Pageantry and sport do not guarantee global good feeling. But in tough times in the past, the ideals of the Olympics have helped buoy a weary world. Could it happen again in Paris?

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

What’s it like to be in the room at a key moment in politics?

You had a ringside seat when Monitor staffer Sophie Hills wrote about traveling with U.S. President Joe Biden immediately after his June 27 debate upended the presidential race. And you have another today. Washington Bureau Chief Linda Feldmann was one of only three members of the “restricted press pool” allowed in the Oval Office last night as the president addressed Americans about his decision not to seek a second term. You’ll get details that would have not been apparent from the TV feed – the crowd in the room, the reach of one of them for another’s supportive hand. I hope you’ll enjoy the read.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 6 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Climate activists disrupt flights: Germany’s busiest airport cancels more than 100 flights as environmental activists launch a coordinated effort to disrupt air travel across Europe to highlight the climate change threat.

• Melania Trump memoir: Former first lady Melania Trump has a memoir coming out this fall, “Melania,” billed as “a powerful and inspiring story of a woman who has carved her own path, overcome adversity and defined personal excellence.”

• Southwest to assign seats: Southwest Airlines plans to drop its tradition of more than 50 years and start assigning seats and selling premium seating for customers who want more legroom.

( 4 min. read )

Every four years an Olympic host city participates in a ritual of perseverance – with locals and tourists valiantly navigating their environs. In Paris, how has a focus on sustainability affected venue locations?

( 4 min. read )

The room was crowded, but President Joe Biden’s tone was quiet and solemn. His address to the nation sealed his historic exit from the presidential race, while describing the coming election as vital for democracy.

( 4 min. read )

Joe Biden’s withdrawal from the presidential race marks the end of an era. He is the last U.S. leader to believe so viscerally in America’s vision of its central place in the world.

( 8 min. read )

In an election that could come down to a handful of battlegrounds, a running mate who could deliver their home state would be of enormous value.

