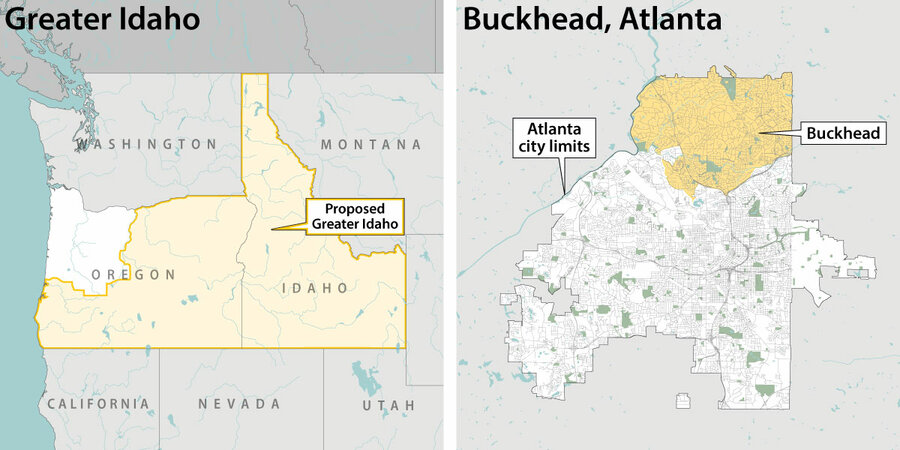

Values and identity are key to many of the movements motivated by America’s growing urban-rural divide. As cities have expanded, some in rural areas are feeling left behind – and looking to “move” without giving up their homes.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Laurent Belsie

Laurent Belsie

I coped with the toilet paper shortage, learned patience with the week-after-week no-show of Lysol disinfectant wipes, and put off buying a new laptop because of the global chip shortage.

But Chinese food? Really?

For the second time in three weeks, I’ve had to search high and low for hoisin sauce and water chestnuts – key ingredients for a favorite meal for our adopted Chinese daughters. My two go-to grocery stores had given up trying for that full-but-shallow look where the shelves are neatly stacked with goods exactly one bottle or can deep. Instead, almost-bare shelves have been strewn with a mishmash of Asian food products in no particular order, like a toddler’s bedroom floor after playtime.

Maybe it was just hoarders anxious they wouldn’t have enough for yesterday’s Lunar New Year celebrations. But for me, it’s a personal metaphor for the supply-chain fix we’re in. Yes, manufacturers and retailers have risen to the occasion to keep stores mostly filled. But the pandemic has stretched the infrastructure that connects them. Nearly two years into the pandemic, a labor shortage – based in part on fear of going back to work – means a backlog of container ships in U.S. ports, too few truck drivers to get the goods to stores, and a lack of retail employees to stock the shelves with those goods.

This was the year supply chains were supposed to get back to normal. But I’m not seeing it yet. Typically, a grocery store will be out of stock on 5% to 10% of its items, according to the Consumer Brands Association. As of Sunday, unavailability was averaging 15%. Now comes news that China’s COVID-related lockdowns, already causing food shortages for some Chinese, may trigger more supply-chain woes worldwide.

A happy Chinese New Year? I hope so.