In Arizona and beyond, an abortion uproar has Republicans scrambling

Loading...

| Washington

When Donald Trump stated early this week that abortion policy should be left to the states – addressing a long-standing question about his stance – the once and possibly future president may have thought the issue was behind him.

But it wasn’t to be.

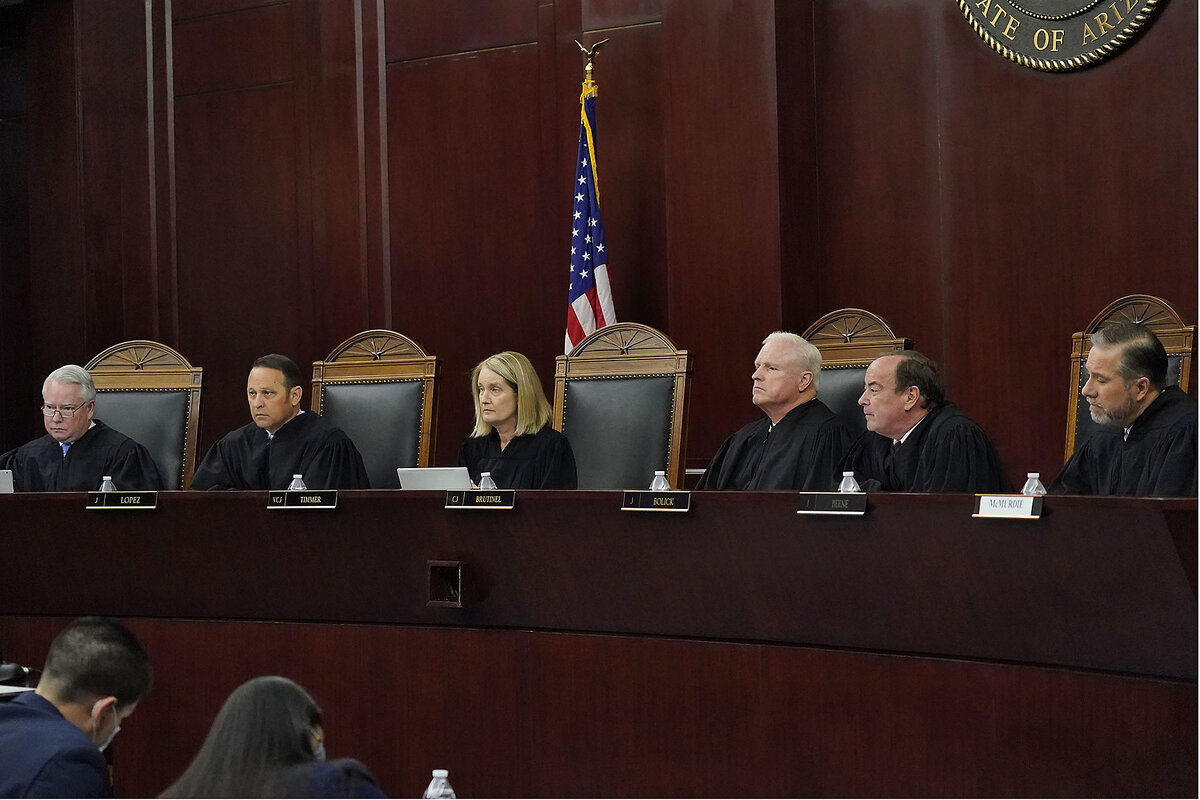

The very next day, the Arizona Supreme Court dropped a bombshell, reviving an 1864 state law banning all abortions, except to save the life of the mother. On Wednesday, the closely divided Arizona House erupted in cries of “Shame! Shame!” when Republicans defeated an effort to overturn the ban.

Why We Wrote This

Leaving abortion access to states means stakes are growing for the 2024 election – and roiling Republicans over how to respond.

Now, the issue is poised to go before Arizona voters in a referendum on the November ballot – likely driving up turnout in a key battleground state. Florida voters, too, will have a say on abortion, after the state’s highest court ruled last week that a constitutional amendment guaranteeing abortion rights until fetal viability can appear on the ballot. Activists in other states have also put abortion on the ballot or are working on it.

Since June 2022, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade – the landmark ruling that guaranteed a nationwide right to abortion – the issue has galvanized women and driven up election turnout.

Now, in a presidential election year, the stakes are higher. And abortion has become a defining issue.

“Democratic women, independent women, and pro-choice voters have been mobilized by the decision to overturn Roe,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia. “So every time there’s an additional ingredient that gets thrown into that bowl – whether it’s IVF or, now, a law from 1864 – it’s just more ammunition for the Democrats.”

States in flux

In vitro fertilization, or IVF, made headlines in February, when the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that embryos created via this technique should be considered children. The state Legislature quickly passed a law protecting IVF providers from liability regarding the embryos they store, but the case still attracted national attention. One IVF provider, in Mobile, Alabama, announced last week it was shutting down over “litigation concerns.”

