For Democrats, President Joe Biden’s poor performance in Thursday’s debate has resurfaced questions of whether he’s truly the party’s best candidate to beat Donald Trump. But getting him to step aside isn’t simple and carries its own risks.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

Today was, without qualification, a “big news day.”

That’s the kind in which text messages fly, writers and editors huddle over angles, and story lineups change. How best to follow up on what looks to be a highly consequential presidential debate? How best to surface the central considerations of three consequential high court decisions on a tight deadline?

Our answers to those questions start with the expertise of the Monitor’s U.S. Supreme Court-watchers and political writers, grounded in unwavering commitment to context and fairness – and to adding light over heat. You’ll find those stories below. And don’t forget to check out our audio and graphics offerings, along with a captivating feature from the mountainous regions of rural Tunisia.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Gaza City raid: Israel ordered Palestinians to move south amid fighting in Rafah, in what Israel says are the final stages of an operation against Hamas militants there.

• Bible in public schools: Oklahoma’s Department of Education ordered every teacher in the state to have a Bible in their classroom and to teach from it.

• Iranians vote: They are choosing a new president June 28 from a tightly controlled group of candidates. This follows the death of Ebrahim Raisi in a helicopter crash.

• Mongolian elections: A parliamentary election will be held June 28 for the first time since the body was expanded to 126 seats, adding uncertainty to a system that has been monopolized by two political parties and beset by corruption.

• French polls: This weekend brings the first round of snap parliamentary elections that could see France’s first far-right government since World War II.

( 10 min. read )

The three Supreme Court decisions issued Friday alone would qualify as a history-making term. And the court is not yet done, with arguably the biggest case coming Monday.

( 13 min. read )

A year ago, the U.S. Supreme Court barred affirmative action in college admissions. Students have since used their application essays as a place to explore identity.

Podcast

A big city. A big drop in murders. Our reporter wanted to know why.

A credible counternarrative on crime is worth probing. It can undercut misperceptions, including ones promoted for political purposes. It can suggest reasons for progress. It can validate community action. We found one such story in our Boston backyard.

Can Trust Cool a Murder Rate?

( 4 min. read )

