Trump vs. Harris? In Florida, abortion is the biggest question on the ballot.

Loading...

| Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

Melissa Shiff, clipboard and campaign literature in hand, strides up to a home on her list and knocks on the front door. An older man appears, sees Ms. Shiff’s “Harris Walz” T-shirt, and bristles.

“We’re Trumpers! We’re pro-life!” he declares, and then shuts the door.

Ms. Shiff, the leader of Florida Women for Harris – out canvassing in suburban Fort Lauderdale on a recent Saturday – steps back onto the driveway and pauses.

Why We Wrote This

After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, ballot measures supporting abortion rights helped drive turnout for Democrats in 2022. Now, a vote in Florida will test the long-term strength of that political backlash.

“I just wish people would be kind,” she says, shaking her head.

In these final weeks of the 2024 campaign, the marquee national contest is the presidential race between Democrat Kamala Harris and Republican Donald Trump. But here in Florida, a onetime electoral battleground that now tilts Republican, the biggest unknown heading into November isn’t about the candidates on the ballot.

It’s about abortion.

Floridians are facing a referendum that would guarantee abortion access up to fetal viability, about 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation. That’s far beyond the six-week window (before many women even know they’re pregnant) that became state law in May. To pass, the proposed state constitutional amendment needs 60% of the vote. Public polls show supporters within striking distance.

When the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the nationwide right to abortion in June 2022, the political backlash was immediate and intense. Abortion-rights advocates quickly began mobilizing around state ballot measures to ensure abortion access – and repeatedly won. Since the overturning of Roe v. Wade, every state ballot measure aimed at supporting abortion rights has passed, including in conservative states like Kansas, Kentucky, and Ohio.

Lately, however, abortion foes seem to be finding their footing in fighting back. And as shock over the Supreme Court’s ruling fades and the patchwork of state abortion laws becomes the “new normal,” it may become harder for abortion-rights activists to challenge it.

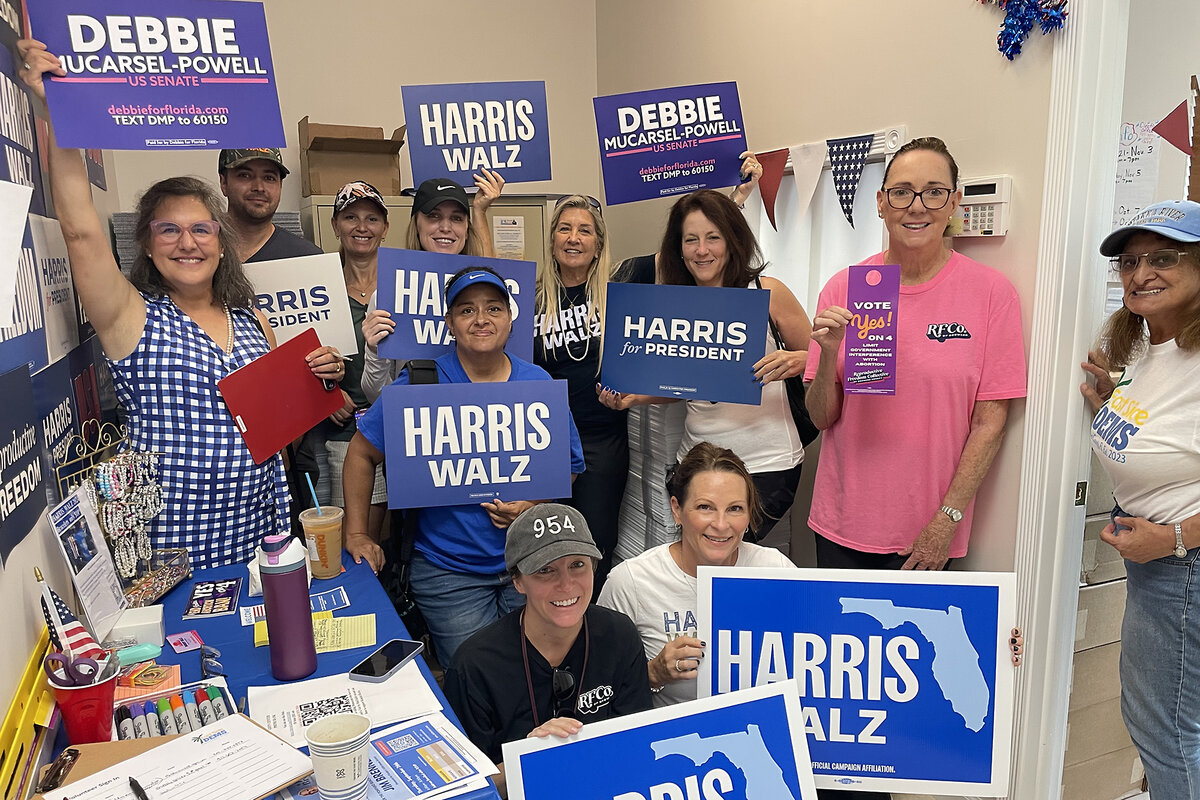

As such, Florida’s vote next month presents a key test of whether abortion-rights measures can still draw floods of voters to the polls, even in red states – or if the energy around that issue is waning. Recent polls have shown the Senate race here tightening, with national Democrats infusing cash into their effort to defeat GOP Sen. Rick Scott. Democratic nominee Debbie Mucarsel-Powell, who’s still an underdog, has made protecting abortion rights a centerpiece of her campaign. Some Floridians may choose to split their votes, backing Republicans for president and senator but voting yes on the measure known as Amendment 4.

“I can see a sizable portion of Republican women voting yes,” says Susan MacManus, a veteran Florida political analyst.

