A felony conviction today does not preclude Donald Trump from running for or serving again as president. But it promises to scramble an already fraught campaign season.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

At morning meetings, Monitor editors jostle to get their writers’ work into the Daily. A heavy news flow has brought lots of friendly elbowing.

Besides the breaking news on the Donald Trump verdict, today’s lineup includes a must-read report from the Black Sea on how Ukraine might be quietly reopening a sea-lane, and an election-eve take from Mexico on what’s behind the (surprisingly limited) political noise around migrants.

Both reports – and the others – showcase our commitment to getting you the stories behind big stories.

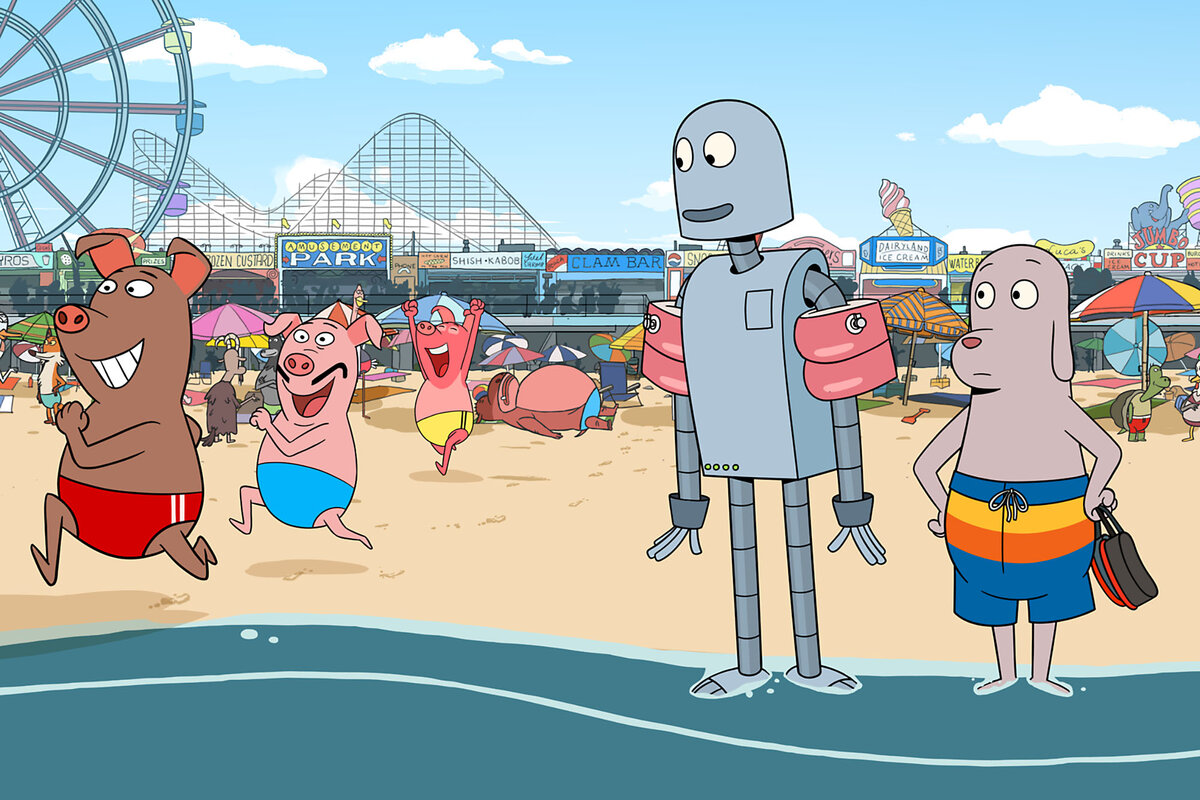

Finally, you can savor Peter Rainer’s film review. Of a director whose first animated movie, “Robot Dreams,” earns a rare five stars from Peter, he writes this: “He’s a voluptuary of the everyday.” Not bad for a Thursday.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Hong Kong verdicts: With the conviction of 14 pro-democracy activists, under a security law that may have them facing life in prison, Beijing all but wipes out public dissent following huge anti-government protests in 2019.

