The South African astronomer who built a pipeline to the stars

Loading...

| Sutherland, South Africa

There aren’t a lot of math problems that stump Thebe Medupe.

As an astrophysicist, he’s wrestled with complex equations for the better part of his adult life. But a decade ago, when he turned his mind to the question of how many black South African students were pursuing astronomy professionally, he realized the numbers just didn’t add up.

Despite scholarships and hype – at the time, South Africa was busy building the Southern Hemisphere’s largest telescope – vanishingly few black students were enrolling in the country’s astrophysics graduate programs. And even fewer were finishing.

At first, Professor Medupe – one of South Africa’s first three black astronomers – wasn’t sure what the problem was. It certainly wasn’t his pitch.

“It’s not hard – I always just tell students there are no words to describe the excitement of discovering something completely new that no one else knows about,” he says, a smile cracking across his face. Or even more to the point: “Astronomy is great fun because you get to work out the secrets of the universe.”

Then it hit him. “We were looking in the wrong places,” he says. The black students in his program came mostly from the country’s well-heeled research universities, places the apartheid government had, until only a few years earlier, reserved almost exclusively for whites. Their manicured quads and colonial-era lecture halls were still dominated by a prep-school groomed elite that few black South Africans were fortunate enough to be born into.

Why not look instead, Medupe reasoned, to historically black universities? Scattered across remote and often impoverished corners of South Africa, they had potentially hundreds of talented math and physics students who might be convinced to take up a life of professional stargazing – if only someone told them it was an option.

“When I was growing up and developing my own love of astronomy, all the books I found were about European scientists and European achievements, and since I didn’t see myself in those books I began to wonder whether it’s true that our people are simply not capable of becoming scientists,” he says. “Well, that’s a big fat lie, of course, but apartheid perpetuated it for a long, long time.”

That history, he knew, was tightly stitched into the present education system. Black universities – purposely malnourished by the former white government – almost never offered a single astronomy class, and most math and physics students were told that their single career option was to become a teacher.

“There are few role models and so talented people turn to other professions,” says Ramotholo Sefako, an astronomer and head of telescope operations for the South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO). He, Medupe, and a third colleague became the first black astrophysics PhDs in the country when they completed their degrees in 2002. Unraveling the legacies of apartheid would take more than simply encouraging more disadvantaged students to apply to Masters programs, Mr. Sefako and Medupe knew. It would require building, from scratch, a pipeline, and then helping students into it.

