The path of two prisoners of war, from induction in Russia to captivity in Ukraine, was arduous, filled with broken promises, insufficient training, and poor equipment. But having survived, they offer insight into Russia’s brutal, yet effective, battle plan.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Discontent can be unifying, even transformative.

A week ago today in this space, my colleague Amelia Newcomb set the table for a midweek story from Bangladesh on how an interim government there was riding into power on a wave of public anger over economic inequality, bringing hope.

Today we report from Nigeria. A sense of injustice over rising food and transportation costs there – amid government spending many see as self-serving – has long simmered in the streets. It’s growing. A spirit of solidarity and cooperation now overrides old enmities. Like hope, it may prove to be an irrepressible force.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 7 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Eyes on Venezuela: An International Criminal Court prosecutor says the ICC is “actively monitoring the present events” there. Security forces in the Latin American nation launched a crackdown on the opposition after its disputed presidential election.

• Hong Kong convictions: The Court of Final Appeal upholds the convictions of seven of Hong Kong’s most prominent pro-democracy activists over their roles in one of the biggest anti-government protests in 2019.

• Trial begins in reporter’s killing: Jury selection is set to start Aug. 12 for the murder trial of Las Vegas-area politician Robert Telles, who has pleaded not guilty in the September 2022 stabbing death of reporter Jeff German.

• Top Hawaii Democrat loses primary: Hawaii’s House Speaker Scott Saiki loses to Kim Coco Iwamoto, a state Board of Education member from 2006 to 2011 who campaigned on tackling corruption in government, and was the highest-ranking openly transgender person elected in the U.S. at the time.

• Disputed Olympic bronze: U.S. Olympic officials say they will appeal a court ruling that resulted in American gymnast Jordan Chiles being asked to return the bronze medal she won in the Paris Olympics floor exercise.

( 6 min. read )

