s future was wet clay, nearly totally malleable, and they were eager to get their hands dirty. As I traveled Africa, the world’s youngest continent, I saw this kind of hope and determination everywhere.

Over the last few years, I have watched as the pandemic and its aftermath cranked up the volume on the ambition of young Africans to build societies more just and democratic than those of their parents and grandparents. From Nigeria to Senegal to Kenya, young people have poured into the streets. They were protesting leaders they say failed them during the pandemic, whether in the form of restricting personal and political freedoms in the name of disease control, or failing to shield their populations from a tanking global economy.

Even when those protests have been brutally suppressed, as in Mozambique, where hundreds of young people died protesting a highly disputed election last year, their demands remain urgent. One young woman there, Estância Nhaca, told my colleague Samuel Comé something that echoes across the continent.

“It’s not over yet.”

– Ryan Lenora Brown, Africa editor

Returning to places of worship

The pandemic’s effect on faith services was drastic. Houses of faith stopped holding in-person services overnight. Congregants found themselves worshipping alone at home over Zoom, rather than sitting shoulder to shoulder with their community. Some houses of worship sued states, arguing that closure orders aimed at public health were harming religious freedom. Faith leaders worried congregations wouldn’t return, that the pandemic might spell a precipitous drop in an American religious life that was already becoming more secular.

Their worries were not unfounded. Over the past several decades, researchers had tracked a steady pattern of religious decline. But a surprise emerged from the pandemic: Over the past five years, the number of religious Americans has stabilized.

About 24% of U.S. adults said their faith grew stronger as a result of the pandemic, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center in 2020. Only about 2% said their faith became weaker. In Pew’s newest survey on religion, concluded last year, some 83% said they believe in God or a universal spirit.

“Cognitively, this sense of faith getting stronger or deeper or more mature from the pandemic may have contributed to the stability we’ve seen in the past few years, maybe not causing religious growth overall, but at least halting the pattern of decline,” says Chip Rotolo, a religion and public life research associate at Pew.

Communities typically pull together in the face of disaster – though a global pandemic is many degrees larger than other examples, says Dr. Rotolo. After the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001, Pew data showed unity among religious communities across the U.S.

Today, most people who would normally attend faith services in person are back to doing so. “There can be a sense, when events like this happen, that people want to seek meaningful community like they might find in their religious communities, or start being more engaged,” he says.

– Sophie Hills, religion writer

On campus and beyond, a harsher edge to politics

The pandemic acted as a catalyst for political radicalization. Social isolation and rampant online misinformation combined to push many people into more extreme political positions – and in some cases, actions.

On my college campus, I saw students suddenly itching to have an outlet for their frustrations. After the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, Black Lives Matter protests erupted across the U.S. While the majority were peaceful, some resulted in looting and arson as protesters descended on deserted downtowns. The Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol was a shocking outburst of political violence, as Trump supporters attempted to disrupt the peaceful transition of power.

A March 2021 survey found 15% of Americans agreed that “Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.” That number rose to 23% in September 2023, but dipped back down to 18% this past fall.

More recently, we’ve seen the once-unthinkable glorification on social media of Luigi Mangione, the man accused of murdering UnitedHealthCare CEO Brian Thompson. And there’s been an increase in threats against politicians. In 2018, the Capitol Police investigated 5,206 threats against members of Congress; in 2021, it investigated 9,625. The number has been above 8,000 ever since.

– Nate Iglehart, staff writer

Mexico’s informal workers persist – without security nets

For many informal workers, like Obdulia Montealegre Guzmán, who sells corn-based treats like huaraches at outdoor markets in Mexico City, making it through the pandemic with her business and family intact came down to ingenuity.

“We stayed home for a month, but never really stopped working,” says Ms. Montealegre. Her daughter helped create a marketing plan for her parents on social media. They now accept to-go orders via WhatsApp, greatly upping daily sales.