• France seeks to arm Ukraine: President Emmanuel Macron joins the head of NATO in pushing to allow Kyiv to strike military bases inside Russia with sophisticated long-range weapons provided by its Western partners.

• India faces heat wave: The temperature in Delhi reaches a record high of 52.9 degrees Celsius (127 F) on May 29 while parts of northwest and central India have been experiencing heat wave to severe heat wave conditions for weeks.

• Interest rates hover: Hopes for rate cuts this year by the U.S. Federal Reserve fade, with a stream of recent remarks by Fed officials underscoring their intention to keep borrowing costs high for as long as needed to curb inflation.

• Pandas return: Half a year after Washington, D.C., bid an emotional farewell to its giant pandas, the National Zoo announced that two more of the black-and-white icons will be returning by the end of the year.

( 6 min. read )

One lesson of the Russia-Ukraine war is that Ukrainian farmers’ prosperity and the world’s food security are very much linked. Now, in David-and-Goliath fashion, a Ukrainian sea drone has been deployed in the Black Sea to help keep the grain flowing.

Patterns

( 4 min. read )

Whether hard-right policies are enacted in Europe will depend largely on moderate conservatives fishing for votes in tempting far-right waters.

( 10 min. read )

The different ways in which immigration is influencing elections in the United States and in Mexico underscores each country’s distinct relationships with migrants and asylum-seekers.

( 4 min. read )

New curbs on press freedom have forced journalists in India to migrate from traditional outlets to YouTube. There, they find greater freedom to do their work, but little job security.

( 3 min. read )

When an animated film is invested with the full range of feeling, the result is “Robot Dreams.” The movie is a tribute to the beauty and frailty of friendship, our critic writes.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

In a globe-shifting moment this month, the world’s third-largest democracy officially began the process of joining a “club” of 38 nations that tracks one another’s dedication to good governance and inclusive growth. That was no small choice for Indonesia, a huge Southeast Asian country rife with corruption and trade protectionism but with hopes of becoming an advanced economy in two decades.

President Joko Widodo set up a team to launch reforms necessary for Indonesia to become a member of the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The OECD sets high standards for states in maintaining liberal democracy and free markets.

It also serves as a stamp of approval for foreign investors. With a large, young population, Indonesia needs faster economic growth and a high-tech industry to avoid the “trap” of remaining a middle-income nation. It now joins six other countries – Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Croatia, Peru, and Romania – wishing to join a body that sets global standards on individual liberty, rule of law, and the protection of human rights.

The OECD describes itself as “a like-minded community” committed to a rules-based international order. Its members represent 80% of global trade and investment. Indonesian officials like to cite reforms in two countries that recently joined the organization: Costa Rica has lowered its budget deficit as a percentage of its economy, while Colombia has reduced foreign bribery by following OECD rules on anti-corruption procedures.

One obstacle looms large for Indonesia, the world’s largest majority-Muslim country. It needs a sign-off from Israel, an OECD member, to join the group. While the two countries had cordial relations before the war in Gaza, Indonesia now strongly backs a Palestinian state. The incoming president, Prabowo Subianto, will need to persuade Indonesia’s powerful Muslim groups that the benefits of OECD membership outweigh its foreign policy on the Middle East.

Joining the OECD – and meeting its 200 policy standards – would help Indonesia hold itself to account for an already-strong democracy but one that needs deep economic reform, especially on corruption. Set up after World War II to help European democracies learn from each other, the OECD is little known but large in influence because of its data collection and policy expertise. Nations ready to make a leap in good governance know where to turn for guidance.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

Instead of just dipping our toes into the waters of prayer, we can immerse ourselves in communion with God, which brings tangible blessings.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for reading today. Come back tomorrow for a standout listen: Nearing retirement, veteran Monitor writer Peter Grier joins guest host Gail Chaddock on a special “Why We Wrote This” episode to discuss some of the stories – both writings and experiences – from his remarkable 45-year career.