Trump targets Big Law. Why that matters to the rest of us.

Loading...

As it began fighting for its life in federal court last week, the law firm WilmerHale turned to the story that most budding lawyers hear before anything else.

It’s 1770, and a group of British soldiers is on trial after killing five colonists in the Boston Massacre. John Adams, a prominent voice for independence, has chosen to defend them. Despite widespread criticism at the time, America’s second president later described it as “one of the best pieces of service I ever rendered my country.”

The British crown had a penchant for punishing lawyers who argued for causes it didn’t like. While it took place before the Revolutionary War, the Boston Massacre trial helped establish the bedrock principle that the U.S. government would have no such power. Every defendant has the right to a lawyer, and every lawyer has the freedom to represent whom they choose.

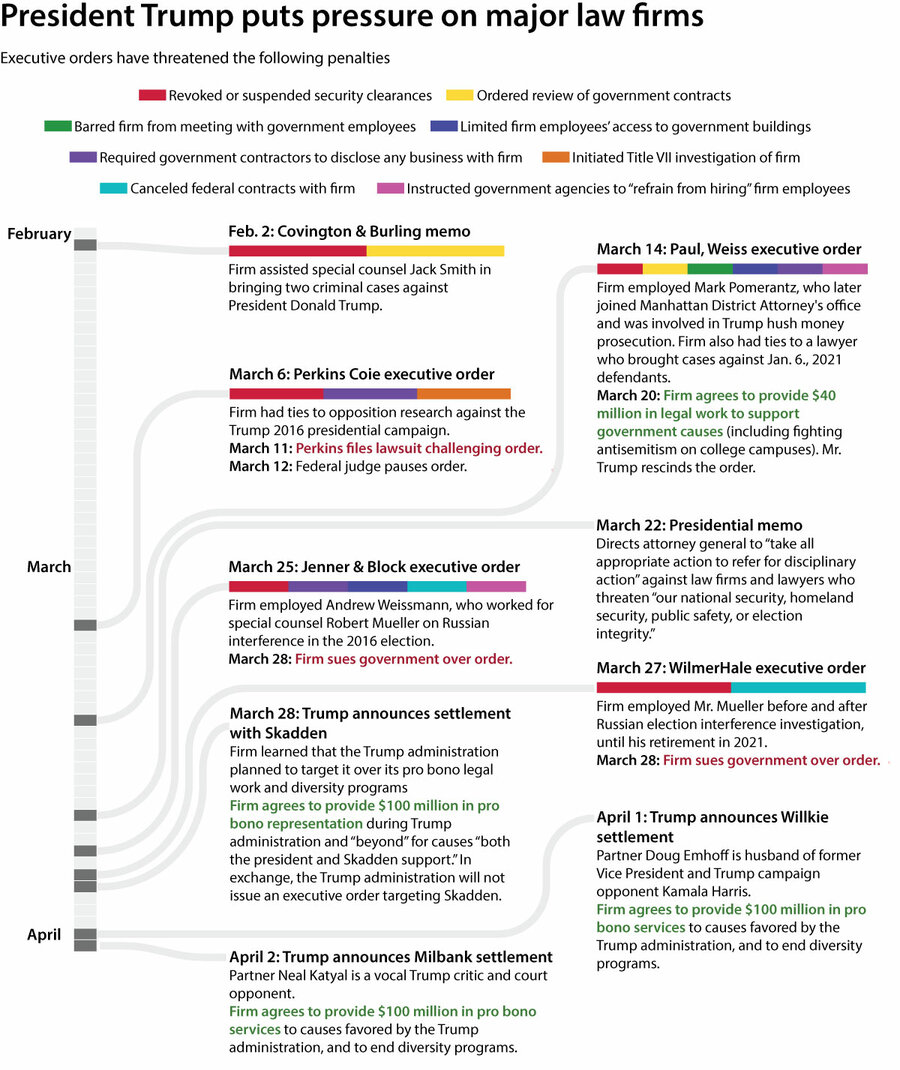

The Trump administration is now – according to the WilmerHale lawsuit and numerous legal observers – endangering that principle. In a series of executive orders and memos issued over the past month, President Donald Trump has ordered sanctions on major law firms. The firms, he says, have supported his legal and political enemies and, more broadly, undermined U.S. policy and security interests. The orders inflict penalties that could financially and reputationally hamper the firms. More orders could come, the White House has suggested.

