One country, two histories: What does it mean to be an American?

Loading...

| BUFFALO, N.Y.; and JACKSONVILLE, FLA.

How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?

During the past two years, that question has flowed through cultural battles over what’s taught in classrooms – particularly relating to history and race.

It popped up when President Donald Trump called for more “patriotic education” and when some educators embraced using the 1619 Project in schools to reframe the traditional U.S. origin story. Also part of the mix: steps taken by dozens of states aimed at limiting instruction related to the concept of critical race theory.

Why We Wrote This

How do you create a sense of shared community when a country’s founding stories are no longer agreed on? Part 2 in a series.

Most schoolchildren already recite the Pledge of Allegiance and learn patriotic songs. But beyond traditional pageantry, many educators are rethinking which topics and voices they should emphasize, trying to reconcile the country’s multicultural roots and its founding principles. The long-standing narrative of U.S. history textbooks, that the country’s overall arc tilts toward progress, is itself under challenge.

“We’ve come to this inflection point in our disagreements about what America is and what it means,” says Jonathan Zimmerman, an education historian at the University of Pennsylvania.

“We’ve always fought about the history curriculum, but I think in prior eras, the fight was really about who should be included in the story; it wasn’t about what should the story be. And that’s the fight now,” says Professor Zimmerman.

A majority of Americans are in favor of teaching “the full history of America – including the terrible things that have happened related to race and racism,” according to a September 2021 report based on a survey of registered U.S. voters. They are more divided on the extent to which racism is a current problem and whether schools should focus more on teaching about it. Beyond that, most also agree that school should teach young people to love their country.

But which version of it? Two approaches to American history that have captured public – and critical – attention recently are best known by their dates. The 1619 Project reframes U.S. history, focusing on slavery and its ongoing legacy. It appeared first in The New York Times, created by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, and went on to win a 2020 Pulitzer Prize for commentary. The 1776 Report, commissioned by Mr. Trump and released in January 2021, and the separate 1776 curriculum – produced by Hillsdale College in Michigan – champion a traditional view of America’s founding.

Visits this spring to classrooms where both approaches are being used offer insights into the differences in what’s highlighted in each – but also show the similarities: extensive discussion, reading and analyzing texts, and expectations for students to contribute to society. Educators at the schools talk about the need to create informed citizens, ready to participate in the work of democracy.

A focus on perspective

As of yet, there’s no national data on how many of the country’s roughly 99,000 K-12 public schools use the 1619 Project or the Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum. The Pulitzer Center in Washington produces K-12 lesson plans for the 1619 Project, available for public download. This school year, individuals from 40 education organizations participated in a 1619 Project network cohort, and a similar number of organizations are expected to participate next school year.

“This project asks students to really consider what is the history of the United States and whose perspective has been presented to you before,” says Fareed Mostoufi, associate director of education at the Pulitzer Center, a nonprofit that supports journalism focused on underreported issues. “We want students, these are our future leaders, making informed decisions and being curious.”

The goal of using the 1619 Project – included in the district’s Emancipation Curriculum – is to empower students of color to know their greatness, says Fatima Morrell, the associate superintendent for culturally and linguistically responsive initiatives at Buffalo Public Schools in New York. It’s also to train students to be informed and critical thinkers who are prepared to live in a democratic society.

“It’s an American ideal to fight for justice for all. Our country was founded on those ideas,” says Dr. Morrell, in a phone interview a month before the May 14 grocery store attack in her city, when a gunman killed 10 Black people. The Emancipation Curriculum, introduced in the 2020-2021 academic year, helps “prevent the Derek Chauvins and George Zimmermans” of the world, she says, referring to the former police officer who murdered George Floyd and the man who killed Florida teen Trayvon Martin.

