American forestry has been a stage of conflict between timber interests and conservation. A new generation of ecological foresters wants both to flourish.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

Our in-depth lead story today introduces you to two professionals who represent a shift in thinking about an essential ecosystem. As Weekly Editor Noelle Swan notes, “Where foresters of the past focused on sustaining tree populations to ensure future harvests, this new generation of ecological foresters looks to nurture the vast web of plants and wildlife that make up an ecosystem.”

We’re not talking either/or outlooks; just look at the story’s headline. The focus is on better understanding what makes forests thrive. So I hope you’ll take a refreshing walk in the woods with writer Richard Mertens.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

A deeper look

( 16 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Health insurance and DACA: A group of Republican-led states filed a lawsuit Aug. 8 seeking to block the Biden administration from allowing up to 200,000 participants in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program to access federally run health insurance.

• Thai reformists: Just two days after being disbanded by court order, Thailand’s main progressive Move Forward Party has regrouped under a new name of the People’s – or Prachachon – Party.

• Waiting periods: Maine gun retailers are now requiring a three-day wait for purchases under a new law adopted after the state’s deadliest mass shooting in October 2023. Maine joins a dozen other U.S. states with similar laws.

• 3D-printed neighborhood: A printer more than 45 feet wide and weighing 4.75 tons is finishing the last few of 100 3D-printed houses in Wolf Ranch, a community in Georgetown, Texas, about 30 miles from Austin.

• Perseid meteor shower: The shower reaches its peak early Aug. 12. Astronomers say it’s one of the brightest and most easily visible showers of the year. This year’s peak activity coincides with a moon that is 44% full.

( 5 min. read )

This fall, both U.S. political parties will be seeking any edge in voter turnout that they can get. For Democrats, the new Harris-Walz ticket is energizing an important demographic – young people – as our reporter learned at a rally this week.

( 7 min. read )

Resegregation has become a big problem across the U.S. Parents and educators in one Mississippi Delta town are building barns, planting gardens, and coming out of retirement to help their public schools.

( 5 min. read )

Amid high unemployment and higher-education scandals, young Indians are questioning traditional, merit-based paths to prosperity. And after protests rooted in similar issues came to a head in Bangladesh, some wonder: Could the same happen here?

Essay

( 6 min. read )

Our reporter at the 2024 Olympics stayed upright through some hard-charging days, but also fell hard for host city Paris. We’ll let him tell you all about it – in this first-person report and on a podcast episode that we’ve embedded.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

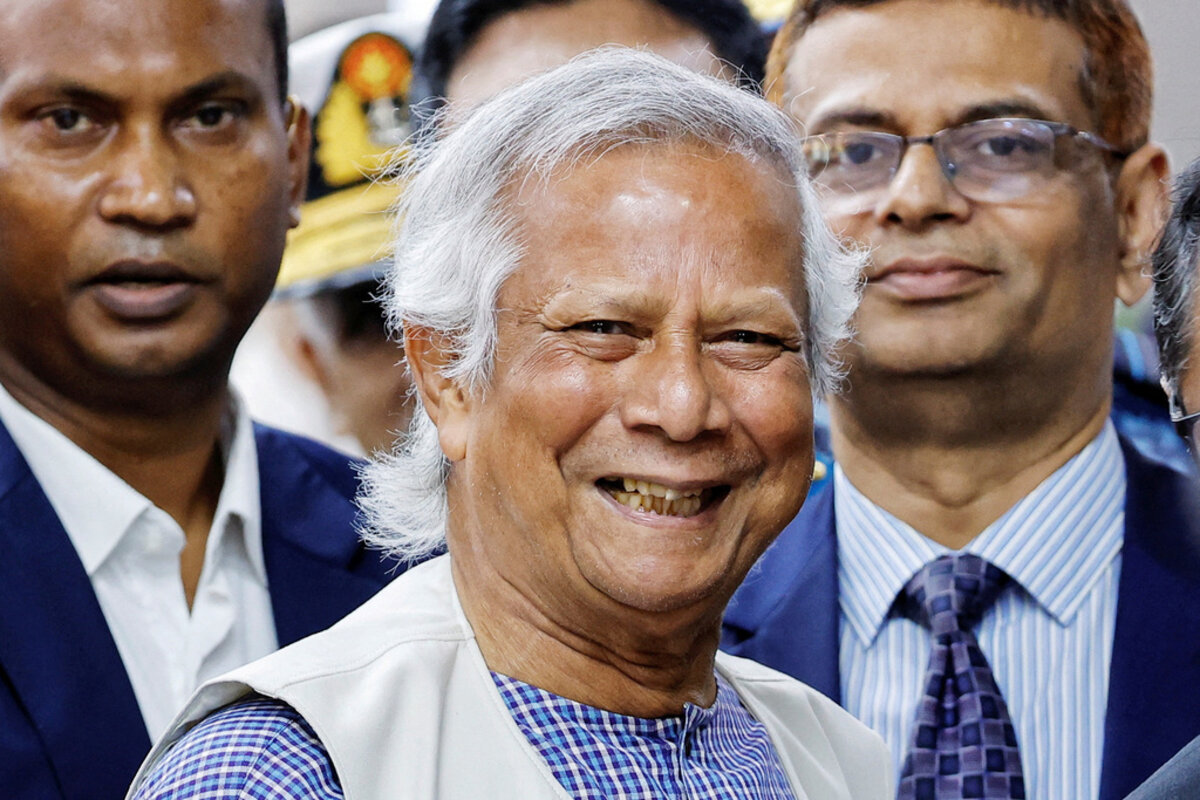

In just four days, two groups in Bangladesh – student protesters and the army – have pulled off something remarkable in the South Asian nation. They forced a longtime autocrat to flee and ushered in a broadly accepted transitional government. What happens now depends in part on a man chosen to restore democracy: Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus.

He got off to a good start by pleading for an end to all violence and putting together a diverse interim Cabinet. If he can provide a quick path to credible elections, he will have laid the groundwork for an inclusive, secular rule in a region lacking models of healthy democracy.

An innovator in antipoverty approaches, Dr. Yunus argued that a stable democracy depends on creating grassroots entrepreneurs. Fifty years ago, as a young professor of economics, Dr. Yunus launched a bank to lift people out of deep poverty through small loans given on patient terms. Since 1974, the Grameen (meaning “Village”) Bank project has disbursed close to $40 billion in loans, often as small as $100, to nearly 11 million borrowers. The bank operates in almost every village of Bangladesh. Borrowers become co-owners of the bank. Nearly all are women. Their default rate is negligible.

In his Nobel acceptance speech in 2006, Dr. Yunus said societies should be structured to “make room for the blossoming” of the “limitless ... qualities and capabilities” inherent in each individual.

“A human being is born into this world fully equipped not only to take care of him or herself, but also to contribute to enlarging the well-being of the world as a whole,” he said. Too many antipoverty programs “[underestimate] human capacity,” he said. They fail “at the conceptual level, rather than any lack of capability on the part of people.”

Little wonder he was the consensus choice as interim leader. Politics, he said, must now stop being backward-looking and score-settling. It must rely on a new generation focused on the future.

After 15 years of corrupt and autocratic rule, Bangladeshis are ready to take a cue from someone who knows how to build the kind of trust predicated on the inherent dignity and capacity of each individual.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 1 min. read )

In times of trouble, and anytime, we can rely on God to keep us safe and secure.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. On Monday, staff writer Scott Peterson, who’s just back from Ukraine, offers rare insight on Russia’s side of the front lines as he shares a deeply affecting conversation with two Russian prisoners of war.