Some firms are fighting back in court, while others have struck deals to avoid possible ruin. Overall, a climate of fear and confusion has settled over the cadre of elite law firms known familiarly as Big Law. Many lawyers interviewed would only speak to the Monitor anonymously out of concern they could attract unwanted attention to their firm.

These actions may be unprecedented in American history, but they echo actions taken in other countries where democracy has been declining. While Americans may have little sympathy for the soft hands and power suits of America’s corporate white-shoe law firms, legal experts warn that the stakes are that high. A fearful, compliant legal industry could open the door to more serious abuses of rights and freedoms.

“There has always been a tradition of lawyers challenging the government,” says Leslie Levin, a professor at the University of Connecticut School of Law. “This is attempting to make [them] reluctant to do that.”

Leveraging government access

In late February, Mr. Trump issued a memo targeting Covington & Burling LLP. Noting that the firm had helped former special counsel Jack Smith, who brought two criminal prosecutions against the president, he instructed senior federal officials to revoke security clearances for the firm and to evaluate government contracts with Covington.

The following weeks brought executive orders targeting Perkins Coie LLP and Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. Again, the firms have ties to Mr. Trump’s political opponents. Again, the orders revoked security clearances and ordered evaluations of their government work—even limiting access to federal buildings. Orders targeting two other firms have followed, along with a broader presidential memo calling for accountability for law firms and lawyers who threaten national security, public safety, or election integrity.

“Democrats and their law firms weaponized the legal process to try to punish and jail their political opponents,” said Harrison Fields, White House principal deputy press secretary, in a statement.

The executive orders, he added, “are lawful directives to ensure that the President’s agenda is implemented and that law firms comply with the law.”

The orders are also designed to hit Big Law firms where it hurts most: their wallets. Firms typically take on major constitutional cases pro bono, so while they may have a big impact on American democracy, they have next to no impact on the bottom line. Big corporations are their most lucrative clients, and government access is a key selling point to that clientele. Losing that access means losing revenue.

But while each firm in Mr. Trump’s crosshairs faces similar risks, their responses have differed.

Three firms have sued, arguing that the orders abridge constitutional rights to free speech, due process, and assistance of counsel. Four firms, meanwhile – including three that had not yet been targeted by Mr. Trump – have negotiated settlements with the White House. In exchange for tens of millions of dollars of pro bono work supporting the government’s causes, the firms will not be targeted by the president.

Exactly what is motivating firms to fight or bargain is unclear, but observers speculate that those with the most corporate revenue at stake are least likely to stand up to the government.

Meanwhile, sources and news reports say that major firms are refusing to take certain cases that they believe could anger the White House. In court last week, a U.S. Department of Justice attorney said, “There certainly may be more” executive actions coming, Reuters reported.

Big Law as big business

The extent to which some firms have folded at the first sign of danger is worrying to many lawyers and legal experts. But for others, firms are making understandable moves to avoid existential threats. Yet others say that they believe a political reckoning for the industry is overdue.

Attorneys in Washington have expressed that it’s a delicate balance for law firms.

“It’s easy to say in the abstract that you’d love them to fight back. But when your firm is targeted, it’s not abstract,” says one lawyer. “Employees’ jobs are on the line. The firm’s ability to advocate for clients is on the line. And we’re only two months into a four-year administration.”

Two companies that ranked among the 10 most profitable Big Law firms in recent years – Paul, Weiss and Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom – negotiated agreements. Earlier this week Mr. Trump also announced agreements with Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP, as well as Milbank LLP, which announced its deal Wednesday afternoon. Doug Emhoff, husband to Mr. Trump’s 2024 election opponent, Kamala Harris, is a partner at Willkie. Neal Katyal, a vocal Trump critic, is a partner at Milbank.

Paul, Weiss Chairman Brad Karp, in a firm-wide email sent after its agreement became public, described the situation as an “existential crisis” that “could easily have destroyed” the company. He also criticized other law firms, which, instead of supporting them, he said, “aggressively solicit[ed] our clients and recruit[ed] our attorneys.”