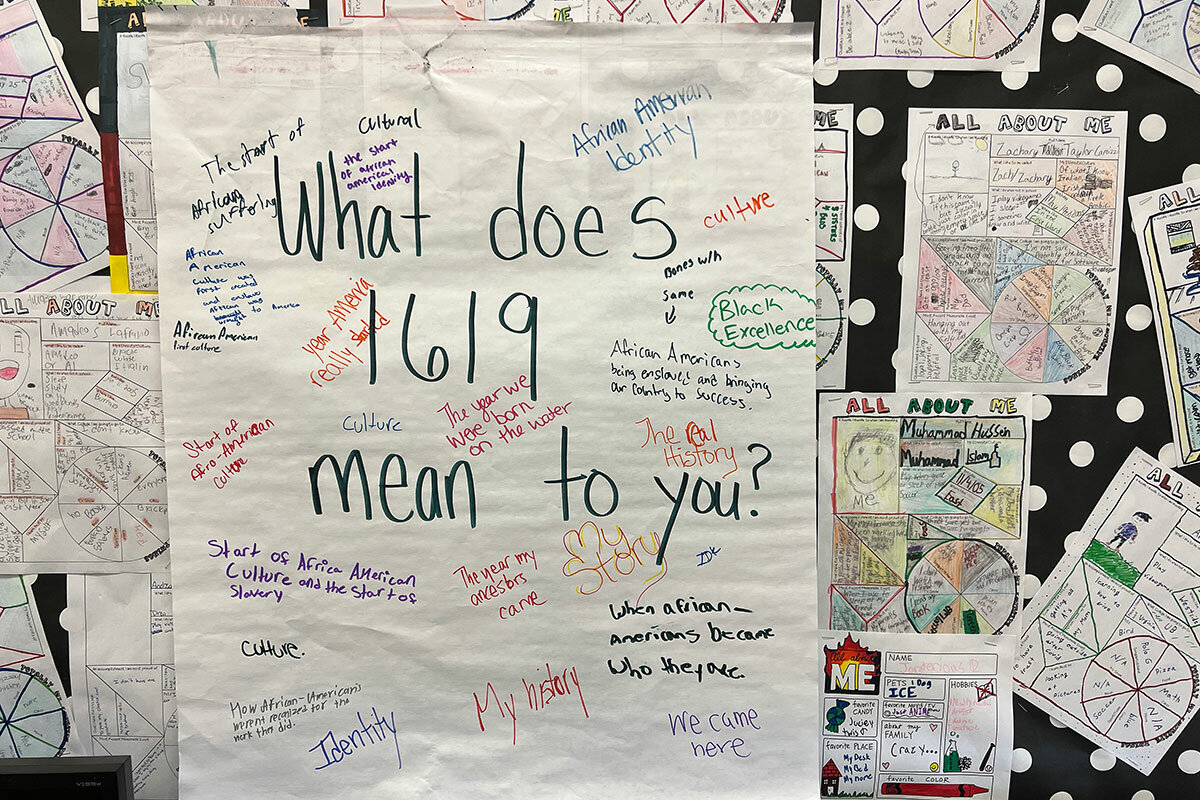

Use of the 1619 Project content in the district engages students in a variety of ways. During the school year, an 11th grade U.S. history class at Lewis J. Bennett School of Innovative Technology #363 read and discussed Ms. Hannah-Jones’ opening 1619 Project essay on democracy, in which she grapples with her view of the American flag.

Large white flip-chart papers still hung on the wall in early May with prompts from the unit and student responses. One question reads, “What does 1619 mean to you?” Student comments include, “African Americans being enslaved and bringing our country to success” and “my history.”

Teacher Genah Lasby sees value in looking at all aspects of U.S. history. “In order to unify, we have to see the problems and issues that have occurred throughout time,” she says. “We all make mistakes, including the United States. And that’s OK, because we can learn from it, we can change, and we can make it better.”