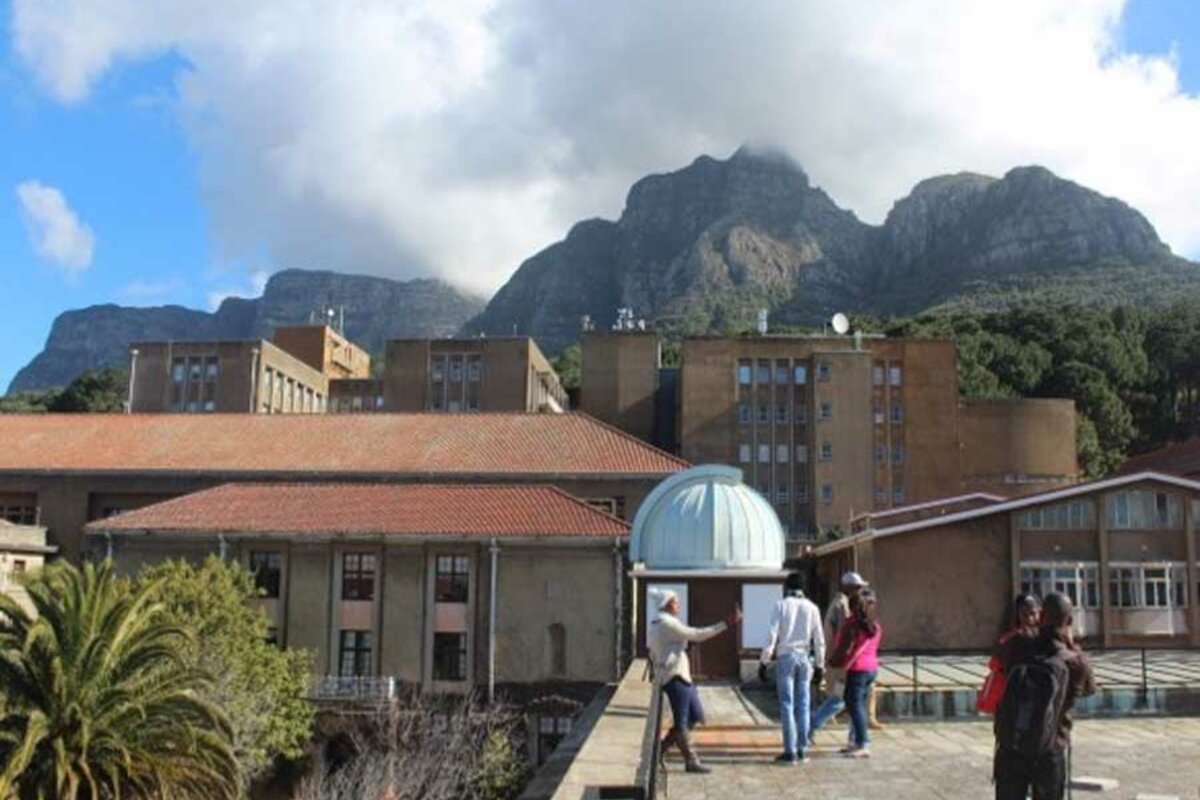

So in 2007, Medupe, working with the National Astrophysics and Space Science Programme (NASSP) – an initiative set up to funnel more South African science students toward astronomy – hatched a plan. They would invite 20 to 30 third-year math and physics students from historically black universities to Cape Town for two weeks during the winter break for a crash course in basic astronomy.

From 2008, those who excelled in the winter school were invited to join a bridging program run by Medupe and astronomer Saalih Allie, now at the UCT Physics Department – a year packed with all the astronomy classes they already would have done, had they gone to a university that offered them. From there, they would complete their honors – an optional fourth year of study offered at South African universities. That, in turn, would open the door for them to pursue a master's degree and PhD through NASSP.

On a recent winter morning, the latest group of those students shuffled through a small museum next door to the South African Large Telescope (or SALT), which sits on a hill just outside the tiny town of Sutherland, in a corner of South Africa so remote that on clear nights the Milky Way arches across the sky in a gauzy ribbon. SALT was the telescope that first helped put South Africa on the global astronomy map, and Medupe takes his winter school students here every year.

“Look at this amazing telescope, you guys,” he says, pointing to a large model of SALT, his voice so excited there seems to be an exclamation point after almost every word. “Do we really want people from overseas making all the discoveries on this? It’s ours.”

For most of the students on the trip, just being here in Sutherland is history-making. Many are the first in their families to go to college, and almost none had been on an airplane before the trip to Cape Town. For nearly all, this trip as far as they’ve ever been from home – literally and imaginatively.

“It’s not like I grew up with a TV to learn all these concepts,” says Siyamthanda Gcelushe, a physics and computer science major at the University of Fort Hare in South Africa’s rural Eastern Cape. Instead, he says, he used to read ahead in his high school physics classes, so excited to master a subject that “teaches you something new about the world everywhere you turn.”

“When Professor Medupe came to our university and explained that it is like this with astronomy, too – that you learn about how stars behave and why, about their colors, their size, their significance – that really captured my mind,” he says. “We never even thought there were people studying this.”

For the students who choose to continue beyond the winter school, Medupe often continues to serve as a mentor, even if he is not directly supervising their work.

“Astronomy is still a very rare profession for black people,” says Phumlani Phakathi, who completed the winter school two years ago and is now finishing an astrophysics honors degree. “Professor Medupe is showing us what’s possible. It’s much easier to preach when you have run the same miles, when you have been in the same shoes.”

But those miles take a long time to run. It is only now that students are beginning to emerge from the other end of the pipeline Medupe fashioned a decade ago. He estimates there are still less than a dozen black African astronomers in South Africa, but a small cadre of his students are now on the brink of finishing their PhDs and beginning their careers as lecturers and research scientists. And more than half the students enrolling in post-graduate astrophysics courses at the University of Cape Town are now black South Africans, he says.

“In the next few years I think we’ll be seeing quite a number of black South African astronomers emerging,” he says. “It’s been slow, but I would say we’re really starting to change the face of this profession.”

Still, there are massive challenges. For instance, there is not a single black South African woman with a PhD in astronomy, though this year’s winter school was about half female.

“You have to put in double the effort to be respected and treated not as a woman, but as a scientist like any other,” says Miya Mathapelo, a physics student at the University of the Free State in QwaQwa, who was among those female students. “A lot of women drop out for that reason.”

Another challenge is shifting the center of gravity in the South African astronomy world, which has historically been set into orbit around UCT and the SAAO, which is also headquartered in Cape Town. To that end, Medupe runs an astronomy program at the University of the Northwest, in his hometown of Mafikeng, in South Africa’s rural North West Province. Recently, the university bought him a research-grade telescope, and he says the program is thriving, proof that astrophysics programs in South Africa can prosper with even modest resources and investment.

This doesn’t surprise him, he says, given his own simple beginnings in the field.

He traces the arc of his professional life back to February 1986, when he watched Halley’s Comet streak past Mafikeng on a summer evening. One day not long after, Medupe, who was then 13, went to a local library and found a book that explained how to construct a homemade telescope using lenses and paper tubes.

“So I got lenses from the school lab and I built this thing and pointed it at the moon,” he says. “Since then, I’ve never looked down.”

Part 1: Want kids to show up to school? Embed a mentor.

Part 2: College supply list for low-income students: Books, financial aid ... a mentor

Part 3: From juvenile detention to straight A's, with the help of a mentor