Mr. Karp added that the agreement “will have no effect on our work and our shared cultural values.” The Trump administration, he continued, “is not dictating what matters we take on, approving our matters, or anything like that.”

Thomas Cerabino, Willkie’s chairman, echoed this sentiment in the White House’s announcement released Tuesday. “The substance of that agreement is consistent with our Firm’s views on access to Legal representation by clients ... and our history of working with clients across a wide spectrum of political viewpoints,” he wrote.

According to a former partner at a major law firm who asked not to be named so he could speak candidly, negotiating agreements with the government is “an excellent business decision.”

“Some firms were exceptionally zealous and provided a lot of aid to people supporting causes the Trump administration opposed or causes that were personally damaging to Trump or his supporters,” he adds. “I don’t see any problem with the Trump administration saying you should provide pro bono services for causes you don’t necessarily agree with – that has always been an ideal of the profession.”

Other lawyers are worried about the precedent the agreements set, however, and the chilling effect it already appears to be having in the legal industry.

Profits over ethics?

Critics both inside and outside law firms say the firms are choosing money over morals and self-interest over the Constitution. For Rachel Cohen, who resigned from Skadden last week, this is an existential crisis – but it’s a crisis that requires a defense of the Constitution, not a negotiation.

“I have made plenty of moral compromises before. But this moment is existential,” she wrote in a LinkedIn post two weeks ago.

“If being on this career path demands I accept that my industry ... will allow an authoritarian government to ignore the courts,” she added, “I refuse to take it any further.”

Some Big Law firms share her view. WilmerHale and Jenner & Block sued the Trump administration last week. Perkins – which says the executive order against it could cost the firm one-quarter of its total revenue – had already challenged the government.

Federal judges have issued orders temporarily blocking parts of Mr. Trump’s orders against all three firms. The firms, judges said, face an immediate, concrete injury and are likely to succeed with their claims.

“There is no doubt this retaliatory action chills speech and legal advocacy, or that it qualifies as a constitutional harm,” said Judge Richard Leon, who is overseeing the WilmerHale case.

In the Perkins case, the executive order appears to violate the First Amendment and the law firm’s due process rights, said Judge Beryl Howell, according to The Washington Post. “It sends little chills down my spine,” she added.

In addition to the possible constitutional violations, judicial rules already exist to address concerns of the Trump administration. Rule 11 in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure holds that pleadings in court must be “nonfrivolous” and cannot be “presented for any improper purpose.” If a party believes a law firm is weaponizing the justice system for political ends, for example, it can ask the judge to sanction the opposing party.

In targeting specific firms with executive orders, the Trump administration no longer needs Rule 11.

“The whole point of these [orders] is they don’t have to ask the judge,” says Walter Olson, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute.

If the orders are upheld, he adds, “You have to worry, as a lawyer, that they’re going to come after you [just] because they don’t like the arguments you made.”

A tilted playing field?

That is not how the U.S. legal system is supposed to operate, experts say. In what’s known as an adversarial system, it’s presumed that parties arrive in court on relatively equal footing in terms of resources and lawyering skills. At that point, the best arguments win, and justice is served.

If independent law firms are afraid of advocating for causes the federal government dislikes, the playing field is tilted even more in the government's favor. The best arguments may not win. Justice may not be served.

“So many of the rights that we now take for granted were actually won by advocates in this system – going up against government lawyers often,” says Lindsay Langholz, senior director of policy and program at the American Constitution Society.

There is hope in how some firms are fighting back, legal experts say. But given the number of negotiated agreements, there is also skepticism. It appears that the industry best placed to fight for its rights against a grudge-fueled presidency with a maximalist view of its own power is doing so only cautiously.

“I’m shocked and dismayed by how brittle these institutions have turned out to be,” says one lawyer at a major firm who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

“This is about the fundamentals of who we are and the rule of law, and the fact people can’t see past their pockets for this. It’s a sad state of affairs,” the lawyer adds.

Looking at recent history, this response may be unsurprising. In Hungary and Turkey – to name two backsliding democracies – popularly elected leaders have weakened the judicial branch of government in part by empowering only lawyers willing to toe the party line.