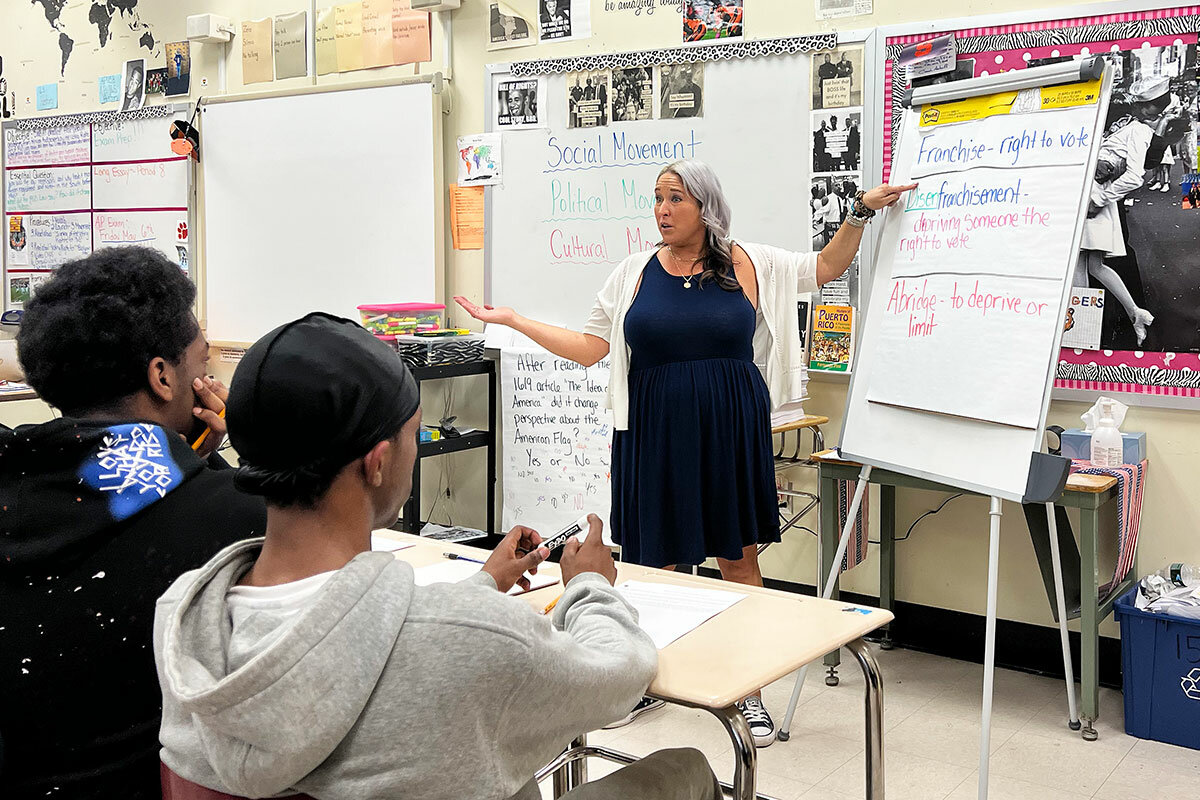

Several miles away, Deborah Bertlesman starts her ninth grade English language arts class at Frederick Law Olmsted #156 by asking students to write about and discuss a quote from one of the essays in the project.

“Slavery gave America a fear of black people and a taste for violent punishment. Both still define our criminal-justice system,” the quote reads, part of lawyer Bryan Stevenson’s essay.

Students also write down information they see in the essay that confirms or challenges the story of American history they’ve already learned. During discussion, some students say they wonder whether the U.S. justice system is backsliding, after they read about some of Mr. Stevenson’s clients picking cotton at a Louisiana prison on the grounds of a former plantation.

Class discussion emphasizes actions students can take and their future impact on society – ideas reflected in posters on the walls with messages like “Tell your story” and “You are powerful.” The school building serves almost 900 students in grades five through 12, of which 68% are students of color. Median household income in the city is just under $40,000.

Chase Wood wants to become a civil rights lawyer. One of her research projects for the class this year was on how Black people interact with the criminal justice system. “I want to be that one peaceful person who goes to fight for people and civil rights,” says Chase.

Ms. Bertlesman ends by asking the class to respond to the prompt, “What is one thing you can do to continue to advocate for justice and change the world for the better?”

She views the 1619 Project as an opportunity to bring up perspectives that weren’t included in schools before, rather than an attack on American values, as some critics have charged. She considers systemic racism to be a truth that students and teachers should have “complex” discussions about, rather than ignore.

“Good citizens criticize. Good citizens question. That’s democratic – that’s democracy if I’ve ever heard of it,” says Ms. Bertlesman, who has not read the 1776 curriculum.

