From Sterling to Bundy, how to respond when speech offends?

Loading...

Donald Sterling. Paula Deen. Juan Williams. Cliven Bundy. Phil Robertson.

Each of these individuals has landed in hot water thanks to controversial comments that unleashed similar responses – public outrage, a media blitz, and professional sacking or suspension. Along with scores of others, they represent a treadmill of inflammatory speech scandals that have tripped up America for decades.

Yet for all the attention devoted to the off-color comments – even President Obama weighed in on the Sterling scandal – Americans’ collective reaction to controversial speech may be far more revealing than the headline-making remarks themselves. Society’s reaction is more about style than substance, commentators say, suggesting Americans haven’t made as much progress as they think they have on issues of race, religion, gender, and sexuality.

Furthermore, incidents of inflammatory speech force Americans to confront the fine line between protecting free speech and fostering a tolerant, pluralistic society.

Society’s response to offensive speech “seems to me a very ritualized performance of outrage that doesn’t get anywhere in the end,” says Orin Starn, a cultural anthropologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

The scandals themselves, Professor Starn adds, are “a peephole into the dark racial id of an America that’s still very much caught up in the ugliness and drama of race.”

While remarks like those made by Mr. Sterling and Mr. Bundy are nothing new, it’s worth noting how the US public’s reaction to such comments has changed. In fact, “politically incorrect” statements on race, gender, and homosexuality were so commonplace in the first half of the 20th century that the concept of inflammatory speech practically didn’t exist.

“This country, for nearly all of its history, has been a place where someone could say racist or homophobic or sexist things and not be challenged, because the thoughts that supported them were part of the fabric of this society,” says Hub Brown, a professor of broadcast journalism at Syracuse University in Syracuse, N.Y.

That started changing in the 1960s, says Kate Ratcliff, professor of American studies at Marlboro College in Marlboro, Vt.

“The political mobilizations of the 1960s and ’70s changed the culture in important ways,” she writes in an e-mail. “People of color, women, gays and lesbians made inequalities visible. They also became more visible themselves, occupying new positions in society. Our heightened sensitivity to expressions of racism, sexism and homophobia reflect these transformative changes.”

In the ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s, the ubiquity of news only served to amplify controversial comments and extinguish any concept of privacy.

In fact, the 21st-century response is not unlike the scapegoating ritual of ancient societies, says Steven Benko, professor of religious and ethical studies at Meredith College in Raleigh, N.C. “When these scenarios flare up, [the offenders] become scapegoats,” he explains. “They stand in and represent an attitude or a worldview. All sins are heaped upon the scapegoat, who, for purification, is driven out of town. It’s like saying goodbye to that worldview.”

Of course, we’re only fooling ourselves, Professor Benko says: “Ultimately what we’re playing is whack-a-mole. By not having a larger, longer, sustained conversation about race in this country,” we’re not making progress, “we’re just playing whack-a-mole.”

And there’s the rub. In all the hullabaloo raised over a controversial comment, the public often misses the larger point.

“The focus on racist language and speech potentially obscures the deeper and more underlying dimensions of racism,” Professor Ratcliff says.

For example, Sterling is alleged to have engaged in multiple incidents of housing discrimination against black and Latino tenants in Los Angeles, and the US Department of Justice sued him in 2006. While his recent comments to his female companion about blacks made headlines, the alleged housing discrimination – which was settled for almost $3 million, with Sterling denying the accusations – did not.

As Starn told Newsday in an April article about the Sterling scandal, “The actual task of fixing inequality in America is a gigantically complicated one. And it’s not a problem that will be fixed with a few sound bites and declarations of good intentions.”

Yet not all is gloom and doom. If history is any indication, Americans are now far less tolerant of intolerance, says Robert Thompson, professor of TV, radio, and film at Syracuse University.

“The fact that this kind of speech is considered scandalous is progress,” says the pop-culture expert and cultural historian. “We as a society ... are more sensitive to these things. That’s brought us out of the ‘Mad Men’ era.”

Of course, America even elected a black president. So things are good, right?

Not really.

“As a country, we thought we had made a lot more progress with race than maybe we have,” Benko says. “We think we’re in a postracial society. Uh-uh.”

Beyond these issues of race, incidents of inflammatory speech get into another area filled with debate: free speech rights. In essence, which do Americans value more: individual freedom or a tolerant, pluralistic society?

There’s no easy answer, says Dennis Parker, director of the Racial Justice Program at the American Civil Liberties Union in New York, acknowledging that the juncture of these interests is a constant source of conflict in the ACLU offices.

“How exactly do you draw the line ... between a spirited debate and racial or sexual harassment?” he asks. “It’s not always clear.”