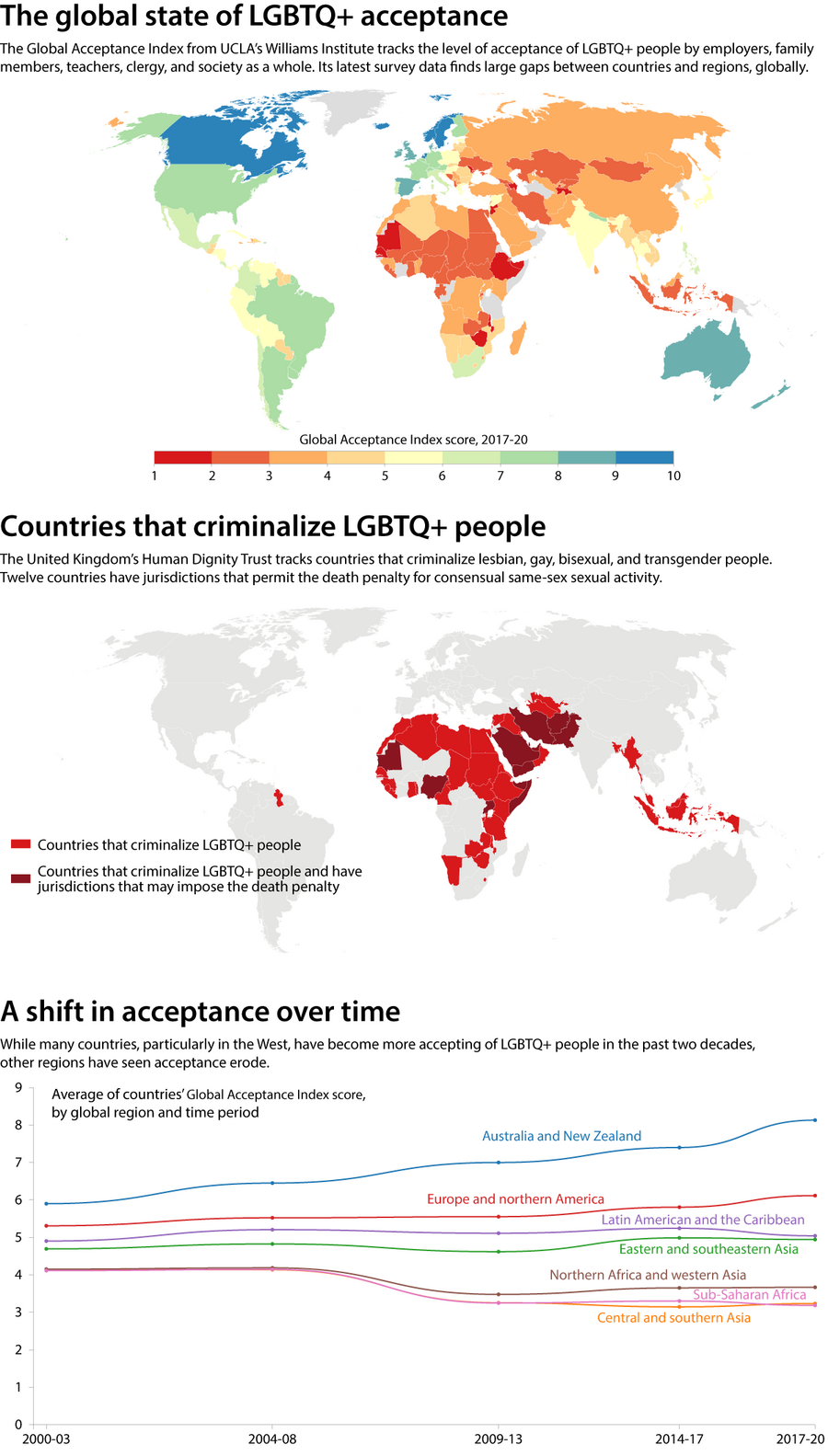

Tracking global LGBTQ+ rights is a complicated endeavor. The community continues to face diverse challenges, but overall, data shows a story of gradual, hard-won progress.

( 6 min. read )

In rural Tunisia, limited government resources can leave people feeling isolated. Karim Arfa reconnects communities by erecting bridges and other vital infrastructure.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

Leaders of the Democratic Party are now debating whether to ask U.S. President Joe Biden not to run again based on his performance in Thursday night’s debate with Donald Trump. They are correct in one respect. Asking him is preferable to forcing his exit, if that is what the party seeks. Yet they can also take a cue from Jill Biden. Last year, the first lady hinted that her husband has options other than being president.

“It’s Joe’s decision,” she told CNN. “And we support whatever he wants to do. If he’s in, we’re there.”

The idea of not setting limits on Mr. Biden’s future reminds us of the late actor Glenda Jackson. After decades of working in film and theater, she went on to a successful career as a politician, only to return to the theater at age 82 playing King Lear on Broadway for eight shows a week. When asked by The New York Times if she feared getting older, she replied, “The essential you is on the inside, it stays the same.”

As the average life span has risen, views have expanded about the potential of older people to keep contributing. “We’ve added a couple of decades, essentially an entire generation, onto our lives, and we haven’t, kind of, socio-culturally figured out how to handle that,” geriatrician Louise Aronson told CBS News.

Dr. Aronson believes public anxiety about aging leaders reflects a fear of aging itself. She suggested in a Wall Street Journal column that people should instead “create the kind of world we want to be old in, one of opportunities and recognition of competence at all stages of life.”

Mr. Biden may decide to stay in the race, as is very possible in coming days and weeks. But if he does bow out as a candidate, it need not be a retirement but rather a “rewirement.” When George Washington stepped down as military commander in 1783 at age 51, he thought of himself as “gray” and “almost blind.” Yet he went on to be president for two terms. Then at age 66, he agreed to serve in the military again, Maurizio Valsania, a history professor at the University of Turin, wrote for The Conversation.

Had Mr. Biden lived in that age, stated Dr. Valsania, “his value would have likely outweighed his deficits in the eyes” of a country that was “aware of the wisdom that certain old leaders could still provide.” Such wisdom need not be confined to the curved walls of the Oval Office.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 1 min. read )

If we’re feeling irrevocably stuck on our path to progress, we can open our hearts to God’s powerful goodness, which leads us forward.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us this week. We have a bonus read for you today from Gambia, which is grappling with how to care for its elders. I hope you’ll check it out!