“It’s about giving them the evidence”

The Hillsdale 1776 Curriculum is also available for public download. Hillsdale College runs a network of K-12 classical education schools, which currently includes 57 member and affiliate schools with a mixture of public charter and private schools. The free 1776 resources, including primary documents and lesson plans, are culled from the history curriculum that Hillsdale has offered its schools for more than a decade.

“It’s not about pushing a particular agenda. It’s not about making sure students have access to a specific narrative,” says Kathleen O’Toole, assistant provost for K-12 Education at Hillsdale College. “It’s about giving them the evidence so they can go about learning what happened in American history, and then once they understand what’s happened, and have read the associated documents, then they can make a judgment for themselves about what it means and whether it’s good or bad.”

“We’re not afraid of asking hard questions,” she adds.

Oscar Ortiz is an immigrant from Honduras who is starting Heritage Classical Academy, a Hillsdale public charter school in Houston that expects to open in 2023. He says the history curriculum will help students understand how the ideas of America – like equality, liberty, popular sovereignty, and the rule of law – developed and why they are important.

Students “are going to learn what it means to be [American], what are the ideas or principles that set us apart from the world, and they will never feel that they have to give up their heritage or cultures as they do that,” says Mr. Ortiz.

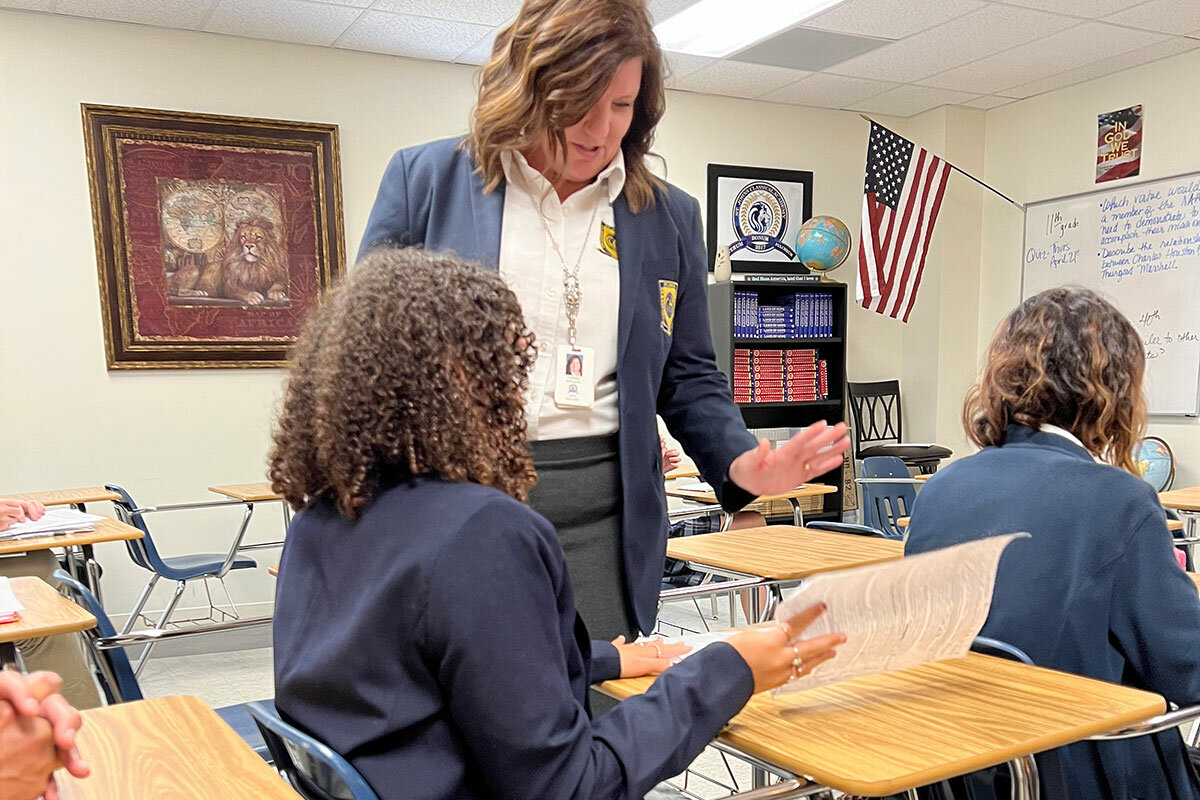

In Florida, students in Hillsdale schools spend half of each school year on American history, from kindergarten on. In April, 11th graders in a U.S. history class at St. Johns Classical Academy, a public charter school in Fleming Island, read aloud from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

Their teacher, Carmen Burgess, poses questions for discussion including, “How should we determine if a law is just? Which virtue is shown in Dr. King’s letter? Which virtues were denied to Dr. King and the other protesters?”