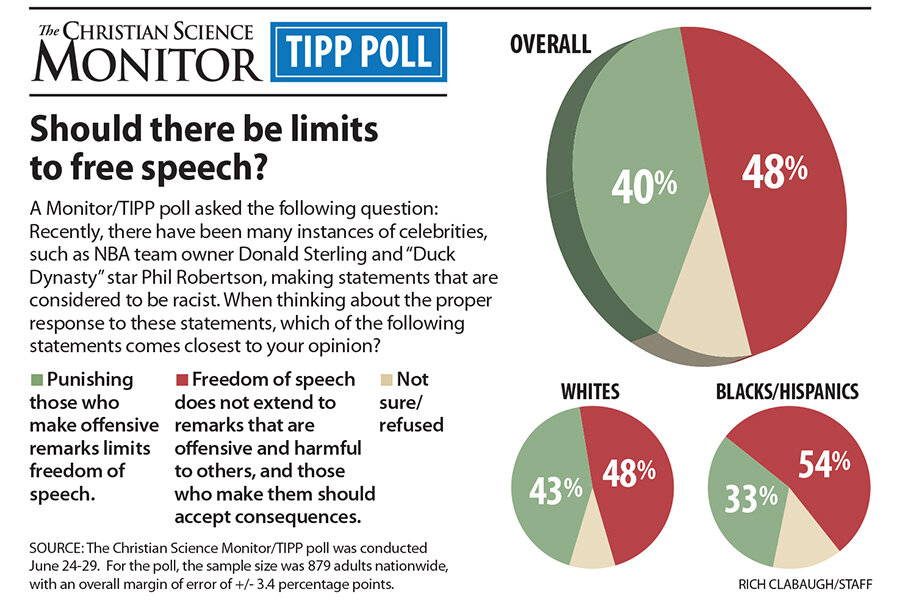

The US public is similarly split on the issue. When asked to consider the appropriate response to statements like those made by Sterling and Mr. Robertson, Americans were divided, according to a recent Christian Science Monitor/TIPP poll. Some 40 percent said punishing those who make offensive remarks limits freedom of speech, while 48 percent said that freedom of speech does not extend to such remarks and that those who make them should accept the consequences.

Nonetheless, defending free speech is often thought of as intrinsically patriotic. Consider the US Supreme Court decision from June 26 in which the justices ruled unanimously that Massachusetts went too far when it created 35-foot buffer zones around abortion clinics to keep demonstrators away from patients. While the court is famously divided on abortion, it appeared united in defending the free speech rights of abortion opponents.

As Lewis Maltby wrote in an op-ed in the Chicago Tribune, “Defending our constitutional rights does not come with an a la carte option. That’s why the American Civil Liberties Union defended the right of Nazis to march in Skokie [Ill.] in 1978.” Mr. Maltby, president of the National Workrights Institute in Princeton, N.J., and former director of the ACLU National Task Force on Civil Liberties in the Workplace, continued, “As President Barack Obama remarked, ‘When ignorant folks want to advertise their ignorance, you don’t really have to do anything. You just let them talk.’ ”

In fact, the key to addressing America’s prejudices is free speech, says Harvey Silverglate, an attorney and civil liberties advocate in Cambridge, Mass.

“The only way we will, as a nation, solve problems of race, religion, homosexuality ... is to avoid turning ... these issues into a ‘third rail’ such that expression of a prohibited view ... kills a career or endangers one’s position,” he writes in an e-mail. “Race problems require truly free speech and free thought to solve them, not the hypocrisy of political correctness.”

But Ratcliff sees problems with such free speech arguments. “They don’t wrestle enough with the competing needs of society to both protect the rights of individuals and to safeguard the human dignity of all its members,” she says.

Countering speech with more speech is not always that simple, says Ratcliff, citing instances in which offensive comments come from an employer or someone physically threatening.

“[S]peech carries with it cultural and historical baggage and speech acts do not always occur between people who can be considered equals,” she says.

Imposing consequences, she argues, is beneficial to society: “We register and solidify our values through the imposition of consequences.”

So what’s the appropriate reaction in the case of, say, Ms. Deen? According to many free speech advocates, the answer is to let the marketplace decide. Fans may refuse to watch her shows and buy her cookbooks, thereby forcing her off the Food Network and out of her Random House publishing deal.

As such, her words have consequences, even if her speech is protected.

“Most people seem to want to rewrite the First Amendment thusly: ‘I get to say whatever I want, no matter whether it offends or intimidates you, and you are prohibited from doing anything about it,’ ” writes Professor Brown in an e-mail. “[T]hat’s not the First Amendment. The First Amendment guarantee of free speech is a protection against government, not the consequences of one’s verbal ignorance.”

Mr. Silverglate sees it differently.

“[J]ust because an employer might have the legal authority to fire someone for expressing unpopular views, this does not mean that it is wise ... to be so ready to fire someone for the mere expression of unpopular views,” he says. “We have become ... a society in which people are too readily penalized for expressing ostensibly unpopular opinions.”

And unpopular opinions aren’t going away. As the saying goes, “prices will rise, politicians will philander” – and public figures will continue to make imprudent, career-ending comments.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing, Professor Thompson says.

“Celebrities are the Trojan horse by which we get these debates into mass public conversation,” he says.

In other words, it’s a teachable moment, adds Starn.

“When somebody says ‘fag’ or something derogatory about African-Americans, that’s kind of a teaching moment when we as a country are able to think about race and to reaffirm the fact that we’re committed as a country not to use nasty words,” he says. “At least, that’s an optimistic view of what these social dramas are about.”