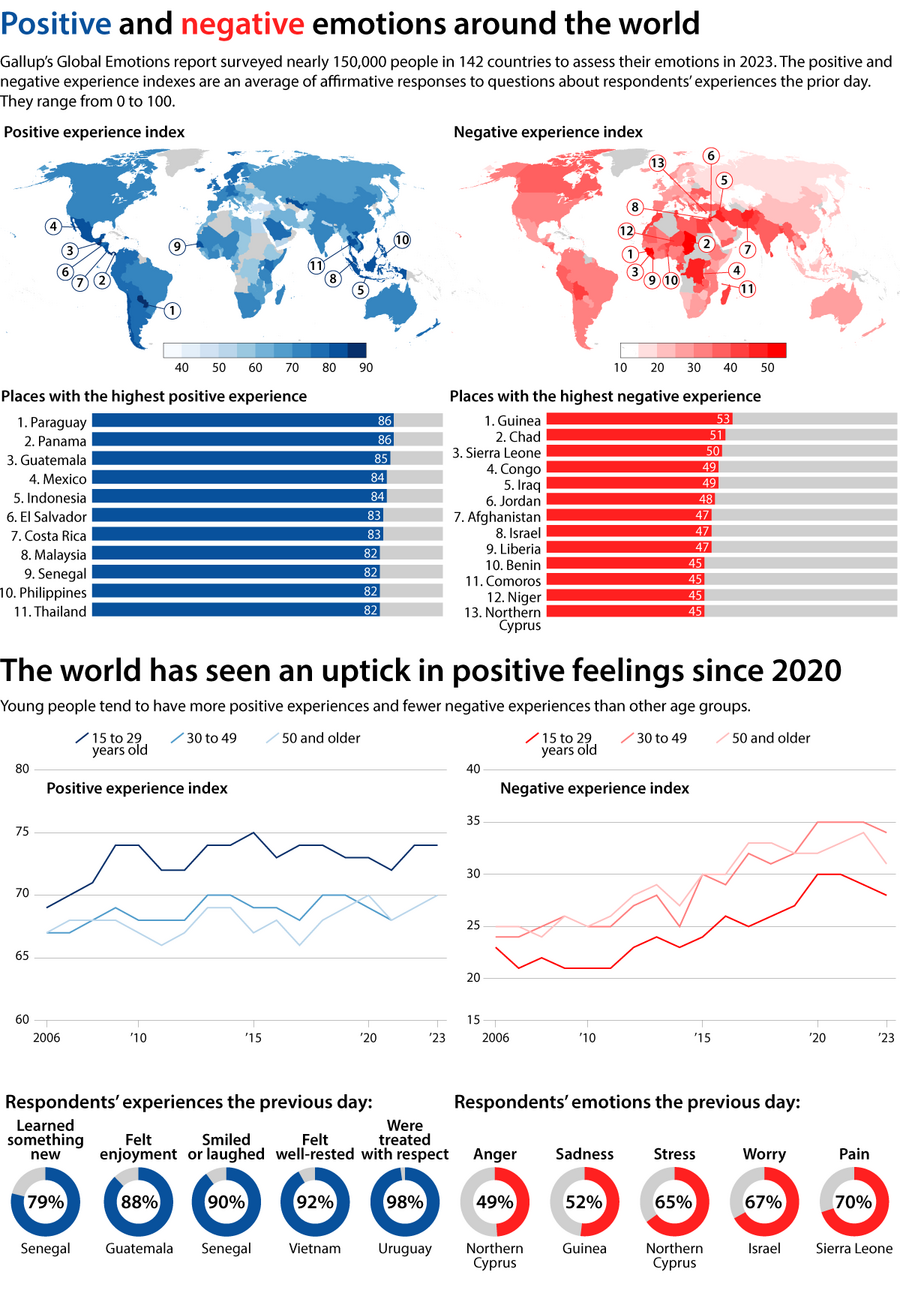

Graphic

( 2 min. read )

Despite what feels like a constant flow of bad news these days, a majority around the world say they feel well rested and joyful. And young people are the most positive of all.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

It may be the world’s worst hunger crisis. And the world’s largest displacement of civilians fleeing war. Yet in Africa’s third-largest country, Sudan, a 15-month-old conflict between two rival militaries has become something else.

It has become a model of how everyday people who were once strangers to each other can bond and band together during a war to build the kind of society they want after a war.

A key fact illustrates the point: Sudanese families have opened their homes to more than half of the people displaced by the war, according to the International Organization for Migration.

These host families have several reasons to provide food, shelter, and comfort to others who may be of different religions or ethnicities. For one, the front lines of the war keep moving, so anyone could suddenly be forced to flee.

Two, Sudan has a strong tradition – reflected in the Arabic word nafeer (meaning “a call to come together”) – of organizing local, voluntary responses to urgent needs, whether they be a harvest or a flood.

“We feel that any person in Sudan can go through this humiliation, so solidarity is our duty in order to relieve each other,” one man told The New Humanitarian after opening his home to 40 people across six families.

Yet thirdly, Sudan has a new tradition that began during a popular uprising in 2019 that ousted a dictator but later led to the current military conflict.

Local pro-democracy groups that led the protests have repurposed themselves into youth-driven “emergency response rooms.” They provide charity kitchens, alternative schools, and other services for displaced people.

These activists are doing more than humanitarian work. They are “working towards a vision of Sudan that is peaceful, just and equitable,” wrote Michelle D’Arcy, Sudan country director for Norwegian People’s Aid.

In the midst of war, these groups are creating “the kind of governance – democratic, equitable, people-centered – that Sudanese communities have long craved,” said Samantha Power, the U.S. Agency for International Development’s administrator.

The war may soon end – peace talks are planned for mid-August in Switzerland. But Sudan’s democratic spirit and nafeer mobilization are already laying the groundwork for peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 2 min. read )

As the 2024 Summer Olympics open and the world celebrates fantastic athletic feats, we can elevate our approach to spectatorship (or participation) by watching for how God is being expressed in the events.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when Patrik Jonsson offers a portrait of Butler, Pennsylvania, which not only witnessed a sobering assassination attempt but also symbolizes the fears and hopes common across small-town America.