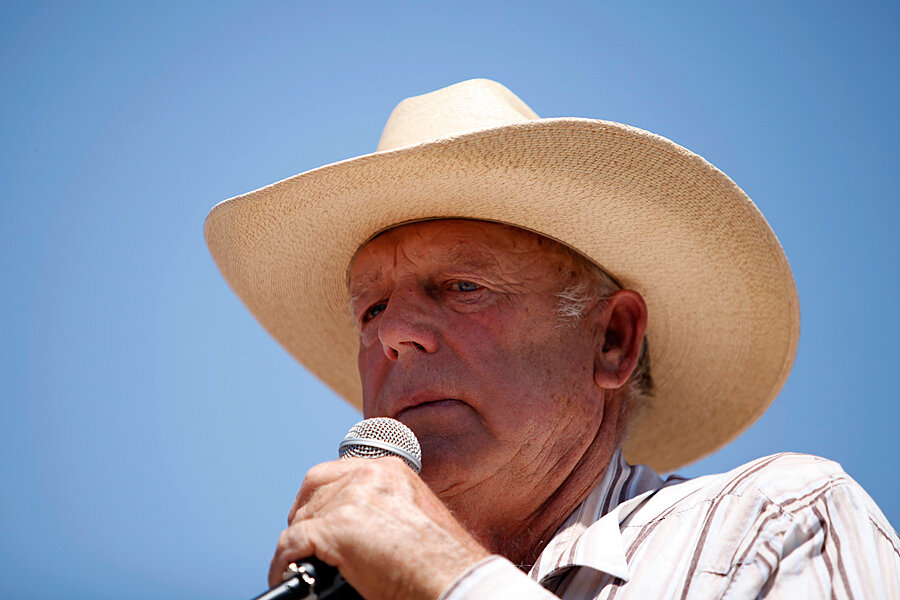

In Cliven Bundy beef about 'the Negro,' shades of white privilege

Loading...

Cliven Bundy, the Nevada rancher and federal antagonist, is defending his remarks that “the Negro” may have been better off in slavery than in the modern welfare system, in the process drawing an unusual series of dots between ranching, race, and the meaning of white privilege in post-civil rights America.

After being condemned for his off-the-cuff observations about poor blacks he has seen “doing nothing” in North Las Vegas, Nev., Mr. Bundy, who became a political star on the right after standing on 10th Amendment grounds against the US Bureau of Land Management over federal grazing fees, insisted that, “I’m right.”

His “Negro” comments became, some political analysts say, a prism reflecting the views of a certain subset of very conservative Americans, primarily older and white, who have struggled to come to terms with the expansion of federal largess under America’s first black president.

To be sure, even Bundy’s hardiest supporters called the comments “blatantly racist,” in that he seemed to suggest that America should again enslave black people. In explaining his point in subsequent interviews, Bundy insisted he had the best interest of black people at heart – that the current system enslaves blacks in a different way. “I am not a racist,” he insisted.

But his views also point to another basic tension in the fight over who should control the massive tracts of high desert and grazing grounds on the Western plateaus: the specter of white privilege in politics.

After all, if Bundy believes blacks are worse off with government subsidies, that leaves his own situation up for scrutiny: He owes $1 million in grazing fees to American taxpayers for using federal land, but is using a states’ rights argument to get out from under the overdue bill.

“He has been quoted as saying, ‘I don’t recognize the United States government as even existing,’ ” writes Olivia Nuzzi, on the Daily Beast website. “Remarks such as that, unsurprisingly, endeared him to the far-right.”

(When the BLM seized some of his cattle earlier this month, a posse of armed Bundy supporters challenged the action and forced the BLM to relent, release the cattle, and go home.)

That “welfare for me but not for thee” paradox is what troubles many critics of tea party-tinged groups and personalities. Even as some tea partyers bemoan benefits to minority groups, they take full advantage of subsidies afforded to them, whether in the form of corporate tax breaks or Medicare.

In an interview with CNN on Thursday night, Bundy, not one to mince words, acknowledged that paradox. When asked whether he was a welfare queen for squatting his herd on federal land, Bundy replied, “I might be a welfare queen,” but “at least I put red meat on the table.”

Researchers who study the beliefs of conservative Americans said Bundy’s phrasing isn’t that unusual. “It’s coming out of religious white supremacy, which is that slavery wasn’t so bad, because slaves were well treated, and the Civil War was unfortunate because the federal government acted lawlessly and overwhelmed the states,” says Garrett Epps, a University of Baltimore law professor and author of “Wrong and Dangerous: Ten Right-Wing Myths About Our Constitution.”

“A guy like Bundy, he’s discussing having driven through a neighborhood that has African-Americans in it – that’s the extent of his contact [with black people] in Nevada,” adds Mr. Epps.

But at Community Digital News, Jennifer Oliver O’Connell, who is black, suggests that the Bundy soundbites as circulated by the media don’t accurately reflect Bundy’s logic.

“What Bundy is trying, and sadly failing, to do is make the connection between government control and the fomenting of grievance and unrest among minorities,” she writes. The question is whether “dependency on government handouts – whether in subsidized housing, food, or land – [is] a new form of slavery that kills purpose, motivation and independence?”

Then she laments: “While despising the messenger and the way the message is being delivered, we fixate on all the wrong things.”