This is how it looks when Congress gets along

Loading...

| Washington

Following last year’s passage of bipartisan highway and education bills, the United States Senate is taking up another broad piece of legislation – this time on energy – in a further sign that Republicans and Democrats can work together, even in an election year.

Congress hasn’t passed broad-based energy legislation since 2007. America’s energy situation has drastically changed since then, but partisan politics and election-year roadblocks have sidelined past attempts to adjust US energy policy to a more diverse and lower-cost power landscape.

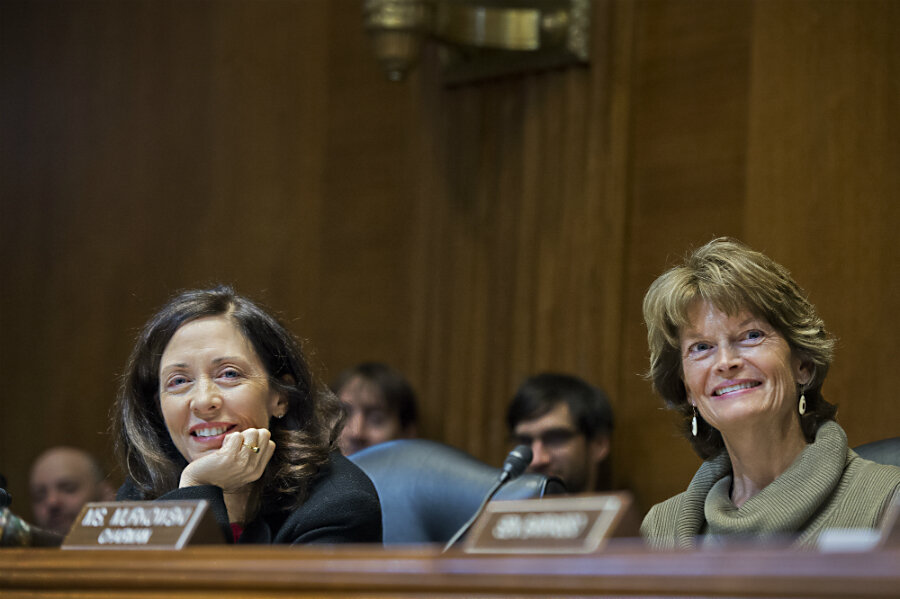

This year may well be different, in large part because of the efforts of the bipartisan bill’s managers, energy committee chairman Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R) of Alaska and the ranking Democrat on the committee, Sen. Maria Cantwell of Washington.

These are two women who, above all else, want to get things done, say those who know them. It’s a picture of how bipartisanship works – through their reliance on close communication, regular meetings, and a willingness to compromise.

When asked about the bipartisan nature of a bill on a subject that can be fraught with tension (think fossil fuels, climate change), committee member Sen. Joe Manchin (D) of West Virginia points to Senators Murkowski and Cantwell. “Look at the leaders of the bill. Very reasonable, very good people, practical people that aren’t playing hyper-politics.”

A Republican counterpart on the committee echoes his sentiments. “It was pretty clear in committee that Lisa and Maria wanted to get something bipartisan,” says Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, also of West Virginia. She says the bill’s broad support among committee members is due to the inclusiveness of its provisions.

The last time America saw this team in action on the Senate floor was a year ago, when they carried the highly controversial Keystone pipeline bill over the finish line. They didn’t agree on its contents and President Obama eventually vetoed it, but that didn’t stop them from working together in a respectful, cooperative, and open manner.

That experience prepared them for the tough work on this bill, the Energy Policy Modernization Act, which they do agree on. The measure could well encounter problems this week in the form of “poison pill” amendments. But from the Keystone bill, they learned “keep going, and keep talking, and no surprises,” Murkowksi told reporters as she headed into the chamber last week.

The two senators practice what they preach. As with a well-maintained pipeline, communication flows between them. On most Wednesdays, they met for breakfast in their offices. Instead of flying back to their home states, they stayed in town during the recent “Snowzilla” weekend, keeping in touch with each other as they prepared the bill for the start of floor debate last week.

Their staffs, too, have put in long hours and logged many miles together, holding joint “listening sessions” with stakeholders around the country, preparing for committee hearings in Washington, and negotiating the details of the bill.

The process allowed wide input, including many amendments from both sides, and resulted in a strong 18-to-4 approval of the bill in committee last July. Even the dissents were bipartisan – two from each side.

“Sometimes we can be cynical about this place and what we can get done. Then, all of a sudden, we have a great opportunity to move something forward.... This is a milestone for the Senate,” Cantwell said of the bill on the floor last week.

Since the last energy bill was signed into law under President George W. Bush, the US has become the globe’s leading producer of oil and gas. The costs of producing solar and wind energy have dropped, and Mr. Obama has pushed aggressively against carbon-producing energy such as coal. But US energy policy – and the nation’s energy infrastructure – have not kept up with these changes.

The new legislation aims to do this by making it easier to export liquefied natural gas, and by removing old mandates, indefinitely renewing the main federal conservation fund, and preparing the electric grid for renewable energy, as well as additional cybersecurity.

The bill also supports greater energy efficiency in the federal and private sectors and promotes alternative fuels including hydro and geothermal energy. Domestic minerals, used in everything from smartphones to windmills, get a boost, too.

As the two senators point out, neither side got all it wanted. Murkowski, from a state rich in fossil fuels, would have welcomed opening some areas of the Outer Continental Shelf to oil and gas exploration.

In her ideal world, Cantwell, a champion of renewable energy, wanted far more robust measures to promote clean energy and reduce greenhouse gases, though individual provisions in the bill support both causes.

Instead, the senators led their members to focus on common ground – just as they have over years of working together on issues.

Outside groups on both sides have criticized aspects of the bill, and the White House has expressed some concerns but no veto threat – to which Murkowski let out a happy “whooo!” when she heard that last week.

Senate leaders from both parties back the bill, which, if it passes, would have to be reconciled with a more partisan House bill that the president opposes.

It may not all be smooth sailing in the Senate this week. Certain amendments, be they efforts to counter the Obama’s coal policies or help the residents of Flint, Mich., with their drinking water, could cause turbulence or potentially sink the legislation.

Still, observers remain hopeful. “I’m optimistic,” says Laura Hall, of the Bipartisan Policy Center think tank in Washington. Murkowski and Cantwell “are working pretty openly to make sure everyone gets in the process.” Bottom line: “They want to get things done.”