Respect between citizens and police is critical to society. One police department is showing how better relationships ward off trouble. Since it began rebuilding trust, crime has been cut in half.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

Communication and humanity aren’t words people typically mention first when they talk about policing in the United States.

But those concepts are very much present in our twinned stories that lead today’s Daily. Why? Because more police see them as central to effectiveness. Patrik Jonsson points to a three-city study showing a 14% drop in crime in troubled areas where police officers got training in better interactions. Meanwhile, Troy Aidan Sambajon homes in on Boston, which has just seen the biggest drop in murders of any major U.S. city. A central focus in the city is community policing.

Trust remains an issue. But thinking – and actions – are shifting.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 8 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Israeli strikes in Rafah: Renewed Israeli shelling and strikes have killed at least 37 people, most of them sheltering in tents, outside the southern Gaza city of Rafah. The bombardment hit the same area where Israeli strikes triggered a deadly fire in a camp for displaced Palestinians days earlier, killing 45 people.

• Haiti’s new leader: Haiti’s transition council taps former Prime Minister Garry Conille, who briefly led the country over a decade ago, to return to the role as the Caribbean nation works to restore stability and take back control from violent gangs.

• Russian hacking rises: Disruptive digital attacks, many of which have been traced to Russia-backed groups, have doubled in the European Union in recent months, according to the EU’s top cybersecurity official.

• Israel captures key corridor: Israel’s military says it has seized control of the entire length of Gaza’s border with Egypt.

( 5 min. read )

Boston has been a pioneer of community policing. That’s showing signs of success. The next step is to build a deeper sense of trust with residents.

( 6 min. read )

Thirty years ago, South Africa’s first free elections brought Nelson Mandela to power. At this week’s polls, scandals and inefficiency could cost his ANC party its three-decades-old majority in Parliament.

( 4 min. read )

As the hush money case heads to the jury, it may be the least important criminal indictment against Donald Trump but likely the only one to come to trial before November.

( 5 min. read )

Despite an unprecedented array of Western sanctions, Russia has persevered, even prospered. Now the Kremlin appears to be consolidating its economy fully toward the waging of war in Ukraine.

In Pictures

( 2 min. read )

Helping owners care for their pets often requires trust and visibility in the community. This nonprofit is lending a paw to meet the challenge.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