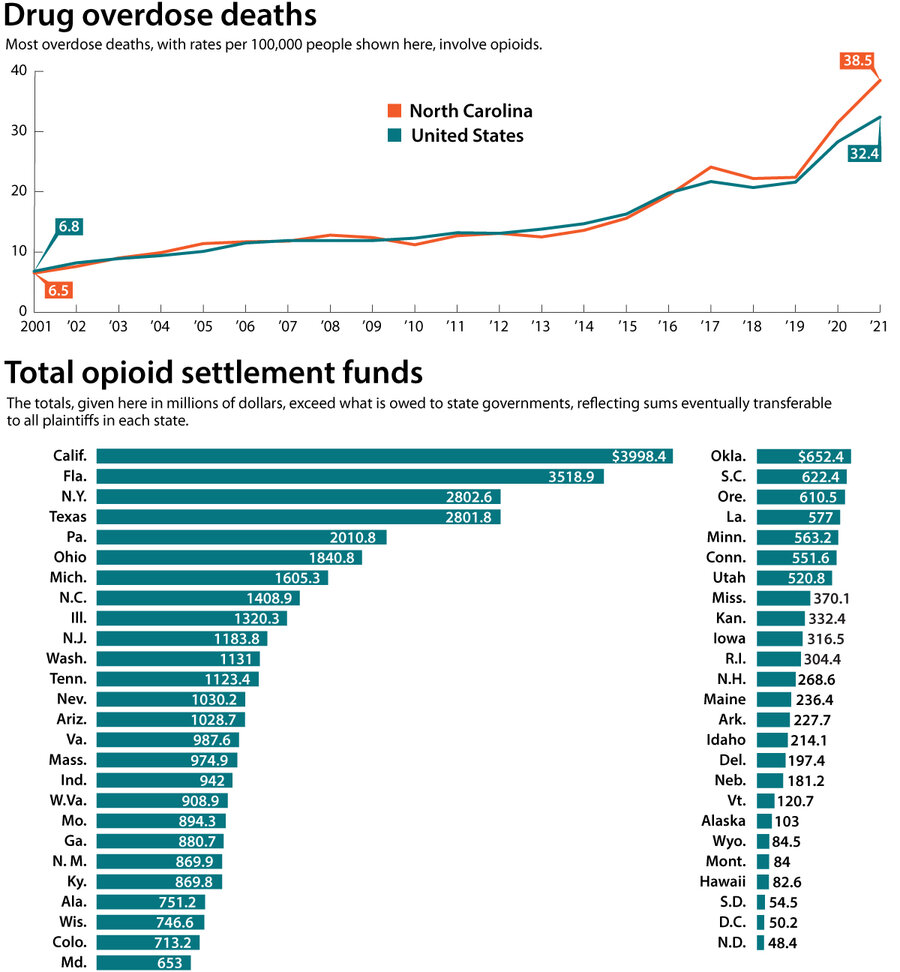

To address America's opioid crisis, health care experts recommend a priority on preventing fatal overdoses in the short term while helping people become sober over time. Money from legal settlements may allow states to do just that.

( 5 min. read )

Recent anti-government protests united Nigerians across religious and ethnic lines. Now the challenge is how to maintain that solidarity.

( 6 min. read )

A bill in Congress would honor 60 diplomats who helped Jews escape the Holocaust. Amid a spike in antisemitism and a growing generational knowledge gap, proponents say it offers a timely reminder of both the atrocities and selfless heroism of that time.

( 4 min. read )

When you’re used to playing the expert, diving into the unknown can be daunting. But as our essayist learns, being a novice can be exhilarating.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

The 2024 Paris Olympics may be over, but one heartwarming video has gone viral on social media. It shows the medal ceremony for the floor exercise of women’s gymnastics. The two Americans, Simone Biles and Jordan Chiles, bow to the gold medal winner, Brazilian Rebeca Andrade, who smiles, raises her hands, and then poses for pictures with the pair and hugs them. [The bronze medal is still in dispute.] The moment was the first time that three Black medalists had ever shared the podium in the sport, and the crowd loved it.

Moments like these at the Olympics create memories of athletes cheering for one another and hugging. Fans mimic this behavior despite being from various countries. In Paris, most stood for the playing of the national anthem of every country that won. They decked themselves out in national attire and partied in the streets.

Three years ago, when COVID-19 delayed and altered the Summer Olympics, these celebrations didn’t happen. Even this year, turmoil from wars, natural disasters, and political shake-ups have turned many people off from each other and made them unwilling to celebrate. Nonetheless, at least 6 million people descended on the French capital for a cool two-week delight in sporting excellence.

There were many firsts at these Games. Gymnast Carlos Yulo was the Philippines’ first male athlete to win Olympic gold. The Caribbean island of Dominica won its first Olympic medal when Thea LaFond won the women’s triple jump. Athletes were celebrated, win, lose, or draw. At the closing ceremony, newly formed friendships of athletes were on display as they stood shoulder to shoulder with renewed spirits.

Three-time shot put gold medal winner Ryan Crouser says the closing ceremony is the best part of the Olympics because it represents the best of every athlete. “Coming together through sport and finding what unites us, competing in a friendly way, and just seeing a unity amongst athletes with so many smiles and so many memories being made” are what make the experience priceless, Mr. Crouser says. “Regardless of how the athlete performed – you have a select few that won a medal – but everyone there is happy to have that Olympic experience.”

With people the world over often at odds, an event like the Olympics shows that competitors can be friends. The Games are not a distraction from daily life. They are a way to lift every person’s life with moments of eternal glory and gratitude.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 1 min. read )

Glimpsing the spiritual nature of existence frees us from downward cycles.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for starting a new week with us. Tomorrow we’ll look at the rash of U.S. election-related deepfake videos being generated by artificial intelligence – and at how to spot them.

Also: “I’m nostalgic for the Games already.” That was Paris-based Peter Ford, our international news editor, at today’s staff meeting. If you feel that way, too, find our complete coverage here.