Ms. Burgess wears the same school uniform as her students, a navy blazer with an embroidered school seal. A poster of “In God We Trust” sits under the American flag in her classroom. The hallways are dotted with portraits of Founding Fathers and classic Western art.

The school, which opened in 2017 and awards seats by lottery, educates 800 K-12 students, with over 1,000 more on a waiting list, according to the school headmaster. The school is built on the property of a former church in a suburb of Jacksonville where the median household income is $101,000. The student body is 77% white.

The class talks about Dr. King’s intended audience and what he means when he writes of the feeling of “nobodyness” imposed on Black people by segregation and the different experiences of white and Black people in the 1960s.

“Does this kind of thing happen only in America?” asks Ms. Burgess at the end of class. Her students reply no, and they list other countries with contemporary strife, like Myanmar. She points to the poster of the school’s standards of virtues and encourages students to pick out and practice one.

One of the students, Grace Holton, says she plans to be an aerospace engineer. She expects to vote when she’s 18 and considers her school a place where she’s learning values that she’ll draw on as she eventually participates in U.S. civic life.

“We’re young. This is where you shape yourself for the rest of your life,” Grace says of her school. “At first when we came here, it was like, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re pushing these virtues at us again, can’t they stop, we’re good people!’ But it kind of sticks and then you start noticing this person was really displaying integrity or that person really needs to work on their citizenship.”

Ms. Burgess has not read the 1619 Project and believes media coverage of history debates is divisive. “Anybody can use history to try and prove any point based on a perspective,” she says. “[Americans] really have more that unites us than divides us. We’re not perfect and we talk about that all the time. We clearly have failed from time to time and yet we also have created ways to repair the breaches.”

