Louisville's experiment: Can teaching empathy boost math scores?

Loading...

| Louisville, Ky.

At Cane Run Elementary School, ringing bells mark more than the start of the school day.

For teachers Meghann Clem and Christine “Shay” Johnson, the sound of a chime begins another 50-minute lesson to teach students compassion, empathy, mindfulness, and resilience. These so-called soft skills, research suggests and educators believe, will translate into success inside and outside of school.

It’s all part of the Compassionate Schools Project (CSP), an ambitious $11 million, six-year experiment in social and emotional learning in Kentucky's Jefferson County Public Schools.

“We’re going to really try to keep our brains focused on the sound of the bell,” says Ms. Clem to a room of kindergartners sitting cross-legged on mats. “And when you can’t hear the bell anymore, I want you to look up and show me those beautiful smiles.”

Clem strikes a small wooden mallet against a metal chime and waits. Seconds pass in silence as, one by one, students look up, grinning.

Except for Jeremiah, whose forehead was touching the floor. He was fast asleep.

Clem guided his classmates to the next exercise – stomping around the room as if they were climbing up a mountain – and then stopped by Jeremiah’s mat.

She jostled his shoulder gently. Did he want to climb the mountain? He shook his head. Clem steered him to a mat in the corner, where he slept soundly for the rest of the class.

“Normally, I would be like, ‘You need to wake up, you need to sit up, and you need to listen to me,” says Clem, who has taught elementary school for 12 years. “Instead, I’m like, he needs to rest. In that moment, that’s compassion for Jeremiah. He didn’t need to walk around and do the mountain. He needed to rest.”

It’s too soon to say whether this compassion curriculum will translate into academic gains or fewer behavior problems. However, philanthropists were impressed enough by classroom visits to donate an additional $4.4 million to the project this week, boosting the total amount raised to date to $6.5 million. District and CSP officials announced the gifts in a press conference Wednesday morning.

Dr. Patrick Tolan, who directs the University of Virginia's Youth Nex Center to Promote Effective Youth Development, which oversees CSP, says the time that elapses between a good idea and progressively larger rounds of testing to prove the idea works is usually 15 to 17 years. That’s almost an entire generation.

The way to shrink the time from “bench to bedside,” he says, is with a strictly implemented and evaluated program in a real-world setting.

Jefferson County Public Schools was a good fit, researchers found, with its racially and economically diverse student body, and mix of suburban and urban schools in and around Louisville. JCPS Superintendent Donna Hargens was an enthusiastic supporter, and so were city leaders. The CSP experiment comes four years after Louisville Mayor Greg Fisher signed a resolution to add the city to an international coalition of “compassionate” cities committed to the values of selflessness, equity, justice, and respect.

The compassion curriculum, which aligns with state curriculum standards, will replace traditional physical education and practical living courses at 25 schools, while 25 other elementary schools will serve as comparison schools. Tolan hopes to see the same sort of positive outcomes found in other social and emotional learning (SEL) programs.

CSP officials point to a 2008 meta-analysis of 180 school-based SEL programs, which which showed an 11 to 17 percent increase in students’ academic performance and had better problem solving and conflict resolution skills.

A 2015 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found a positive correlation between “kindergarten social competence and future wellness.” In other words, kindergartners who are empathetic and who can regulate their emotions were more likely to graduate from high school on time and less likely to use drugs.

'Compassionate Shay Project'

At Cane Run, which was one of three elementary schools that were part of the pilot program, Clem was CSP’s first teacher. This year, she was joined by Ms. Johnson, who initially wasn’t interested. She was a veteran third-grade teacher and says that initially, she hadn't wanted to switch to what had, on the surface, sounded more like physical education. But after five days of intensive training, two of which were focused solely on the teacher's mental outlook and welfare, she was sold.

Before, Johnson had five minutes in the morning to check in with students. Now, each CSP class, which students take two or three times a week, begins with deep, calming breaths and the focusing exercise of listening to the bell.

Johnson recalled a recent class in which she gave her usual instructions to students: close your eyes, rest your bodies, and give compassion to your bodies through rest.

She heard a boy whimpering. “I go over and check in on him and he tells us, ‘My dad's going to jail tomorrow,’ ” she says. “He was able to tune into what he was feeling right there at the moment.” Johnson moved to comfort the boy.

