Recent days have seen false allegations of AI meddling, actual AI meddling, and reports of old-style hacking all involving the U.S. election campaign. Yet so far, this election’s cyberchaos may be less impactful than experts worried.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

Reporters tackle plenty of tough stories daily, striving to bring better understanding to complex and often weighty issues. Today’s stories on artificial intelligence deepfakes and urban tent encampments are just two examples. But there are also moments when a casual tip or simple serendipity reveals a place that brings connection, that gives our world more breadth by making it a little bit smaller.

Ann Scott Tyson shares such a moment in Chengdu, China, when strangers shifted into friends, and the tyranny of the clock melted away. It, too, helps us understand our world just a little bit better.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 6 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Election security conviction: Former Colorado clerk Tina Peters, the first local election official to be charged with a security breach after the 2020 election, has been found guilty by a jury on most charges.

• Abortion on the ballot: Voters in Arizona and Missouri will join Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Nevada, and South Dakota to decide in November whether to add the right to an abortion to their respective state constitutions.

• Greek fires: Firefighters in Greece are battling hundreds of scattered fires, hoping to end the major wildfire that burned into the northern suburbs of Athens, triggering evacuations and leaving at least one person dead.

• Houthi rebels storm U.N. facility: The rebels forced Yemeni United Nations workers to hand over belongings, including documents, furniture, and vehicles.

• Trump returns to X: Former President Donald Trump recounted his assassination attempt and promised the largest deportation in U.S. history in a conversation with the social media platform’s owner, Elon Musk.

( 6 min. read )

California, which has America’s largest homeless population, is taking a harder tack on enforcement – but some cities are pairing that with more support.

( 6 min. read )

The Republican Party has sought to capitalize on voter concerns over record-high illegal immigration during the Biden years. Here we look at the feasibility of a pillar of Donald Trump’s plan for addressing that influx and disincentivizing such crossings.

( 4 min. read )

Our reporter sought to be a fly on the wall during her early morning visit to a Chengdu teahouse. Instead, she found community among strangers.

Points of Progress

( 4 min. read )

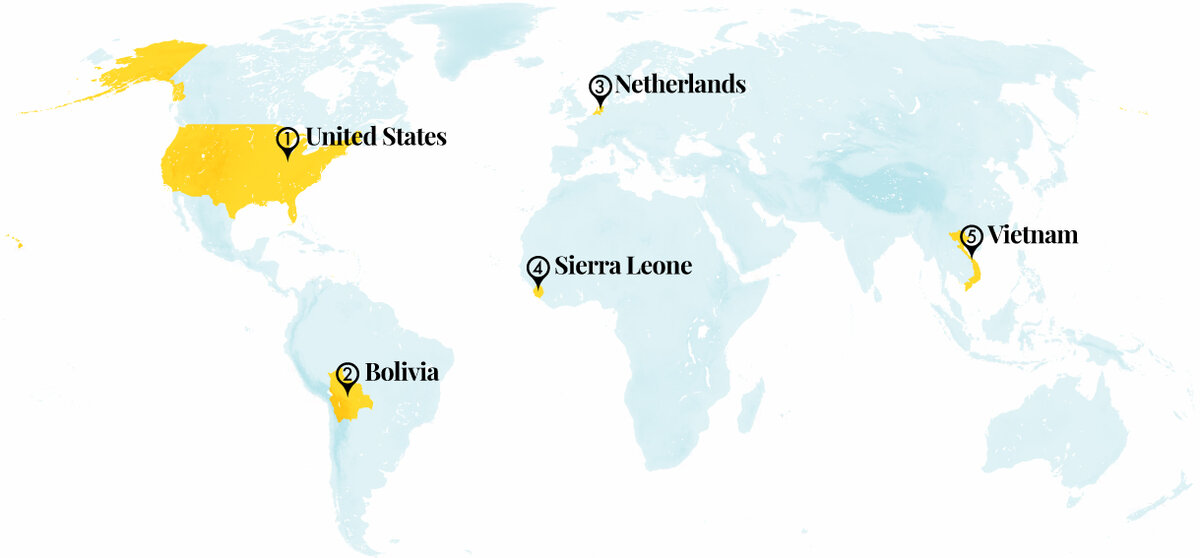

In our progress roundup, a teenager’s opinion on kids appearing in their parents’ videos leads to an Illinois law that says children are workers who deserve pay. And in Sierra Leone, policies around protecting girls and women include a ban on child marriage.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

Last week, some 700 student musicians from 38 countries gathered in New York to celebrate World Orchestra Week. Between rehearsals and concerts, they adorned Carnegie Hall with wishes written on satin ribbons. “Women must have their voice and their dreams,” wrote one from Afghanistan. “May love conquer war,” wrote another from China.

Such words held special resonance for the musicians from Venezuela. While they sought mastery over Shostakovich, their friends and families back home were seeking freedom from a dictatorship that rigs elections to stay in power.

After the July 28 election, President Nicolás Maduro quickly claimed victory even though the National Electoral Council still has not released the official results. Since then, security forces have arrested more than 2,000 people on vague charges. Opposition leaders remain in hiding.

Observers say Mr. Maduro’s longevity in power depends on maintaining the loyalty of key institutions such as the military and courts. One test will come when the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, Venezuela’s highest court, renders a final ruling on the results.

The opposition, meanwhile, is relying on something it hopes will be more persuasive: the truth. It placed election observers in every polling station to obtain and publish official results as soon as they were tallied. The result shows that the main opposition candidate, Edmundo González Urrutia, won nearly 70% of the vote.

Mr. González and other members of the opposition have called on Venezuelans to join in mass protests for the “truth” on Aug. 17. “Demanding respect for our constitution is not a crime, demonstrating peacefully to uphold the will of millions of Venezuelans is not a crime,” he wrote in a statement posted on the social media platform X.

That appeal relies on Venezuelans coming together as one to realize the power of truth to defeat a lie. As the student musicians in New York displayed, the truest pitch of Venezuelan democracy lies in the harmony of its citizens.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

An understanding that God provides all we truly need enables us to experience that goodness more fully in our lives.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, you can read about a court that Liberia is creating to try perpetrators of violence. And have you ever heard of “stunt journalism”? It emerged in the 1800s. We’ll introduce you to one of its modern practitioners.