But, she adds, the opposition TV ads are “quite good,” and growing activism from Catholic and other religious organizations is bolstering that side. “Church people are high turnout voters,” Ms. MacManus says. The Latino vote is another key battleground, with both faith-based and secular activists doing outreach for and against the measure.

The impact of Hurricane Helene – and the looming threat of another hurricane – has added even more uncertainty, as large swaths of the state are focused on cleanup and the restoration of basic services. Some polling places have been damaged, and voters in affected areas may not receive mail-in ballots.

Ten abortion measures on state ballots this fall

Florida is far from alone with Amendment 4. Nine other states have constitutional amendments on the ballot this November that would ensure varying degrees of abortion access.

In key ways, however, Florida’s measure stands apart. The 60% threshold for passage is a high bar. At the same time, the nation’s third-most-populous state is a giant peninsula that can make traveling out of state for an abortion difficult – especially for women of modest means. Before the six-week ban kicked in, Florida was where women from neighboring Alabama (which has a total ban) and Georgia (whose six-week ban has been restored by the state Supreme Court while a legal challenge continues) could travel for abortions.

Millions of dollars have poured in from around the country to fund outreach by both sides in a state where campaigning is notoriously expensive – especially on TV, with 10 major media markets. Nationally, abortion-rights groups have been outraising opponents 8 to 1, according to an analysis by the watchdog group Open Secrets and The Associated Press.

Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, a strong abortion opponent, has sparked controversy by using the tools of government in his effort to defeat the measure. In early September, at a state party dinner, he called out fellow Republicans by name who had yet to donate to the anti-Amendment 4 effort. And his secretary of state launched an investigation into signatures used to get the measure on the ballot, including signatures that had already been validated.

Most recently, the DeSantis administration successfully defended in court a website created by the state health agency claiming the amendment “threatens women’s safety.” The plaintiff, the Floridians Protecting Freedom political committee, had argued that the state “unconstitutionally entered the debate.” On Sept. 30, a Florida judge ruled the site could stay up.

Then there’s Florida’s most famous resident – former President Trump, who repeatedly skirted questions about how he would vote on Amendment 4 before finally, under pressure from anti-abortion activists, landing on his final answer: no on the amendment.

But Mr. Trump’s past comments indicated he felt otherwise. Last year, after Governor DeSantis signed the six-week ban passed by the state Legislature, Mr. Trump called it “a terrible mistake.” In late August, the former president said that a ban after six weeks was “too short” and, “I’m going to be voting that we need more than six weeks.” A day later, he reversed himself.

Mr. Trump has also said he would veto any federal abortion ban – despite the fact that he nominated the conservative justices who overturned the nationwide right to abortion. If such a ban were to pass, it would effectively override state measures like Amendment 4.

Add to the mix newly publicized comments by Melania Trump, who joins a long line of Republican former first ladies in voicing support for abortion rights. In her forthcoming memoir, obtained by The Guardian, she frames the issue as “a fundamental right of individual liberty.” A promotional video, released Oct. 3, elaborates on her views.

Might all these mixed messages from the Trump family hurt the effort to defeat Amendment 4? Aaron DiPietro, legislative affairs director for the conservative group Florida Family Voice, says no.

He suggests that Mr. Trump’s own journey on Amendment 4 reflects where a lot of centrist Florida voters will land as they work through the issues. “Many will say, ‘Hey, I might not agree with current Florida law, but Amendment 4 is too extreme,’” he says.

Dubious claims by both sides

Proponents of Amendment 4 hope the measure will drive turnout for Democrats, as the issue did in the 2022 midterms when an expected “red wave” did not materialize for Republicans. But a big difference now is that Mr. Trump is on the ballot, perhaps the biggest turnout driver for both sides.

Voters have faced a barrage of mailers and TV ads that may leave some confused. The most prominent opposition ad, sponsored by the Republican Party of Florida, attacks the amendment as vague and claims it would allow “abortion at any time.”

Experts note that the language of the amendment was approved for inclusion on the Florida ballot by the state’s highest court on the basis of its clarity, and that existing definitions in Florida law, such as the meaning of “viability,” must be followed if the amendment passes.

A TV ad by supporters of Amendment 4 – claiming the Florida abortion law has no “real” rape or health exceptions – was rated “mostly false” by PolitiFact. The current Florida law does contain a health exception, and other Florida law requires exceptions for cases of rape and incest for up to 15 weeks of pregnancy.

Anna Hochkammer, executive director of the Florida Women’s Freedom Coalition and a leader on Amendment 4, agrees with Mr. DiPietro that the battle will be fought in the middle.

“The math is pretty straightforward in Florida to get to 60%,” Ms. Hochkammer says.

Her approach: Win about 85% of registered Democrats, two-thirds of independents, and 2 out of 5 Republicans. She knows it won’t be easy, especially as Florida has grown increasingly red. Registered Republicans (now 39%) surpassed Democrats (32%) as the state’s largest voting bloc in 2021.

“My working hypothesis is that Floridians, even Florida Republicans, tend to tack libertarian, and so they perceive referenda as a brake on their elected officials,” Ms. Hochkammer says. “You have to go out of your way to talk to the Republican voters who have every intention of splitting their ticket on this issue.”

Some Florida Republicans planning to vote for Mr. Trump and yes on Amendment 4 see no contradiction in their views.

“I don’t love all of Trump’s policies, but on foreign policy, I believe he projects a little more strength” than Ms. Harris, says Jared, a lawyer in Tampa who asked to withhold his last name. But on the abortion measure, he says, “I have little sisters, and I don’t want the government to police what women can do.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated Oct. 7, the date of its initial publication, with the latest status on judicial review of Georgia’s six-week abortion ban.