‘We first’ beats ‘me first.’ Ukraine war revives Western alliances.

Loading...

| London

Amicus certus in re incerta cernitur.

These wise words – best known these days through the English saying “a friend in need is a friend indeed” – were written by the Roman poet Quintus Ennius nearly 2,500 years before Vladimir Putin dramatically intensified Russian missile assaults on Ukraine this week.

But Ennius’ insight has taken on new relevance as America and Western Europe chart their response to the latest escalation in the war.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onNot long ago, Western alliances NATO and the EU were flagging and divided. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has given them new dynamism and sense of purpose.

So far, Mr. Putin’s invasion has had the effect of bringing old friends back together: reviving a divided and demoralized NATO, and giving the diverse nations of Western Europe a renewed sense of common purpose.

It has reminded leaders on both sides of the Atlantic of the value of alliances, especially in times of need. It has strikingly rebalanced the arguments in a vital geopolitical debate: me first, versus we first.

Yet that debate is far from definitively resolved. Centrifugal forces still threaten both NATO and the 27-nation European Union; their impact will determine the shape of world politics long after the war.

At issue is whether the joint commitment of democracies will contain the rise of autocracies, as U.S. President Joe Biden hopes, or whether Russian and Chinese “great power” claims to expanded influence prevail.

In the short term, NATO seems well positioned to sustain its rediscovered cohesion.

Founded after World War II to deter Soviet military expansion, the Western security alliance found itself searching for a new purpose after the USSR collapsed. Its member states began cutting their defense budgets and redirected the “peace dividend” toward spending priorities at home.

Mr. Putin’s invasion changed that mindset almost overnight. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced a multibillion-dollar fund to increase defense spending. Virtually all NATO’s European member states moved to help provide weapons and other support for Ukraine.

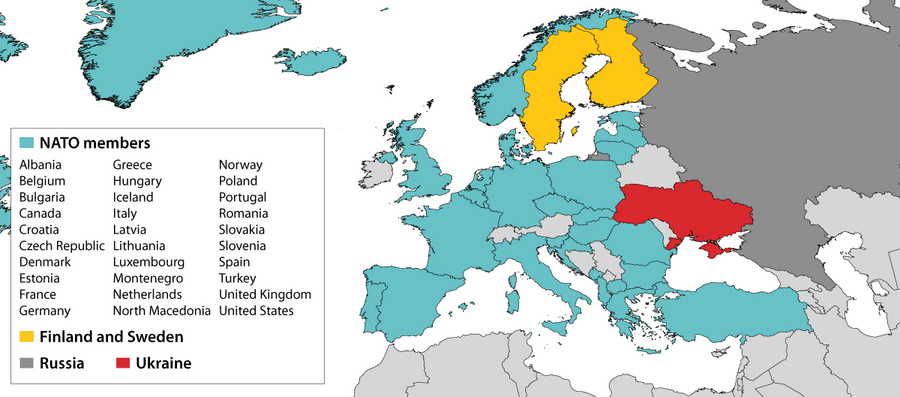

Most dramatically, Finland and Sweden – democracies on Russia’s western flank long wedded to neutrality as the best formula for coexisting with Moscow – have opted to join NATO.

Still, the war has also revealed potential signs of future strain. And the move by the two Nordic countries underlines one of them: NATO’s European fulcrum has shifted eastward.

The countries nearest to Russia are the ones that have responded most robustly to the invasion – Poland, the Czech Republic, and the Baltic states, which have experienced Moscow’s domination in the past. But while Germany has begun to increase defense spending, both Berlin and Paris have been far less ready to provide military support for Ukraine than other NATO partners.

The greatest test of NATO’s new cohesion in the long run, though, may lie with its richest and most powerful member, the United States.

Washington has played a key role in forging NATO’s Ukraine policy, and has provided the lion’s share of military equipment to Kyiv. And Mr. Biden has done so with a measure of bipartisan support not seen for years.

But especially if the Republican Party regains control of Congress in next month’s midterm elections, that across-the-aisle mood could begin to wane, at least among pro-Donald Trump legislators.

As president, Mr. Trump dismissed NATO as a protection racket in which European members freeloaded off America. He told security aides that Washington should get out of NATO altogether.

European states will also be watching the midterms. During the Trump years, a number of them became convinced of the need to plan for their security future without Washington as a key partner.

Just as Putin’s war has galvanized NATO, it has also brought the EU closer together.

Though founded as a trading and economic bloc, the EU has earmarked large sums to fund military equipment for Ukraine. It has framed the war as an existential contest between an autocrat’s aggression and the “European values” of democracy.

But within the EU, too, the war has revealed potential tensions, especially since energy shortages seem likely to hit hard this winter.

The initial response to that challenge was broadly unified: a move to slash the imports of Russian gas on which a number of member states had come to rely, and, more recently, agreement on a phased end to imports of Russian oil.

But Germany has since decided to go it alone, crafting a $200 billion package to cushion the impact of winter energy costs on industry and domestic consumers. That plan has been criticized by other EU member states for undermining the bloc’s “single market” foundations.

Their hope, echoed by the bloc’s chief executive, Ursula von der Leyen, is for a united response, in which the EU would use its collective muscle to buy energy on the world market and then distribute it among member states.

The bloc’s immediate challenge, as for NATO, is to maintain its unity of purpose in response to the war.

Russia’s latest missile strikes seem likely to reinforce, not dent, Western resolve. Germany has already responded by sending Ukraine the first of a number of long-delayed air-defense systems.

But securing the longer-term cohesion of NATO and the EU could prove a stiffer test. If they are to meet that challenge, they will need to do more than keep the words of an ancient Roman poet in mind, once the immediate “need” for friends recedes.

Perhaps they should, instead, heed an old Irish proverb: “A good friend is like a four-leaf clover: hard to find and lucky to have.”