Biden’s pullout marks the end of an American era

Loading...

| London

For America, it was a passing of the torch. But for world leaders, Joe Biden’s decision to end his reelection campaign signaled something even more profound.

It is the passing of an era.

Mr. Biden is the last in a long line of U.S. presidents viscerally wedded to America’s post-World War II vision of itself and its place in the world: as architect, leader, and linchpin in a web of alliances dedicated to promoting and protecting democratic friends over autocratic rivals.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onJoe Biden’s withdrawal from the presidential race marks the end of an era. He is the last U.S. leader to believe so viscerally in America’s vision of its central place in the world.

Key U.S. allies – above all, Ukraine – know that the real-world impact of Mr. Biden’s departure from office will still depend on who wins in November.

Donald Trump has shown disdain for the vision of American leadership – rooted not just in power and self-interest but also in values – put in place after the world war, and for the overseas alliances forged along the way.

Kamala Harris, Mr. Biden’s vice president and now Democratic candidate for the presidency, has stood shoulder to shoulder with her boss on Ukraine. She is likely to stay broadly on the path he has charted over the past four years.

Yet the continued commitment to Ukraine that Ms. Harris feels, along with many fellow Democrats and some Republicans, comes from a different place than Mr. Biden’s.

It has been shaped by a very different world, one in which politicians from both major parties have increasingly come to recognize the practical limits of America’s ability to deploy its resources, reach, and power overseas.

And it comes from a different age.

Mr. Biden, born in 1942, grew up in an America whose idea of itself was shaped by Washington’s extraordinary vision of U.S. leadership after the world war.

Despite the postwar impulse of many Americans to retreat from the world – as one top U.S. diplomat put it at the time, to “go to the movies and drink Coke” – the United States extended billions of dollars in Marshall Plan aid to the battered economies of Western Europe, formed the transatlantic NATO defense pact, and championed its support for free nations, free-market economies, and free trade worldwide as the best way to “contain” Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union.

In the decades since, U.S. foreign policy has not always matched that lofty vision.

America has allied itself not just with democrats but with dictators, too. It has fought wars – Vietnam in the 1960s and ’70s, Afghanistan after 9/11, and Iraq in the early 2000s – that caused huge casualties and ended in chaotic retreats.

But the ideal – the assumption that America had a special role in the world and a responsibility toward its allies and the world – was the North Star for American politicians who came of age politically in the postwar years.

Even the younger ones.

John F. Kennedy is remembered for a 1961 inaugural address urging citizens to rededicate themselves to moving America forward. But at its core, his speech was about America’s special postwar place in the world.

“The torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans,” he declared, “born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace.” They would be “unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed” – whether at home or “around the world.”

This expansive view of American leadership, and the sense that it was key to defining what America is, has been an article of faith for Mr. Biden. It was critical in his response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Other presidents might well have opposed Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked assault on a neighboring state. They might well have responded with U.S. sanctions and urged allies to follow suit.

That was pretty much the approach taken by then-President Barack Obama, a child of the 1960s, to Mr. Putin’s first attack on Ukraine and annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Mr. Biden’s response has been of a completely different order.

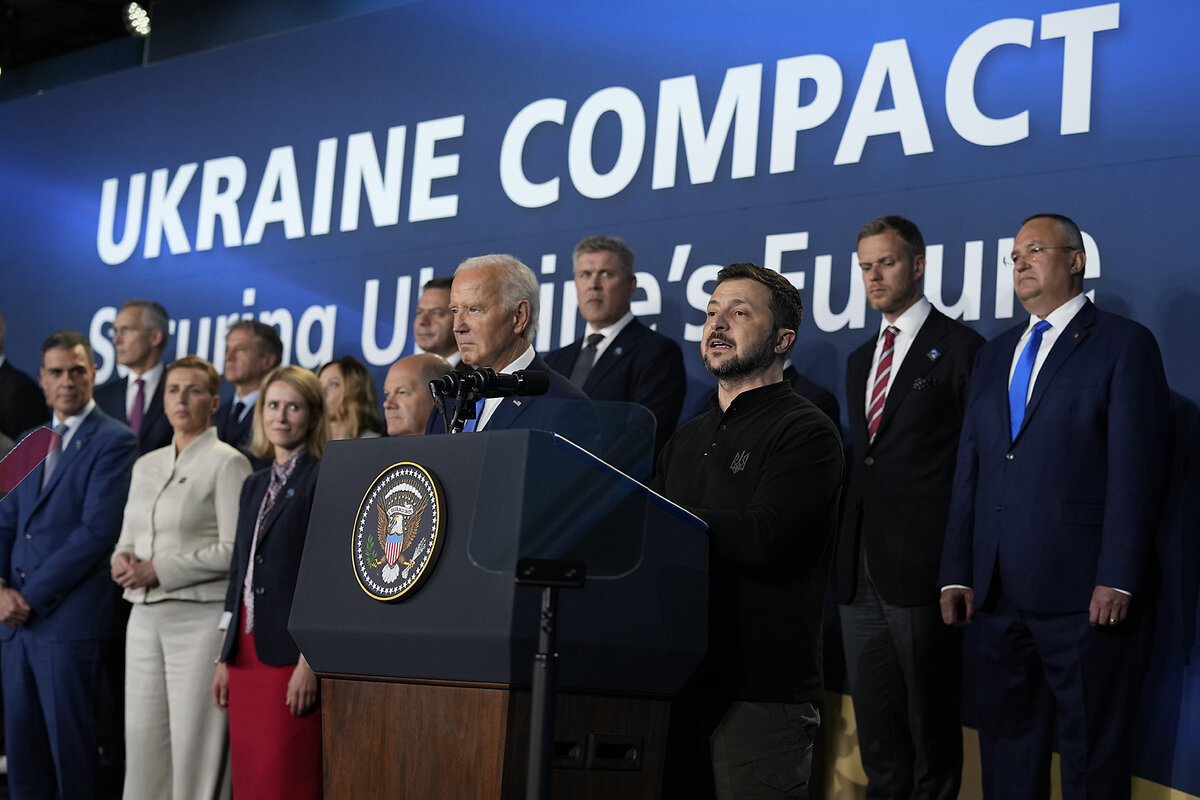

He brought to bear the full weight of his office in assembling and leading key allies, in Europe and beyond, in providing sustained financial and military support for Ukraine’s fighting forces.

The closest recent parallel also came under a U.S. leader whose view of America was forged by the world war: Republican President George H.W. Bush’s response to Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s attempted annexation of Kuwait in 1990.

Mr. Bush, who fought in the world war, took a similarly personal lead in assembling a coalition of some 30 countries, including Middle East rivals, behind a U.S.-led invasion to dislodge the Iraqis six months later.

It’s not yet clear how long and how assertively America will hold to Mr. Biden’s pledge to back Ukraine for “as long as it takes” once he has left office.

But Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, one of dozens of leaders to pay tribute to Mr. Biden after his decision, made clear his understanding of the president’s indispensable personal role in helping Kyiv fight back.

“We sincerely hope that America’s continued strong leadership will prevent Russian evil from succeeding or allowing its aggression to pay off,” he said.