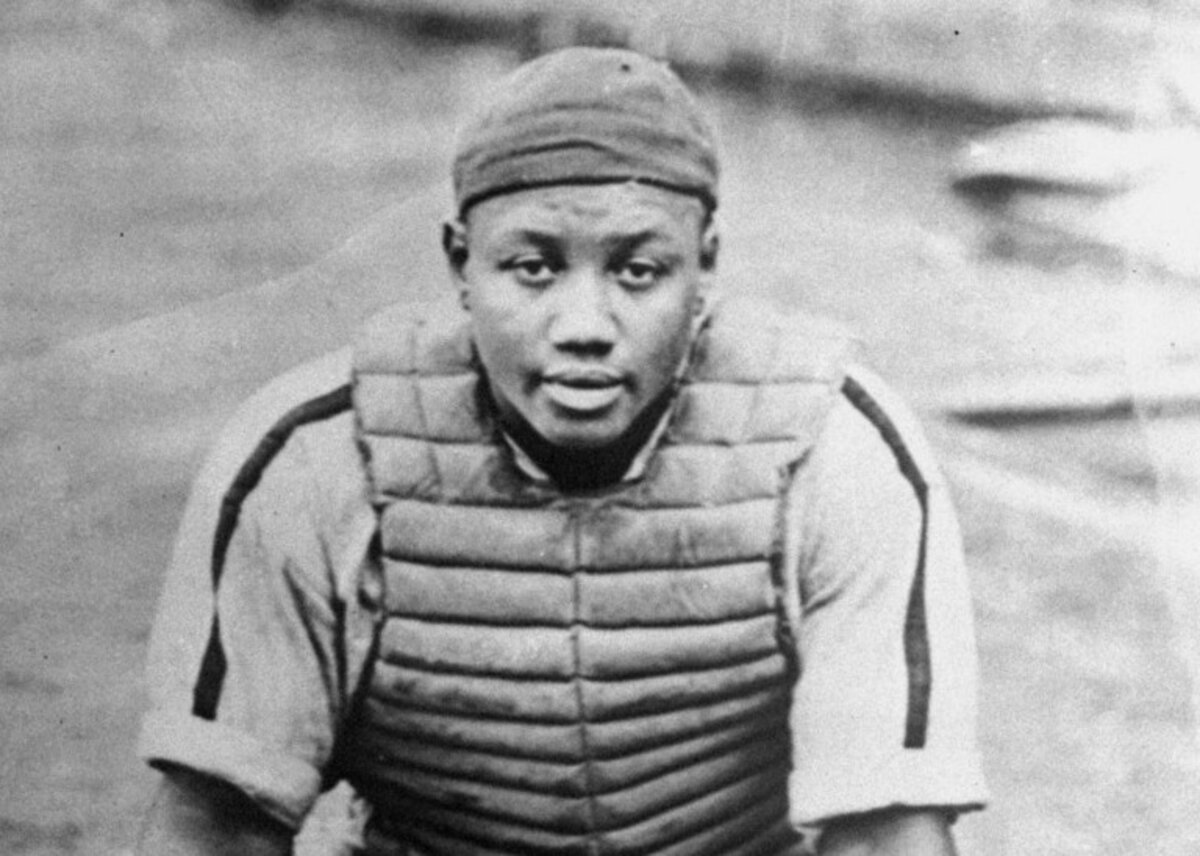

A great milestone in professional baseball was that day in April 1947 when Jackie Robinson strode onto Ebbets Field in Brooklyn as the first Black player in the major leagues. That began the end of the Negro Leagues, which had consisted of mainly Black players because of forced segregation. Now, baseball has a new milestone.

Pro ball has revised its record books, aggregating statistics on player performance from both leagues going back decades. In this new telling, for example, Black player Josh Gibson replaces Ty Cobb, Hugh Duffy, and Barry Bonds as the game’s greatest hitter. The new records result from painstaking historical and statistical work to fairly compare the performances of players in leagues without comparable seasons.

But baseball statistics aren’t just about what happened on the field. They capture a history of integration – from the first Jewish and Italian ballplayers to today’s Asian phenoms. Like curtains peeled back, batting averages and stolen bases are narratives of lived experience, lenses on how different communities experience America and what ultimately binds them.

What emerges is a deeper story of persistent dignity and the pursuit of equality expressed through excellence. Hank Aaron once criticized Willie Mays for not speaking out more against racism. Yet the “Say Hey Kid” made his case for inclusivity through hustle and home runs.

“People ... may be uncomfortable with some Negro League stars now on the leaderboards for career and seasons,” Larry Lester, a baseball historian who served on the committee that combined the record books, told The New York Times. What matters, he says, is the conversations they spark.

Baseball’s more inclusive narrative is part of a broader reckoning with how Black people have mitigated racial inequality. In her 2021 study of unpublished Black literature from the early 20th century, for example, New York University English Professor Elizabeth McHenry chronicles a history of resistance and resilience in the face of segregation and rejection. The 2016 film “Hidden Figures” portrayed the role of NASA’s Black female mathematicians in the space program.

One effect of these reshaped narratives is more empathy and humility. Following the death of George Floyd in 2020, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell said he wished “we had listened earlier” to professional football players kneeling during the national anthem to protest police violence.

A Stockholm University study on art and immigration noted last year how diverse societies are bound together by common points of reference. Harmony, or the “favourable conditions [of] a just, equal and inclusive society,” its author wrote, rests on a “collective consciousness” of shared values and rules.

Up until 1948, the ballplayers in the Negro Leagues confronted discrimination yet also dazzled fans and seeded Black journalism and entrepreneurship. But they were constantly told they were not good enough to face white ballplayers until Mr. Robinson broke the color barrier.

Now, the newly desegregated statistics of baseball’s segregated history “tell the story of the game, and the nation, inclusively,” as John Thorn, MLB’s official historian, told Rolling Stone. It is also a story of recognizing the innate talent of each individual, regardless of skin color.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 4 min. read )

Venturing to see life from the perspective of divine Love opens us to truly forgiving those who have hurt us.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we’ll look at what’s behind Ukraine’s largely unheralded success in opening up a secure Black Sea shipping corridor that has returned the country’s grain exports to near-prewar levels.