Johnson left a third-grade class that was “non-stop curriculum” for a project she thinks was custom made for her. She calls it the “Compassionate Shay Project.” Johnson, who has been diagnosed with a chronic condition, finds her own health has improved – a result she says of the soothing music and lower lights in her classroom.

The CSP borrows some language and poses familiar to those who practice yoga, but it avoids that word. Yoga implies a spiritual practice that would be inappropriate in a secular setting, says Alexis Harris, CSP’s on-the-ground project director and a research assistant professor at UVA.

What they do, Dr. Harris says, is mindful movement. It can get noisy.

On a recent Tuesday, Johnson leads students in a chant as they march around their mats. “We’re walking around our mountain and we’re looking for our friends!”

“I see cobras,” Johnson says, as the children fall to the floor in cobra pose, their legs and bellies against the floor as they press their upper body up using their arms. Then, they slither and hiss like snakes before jumping up and marching again. “We’re walking around our mountain and we’re looking for our friends!”

Johnson sees a butterfly and they all sit down, the soles of their feet touching. She tells them to move their knees up and down, as if they were bees en route to a nearby flower.

With a room full of six-year-olds, there’s bound to be some silliness. “I broke my back,” one says. “I broke my leg,” says another.

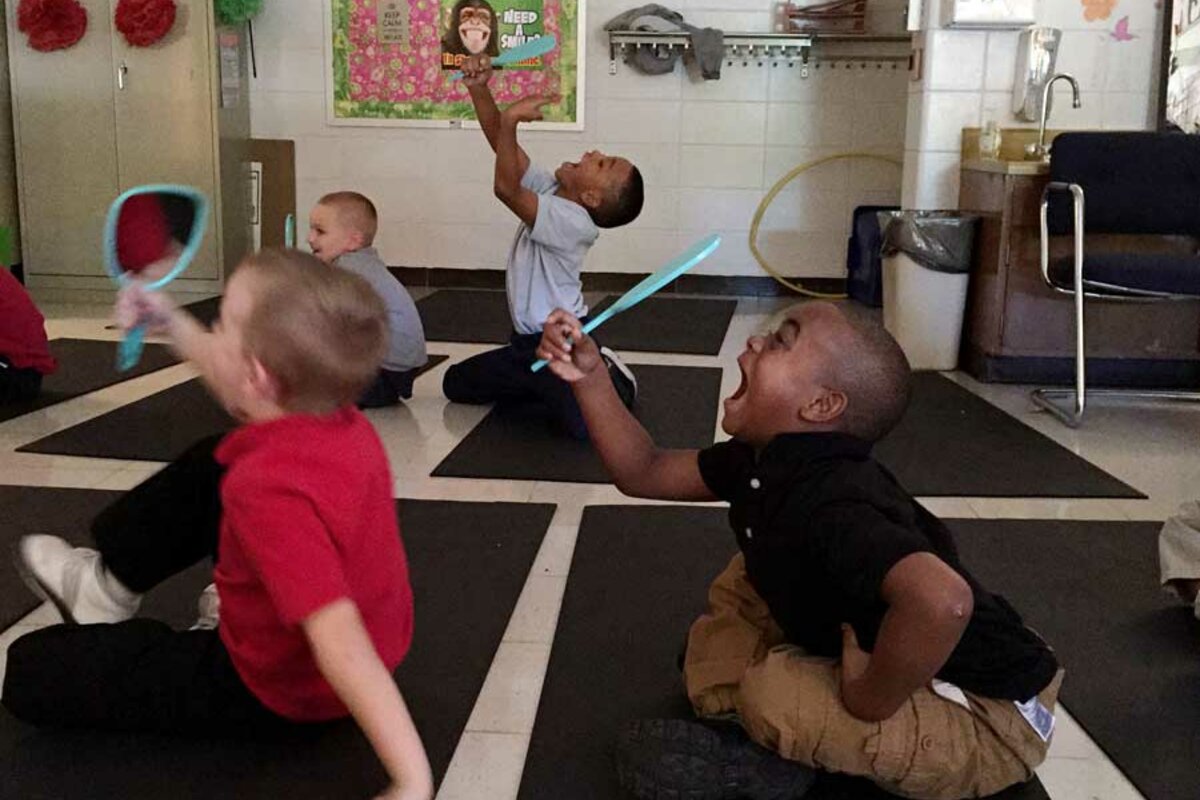

Then Johnson passes out hand mirrors. One of the curriculum’s objectives is for students to recognize the seven universal emotions and to accurately interpret others’ facial expressions.

