Even as Judiciary panel spars over Supreme Court vacancy, signs of civility

Loading...

| Washington

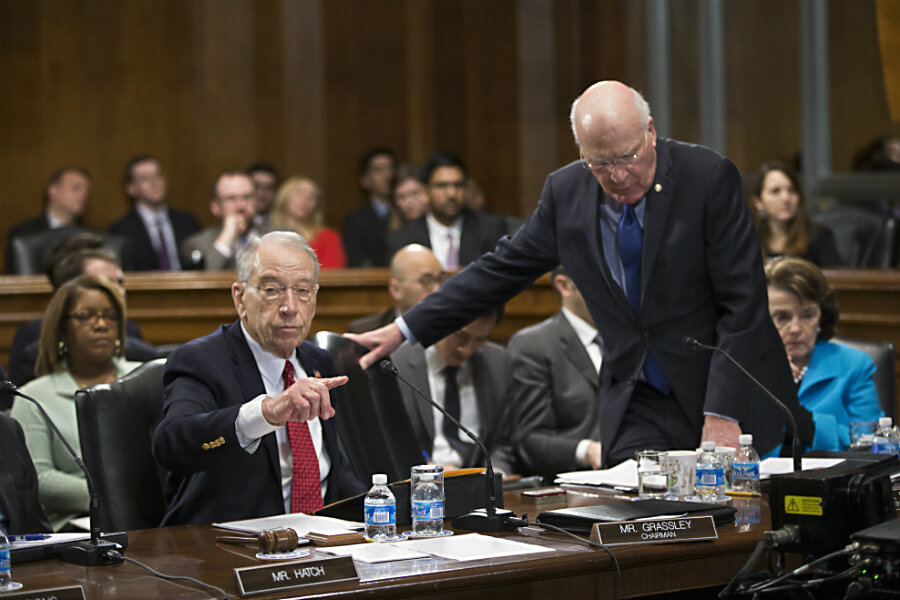

Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch looked away from his prepared remarks. “Mr. Chairman,” he said Thursday, addressing Sen. Charles Grassley, the GOP leader of the Senate Judiciary Committee. “I’m really concerned about this, because it seems to me, this is a presidential election mess.”

He was talking about the highly contentious issue of filling a US Supreme Court vacancy in a presidential election year. “I’ve never seen the country more at odds, more on edge about a presidential nomination process,” the senator from Utah went on. Given those circumstances, he concluded, Republicans have “every right” to wait on filling the vacancy left by the death of conservative Justice Antonin Scalia last month.

Then it was Democrat Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s turn. She pushed the button on her microphone. Somberly, the Californian turned to Chairman Grassley – who has been under scathing criticism from Democrats for refusing to even hold a hearing on a nominee. In a senatorial tone, she expressed her “great respect” for him “and for most of my colleagues on the other side.”

A bipartisan chuckle rippled among the senatorial aides, and turned into an outburst of laughter among the senators, including the Republican chairman from Iowa. Everyone had picked up on the “most” qualifier that signaled the partisan reality – but also civility – that characterizes one of the Senate’s most contentious committees.

Let it not be said that the Judiciary Committee’s senators can’t laugh or work together, even in the most difficult times. On the same day that they lined up their arguments for and against dealing with a Supreme Court nominee, they also joined their colleagues in a 94-to-1 vote to approve a bill to help states combat opioid and heroin abuse.

The bill had passed out of Judiciary unanimously on Feb. 11 – one of 21 that have cleared the committee with bipartisan support so far this session.

Indeed, despite the deep division over the nomination, Democrats and Republicans on the committee are still working to get a bipartisan criminal-justice reform bill to the floor for a vote.

“We get a lot of things done that people don’t know about,” said Senator Hatch in an interview after the committee’s meeting – its first full debate on the nomination issue since Justice Scalia’s death and the announcement that Senate Republicans would not take up a nominee until the next president is in power.

Given the intensity of the politics surrounding the debate, one might have expected some table pounding or at least very heated exchanges at Thursday’s meeting – which was packed to the point of overflow in anticipation of fireworks. It was, instead, a largely respectful, sometimes humorous, exchange. The senators voiced sharply different views, but they listened to one another and mostly stuck around for the debate.

“What we’re trying to do is hold out the hope that cooler heads will prevail on the Republican side,” said minority whip Sen. Richard Durbin (D) of Illinois, in an interview. “I believe that public sentiment favors a hearing and a vote. And I believe that Senator Grassley, for example, is going to hear it back home. There may come a moment when they decide to try a different approach, so we tried to set the stage for that to happen.”

Not a chance, Grassley said during the meeting.

The Senate Judiciary Committee is ground zero for many of America’s most controversial issues. Abortion, crime, pornography, school prayer, civil rights – all have crashed like “waves” upon its paneled walls, as one senator put it. As Hatch said, “the committee is built to argue.”

Which is exactly why respect is so important, say Hatch and others.

“There is a recognition on the part of all of the leaders of the committee that civility is especially critical when dealing with issues like this,” says Mark Gitenstein, an attorney in Washington who served as chief counsel to the Judiciary Committee for the Democratic majority under then-chairman Joe Biden.

Mr. Gitenstein had a front seat at President Reagan’s nomination of conservative Robert Bork for the Supreme Court – who crashed and burned under withering fire from Democrats. Yet Gitenstein calls Grassley a “statesman” who recognizes that an agreement to disagree is crucial to making the Senate function.

But that doesn’t take one jot away from the serious nature of the nomination clash itself, which Gitenstein calls “the continuation of a 30-year war over the Supreme Court.”

Beneath the senators’ mostly calm citations of the Constitution and history, of judicial precedent and public consequences of a long vacancy, rhetorical fingers are pointed like missiles at the other side, with Republicans blaming Democrats and vice versa.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R) of South Carolina said that they are setting a precedent for the last year of a president’s second term – and perhaps even the fourth year – to be off limits for future nominations to the highest court in the land.