I have been in touch with Ms. Montealegre several times over the past five years. She has always had an optimistic outlook, even when she was wrapping her business in industrial-size plastic wrap as an early-days health measure against the spread of COVID-19. But I was surprised to hear that today, she sees the pandemic squarely in the rearview mirror.

Challenges facing her and her neighbors – from growing inflation to a weakening peso – have no through lines to the pandemic, she says. It’s more a reflection of governments that for decades haven’t managed the economy well. Almost 60% of Mexican laborers are considered informal wage-earners who don’t have access to social security or employment benefits like paid leave.

There was no notable drop in trust in public officials in Mexico following the pandemic, in part because that trust has historically been low in Mexico and in the region. Data from Latinobarómetro, a regional polling firm, found that only 1 in 5 people in Latin America expressed trust in their governments between 2009 and 2018, for example.

“This kind of work is really exhausting and means just hustling all the time,” says Ms. Montealegre. “But our challenges long predated COVID.”

– Whitney Eulich, Latin America editor

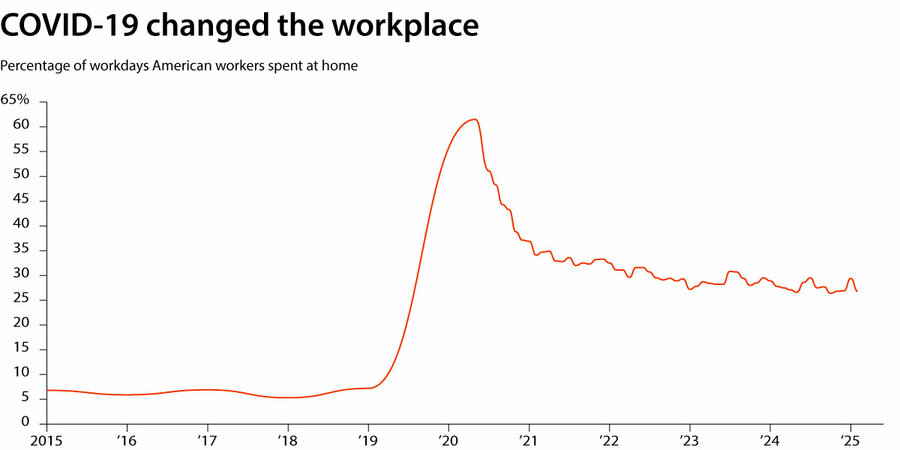

In a changed workplace, will in-person work make a comeback?

My first newsroom, which housed the student newspaper I worked for in college, was dynamic. It was filled with activity as we whipped stories into shape, argued over grammar, and gently coaxed the best out of each other. I assumed that professional newsrooms would also be hotbeds of activity where you could learn through osmosis.

But the reality was less romantic. When I started at the Monitor in 2023, the pandemic had emptied out offices, newsrooms included. The spirited discussions that for me defined journalism mostly happened on Zoom or Slack.

As the youngest person on staff, I wondered how this would affect my career. Some researchers say that when you’re just starting out, working in person is essential for learning. One friend, a software engineer, once texted me that he “can actively feel [his] career growing faster” when he works face-to-face.

Now, even as many employers aim for a greater return to offices, this challenge is affecting not just the news media but a host of industries.

It’s not that newsroom camaraderie is gone. I still feel connected to my colleagues, even if edits happen over Zoom. Yet it’s hard to imagine that workplaces will ever be quite the same.

Today, as people trickle back to the office, we’re getting some of that old newsroom energy back. And though how we come together has changed, one thing hasn’t: Journalism – or, really, any work – can only happen through collaboration.

– Cameron Pugh, staff writer and editor

This article was reported by Stephanie Hanes in Northampton, Massachusetts; Story Hinckley in Richmond, Virginia, Erika Page in Madrid (with pandemic visits to Sweden); Chelsea Sheasley in Boston; Ann Scott Tyson in Seattle and Beijing; Ryan Lenora Brown in Johannesburg; Sophie Hills in Washington; Nate Iglehart in Boston; Whitney Eulich in Mexico City; and Cameron Pugh in Boston.