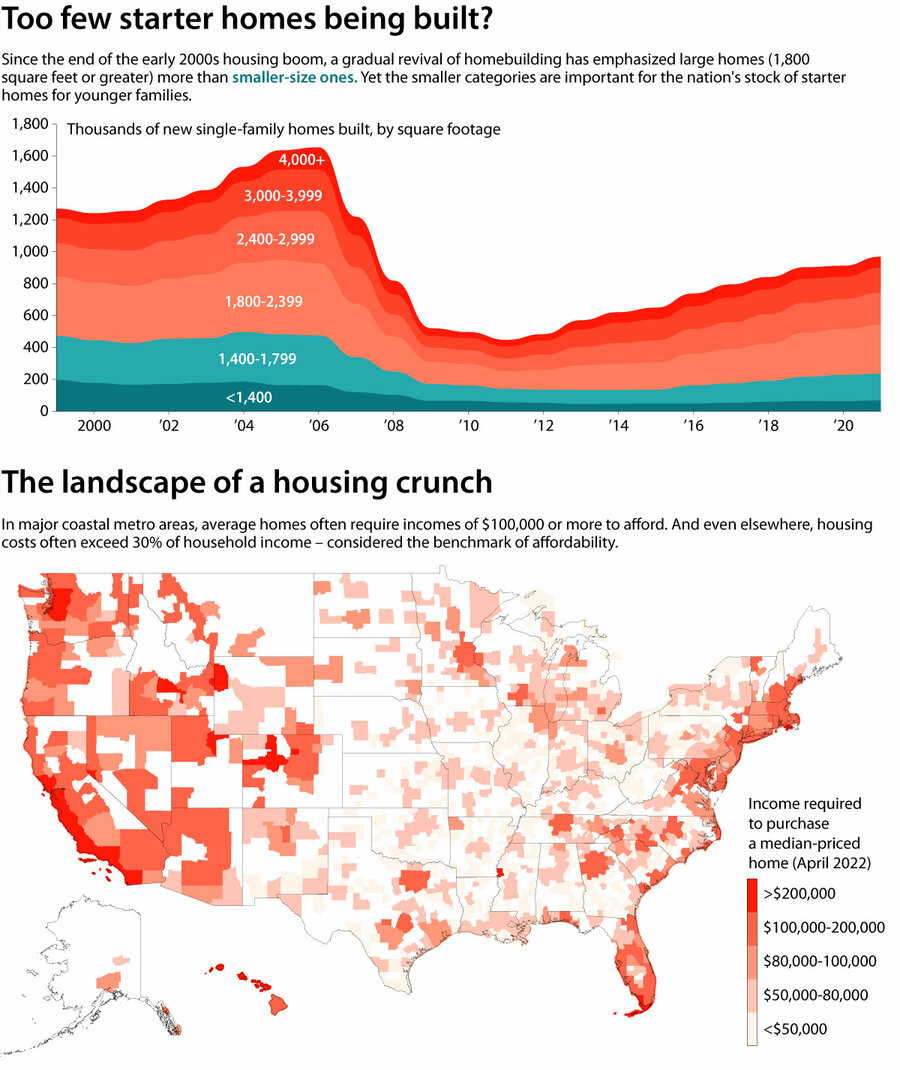

Concerns about a shortage of affordable housing were big even before mortgage interest rates spiked. Why so hard to fix? The challenges relate to market forces but also to choices about local land use.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Trudy Palmer

Trudy Palmer

I had a classic Monitor moment last night. Fred Weir’s story about parents and teachers in Russia pushing back against the government’s required patriotism lessons reminded me that you can’t judge citizens by their leader.

Schoolchildren were already top of mind for me because of a chipped, cracked serving bowl I reluctantly threw out over the weekend.

For well over a year, every time I used it, I wondered if that would be the moment the crack would worsen and the bowl would split. Finally, I decided to replace it.

Why was it so difficult to let it go? Because two little labels with my last name and an old phone number were still stuck to the bottom after countless washings. Seeing them always brought back memories of my daughter’s school days when I’d use the bowl to take a salad of some sort to a school potluck celebrating something or other. It didn’t really matter what.

The love in the classroom or playground or wherever we gathered was palpable. We loved our kids and were doing the best we could for them.

So are those Russian parents Fred wrote about, I realized. In trickier educational settings than I have ever faced, they are doing their best to pass along family values – instead of what many call propaganda – to their kids.

If they have school potlucks in Russia, I’m pretty sure I know what they feel like.