Another case, this one out of Texas and recently argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, is challenging the legality of a widely used abortion drug called mifepristone. Part of the argument leans on an 1873 law known as the Comstock Act to support a ban on mailing abortion pills. Many women living in states banning surgical abortion rely on medication to end an unwanted pregnancy.

When Roe was overturned almost two years ago, then-President Trump earned high praise from abortion opponents. By appointing three anti-abortion justices to the Supreme Court, teeing up a majority to overturn Roe, he helped fulfill abortion foes’ long-held dream.

A reversal by Trump

Now that Roe is gone, religious conservatives and other abortion foes who are a crucial part of Mr. Trump’s base want more: nationwide limits on abortion access. In a videotaped statement Monday, the former president and presumptive 2024 GOP nominee declined to go there, to the dismay of anti-abortion activists.

“We are deeply disappointed in President Trump’s position,” said Marjorie Danenfelser, president of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, in a press release.

On Wednesday, Mr. Trump doubled down, telling reporters in Atlanta he would not sign a national abortion ban, a reversal of both a 2016 campaign promise and statements from his time as president. He also said the new Arizona abortion ban went too far, adding “that will be straightened out.” Mr. Trump, who used to identify as “very pro-choice,” is seen by many as having adopted an anti-abortion posture for political reasons.

Today, despite the criticism from his base, Mr. Trump may be smart to punt the issue to the states and avoid further alienating moderate voters who might be gettable.

“Purely politically, I think Trump made exactly the right move,” says historian David Garrow, author of the book “Liberty and Sexuality.” “It takes him out of the conversation.”

But the reality is that, in fulfilling his core promise to overturn Roe, Mr. Trump unleashed forces that likely boomeranged against the GOP in the 2022 midterm elections – and could come back to bite Mr. Trump and the party this November.

In 2022, a predicted “red wave” failed to materialize, leaving a slim Democratic Senate majority in place and only a narrow GOP takeover of the House. In Michigan, a key presidential battleground state, Democrats won the governor’s mansion and both houses of the Legislature for the first time since 1983. A successful ballot measure enshrining abortion rights in the state constitution likely helped push up turnout.

Other states – including solid Republican Kansas and Ohio – have passed referendums supporting abortion rights since the fall of Roe.

This November, with two unpopular candidates expected to top the major-party tickets, the dynamic is different. But early signs are that Democrats will benefit more than Republicans from Roe’s demise.

According to a KFF Health Tracking Poll released in March, 1 in 8 voters say abortion is their top voting issue, and among those voters, a majority are Democrats. Among Black women voters, 28% cited abortion as their top issue, as did 22% of Democratic women.

Abortion isn’t the only big issue

But it’s likely a stretch to say that this week’s uproar in Arizona over abortion has already delivered the state to President Joe Biden. With almost seven months until the Nov. 5 election, the economy and immigration are still the most important issues overall, polls show.

Unforeseen events could also sway votes. “If the [abortion] law remains on the books and the ballot proposal makes the ballot, it will help Biden,” says Kim Fridkin, a political scientist at Arizona State University. “But to what extent? Not everyone’s a single-issue voter. It will be a very close race no matter what.”

Mike Noble, a nonpartisan pollster based in Phoenix, also urges caution when looking at the Arizona electorate. Though the state has shifted toward the center in recent years, he says, the state still leans right – but with an independent streak.

“Abortion will be a key wedge issue for Democrats here, but it won’t be the No. 1 issue,” Mr. Noble says. “Inflation and immigration are definitely the top two pain points, not only for Republicans but also independents.”

In Florida, abortion-rights activists are bracing for May 1, when a ban on abortion after six weeks’ gestation goes into effect. A state constitutional amendment on the ballot in November would enshrine abortion protections. But the bar for passage is high: 60% of the vote.

A concerted get-out-the-vote effort on the abortion measure could bring coattails for President Biden in a state that used to be the biggest battleground in the country, but has shifted rightward in recent cycles – though not as much as 2022 suggested.

Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis’ 19-point reelection victory two years ago was not the new normal for Florida, says Susan MacManus, professor emerita of political science at the University of South Florida, pointing to a weak Democratic turnout effort. “There’s no question – no question – that Florida’s elections will go back to the old pattern of being close,” she says.

But whether having abortion on the ballot can help Mr. Biden is another matter.

Some voters, for example, could choose to vote for protecting abortion rights while also voting for Mr. Trump as president.

“Some people’s vote for president is more dictated by how they feel about the pressing issues that affect them daily,” Dr. MacManus says. “I’m not saying [the abortion measure] won’t help Democrats. I think it will. But it’s a lifetime between now and when people start early voting.”