What if, Johnson wonders out loud, your parents told you’re having pizza and ice cream for dinner? The children squeal and smile (happiness and surprise) as boys in the back of the room open wide, as if they’re preparing to swallow an entire pizza whole.

'Life happens big time to our babies'

Another universal emotion is sadness, which CSP teacher Debbie Hutchinson at Semple Elementary unwittingly tapped into when she asked second-graders to draw their heroes.

“Most of them, either [their heroes] had passed or they were in prison or they don’t see them a lot,” she says.

The exercise turned into a cry session, says Ms. Hutchinson, whose brother-in-law died less than two months ago. The curriculum, she confesses, “is helping me, too.”

This school year alone, eight parents of JCPS students have died at a single school. Accidents and a bad bunch of heroin, Harris explains. “Life happens big time to our babies,” Johnson says.

The day before, Johnson says, at a park about two miles away from Cane Run, a shooting broke out during a youth football practice. Kids hit the ground and no one was injured, but the trauma from that exposure to violence follows the children to school.

It’s no wonder some kids are distracted during class, but before CSP, Clem says, students didn’t always get the help they needed.

“How many times as a teacher have I said, ‘Sit up and focus,’ when I’ve never once given you the definition of what focus means?” Clem says.

Now, she’s showing them what it feels like to focus. Even misbehaving students give their classmates a chance to practice what they’ve learned.

She points to that morning, when one most of the class was sitting obediently, but "I had a kid, during the bell, running across these chairs,” Clem says, pointing to a row of blue chairs lined up against the wall. “But,” she says proudly, “I had 22 kids who were able to sit here and tune him out. Now imagine that in a testing situation.

“They need to be able to stay focused even through major distractions. Everything about this curriculum teaches them how to do that.”

The pause place

Compassion in the classroom bears little resemblance to the hyper-disciplined environment found in many charter schools or the demerits system in some JCPS classrooms.

In compassion classrooms, there’s no time-out chair, only a small mat labeled “Pause Place,” where students are encouraged to go when they are upset or having trouble staying on track, so they can self-regulate their emotions and behavior.

The compassion curriculum makes the same frequently quoted point as Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl: Between stimulus and response, there is a space, or as CSP calls it, a pause.

The goal, Harris says, is to take that pause before they react with some behavior that may or may not be appropriate.

The calming breaths, the mirror exercise, learning to de-escalate conflict and ignore distractions – it’s all a pause.

And that speaks to another universal emotion: fear.

Clem theorizes that many teachers treat students more harshly than needed because they’re afraid. Afraid of what students’ poor performance on high-stakes testing might mean for educators’ jobs. Afraid that the principal will pop into class just when a disruptive student is upending a carefully planned lesson. Or afraid of losing a tight grip on the class, a grip they may maintain through decidedly uncompassionate behavior.

Indeed, in a hallway at Cane Run, a student can be heard screaming at a teacher and the teacher yells right back.

That’s reality, Clem and Johnson acknowledge, and to them, it proves that the compassion curriculum is overdue.

That day in Clem’s class, one boy had the toughest time staying on his mat.

“That would have really bothered me and I would have really zoned in on that, but what I’ve learned through all of this training is to stop scanning for the negative,” she says. Instead of immediately disciplining that boy, she says, “I can find that pause and I can sit in that pause a little longer.”

What might the country look like, the teachers muse, if that pause became routine practice in all schools, communities, politics, and even policing, which has come under intense scrutiny in recent years following dozens of high-profile shootings of black citizens?

“Some day, one of them might be a police officer and one of them might be on the other end of that,” Clem says.

Take the Tulsa, Okla., police officer who shot an unarmed black man last month, Harris says.

“She said she was scared for her life and that’s why she pulled the trigger, but if you can find that pause, that can be life-changing.”