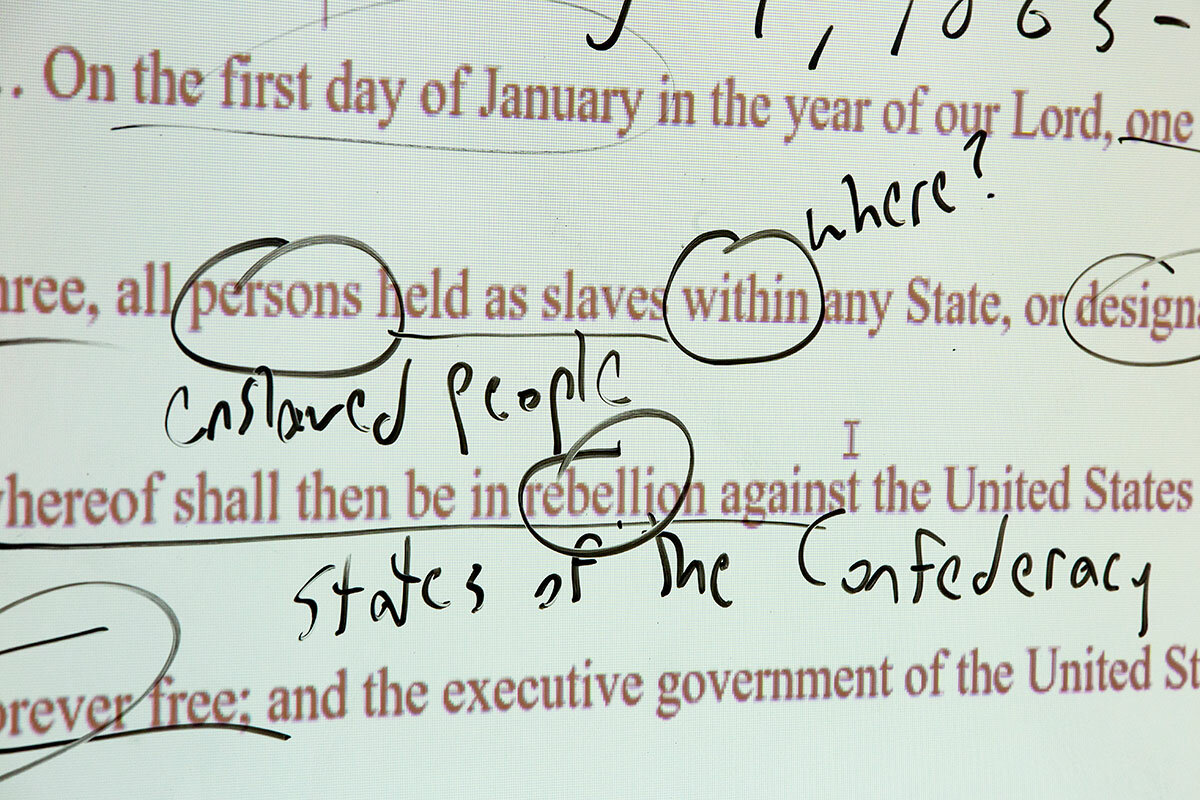

At another Hillsdale network school nearby, Jacksonville Classical Academy, school head David Withun works with seventh graders on a unit of Civil War history, including reading and annotating Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and filling out timelines of key dates.

“The way that I teach ... is as the story of the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. We distill those to things like liberty, equality, republican form of government, and self-government, and the rest of the story is a commentary upon those and a battle over the meaning of them,” says Dr. Withun. The school opened in downtown Jacksonville last academic year. It serves a diverse student body, with about 58% students of color.

Dr. Withun, who wrote a book on W.E.B. DuBois published by Oxford University Press in March, is concerned about a lack of familiarity with history that some of his students arrive with, like one student who thought King was a Civil War abolitionist.

With the school’s approach to teaching, he says, students are able to engage and respond with “‘Here’s why I think that Roger Taney is wrong in the Dred Scott decision ...’ and ‘Here’s why I think Frederick Douglass is right and here’s what Frederick Douglass means to my own life.’ Those sorts of interactions with these really challenging texts inspire the students and help them to think critically about what it means to be an American, what it means to be a citizen, and their place in the larger story of our country.”

“Contested American identity”

Does it matter to American democracy if there are different approaches to teaching students U.S. history?

In a senior education seminar class that he teaches, students read both the 1619 Project and the 1776 Report and analyze how differing interpretations of U.S. history are formed, says Charles Dorn, professor of education history at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine.

“The [public] debate over these two bodies of knowledge brings into sharp relief something that consistently has existed over time in the U.S., which is this contested American identity,” says Professor Dorn, co-author of the 2018 book “Patriotic Education in a Global Age.” “It also suggests ... a fundamental misunderstanding on the part of Americans on what history is,” he says.

All history is interpretation of facts, he says. The assignment he gives students is meant to highlight this.

With a nation as big as the U.S. and its long-standing fragmented education system, “to some degree it’s inevitable” that history won’t always be taught in the same way, says Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute based in Washington, D.C.

Mr. Petrilli says commonality can be found by focusing on the state standards for history and civics instruction. He points to an analysis the Fordham Institute conducted in 2021 of the history and civics standards in all 50 states, which found that the five states with the strongest standards in both areas were a mix of blue and red states.

“They do it in a way that’s patriotic but also critical by getting into the details,” he says, “so it’s doable and that’s what we should aim for.”

The potential for common ground is more robust than partisans on either side might believe.

“When you look at the 1619 materials and 1776, as an educator, parent, if you haven’t completely been sucked into toxic polarization, the heart and mind must go to ‘Isn’t there some room for both/and here?’” says Eric Liu, executive director of the Citizenship and American Identity Program at the Aspen Institute and CEO and co-founder of Citizen University in Seattle. “The fact is, there is more overlap and opportunity for synthesis than one might think between these two.”

This story is the second in a four-part series:

Part 2: How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?

Part 4: How has parental participation in public schools shaped U.S. education?