With Russian hackers in mind, NATO takes hard look at cyber strategy

Loading...

| Brussels

Article 5 is the linchpin of the NATO pact, putting adversaries on notice that an attack against one is an attack against all. Founded on the Cold War logic of deterrence, the idea is that no aggressor will strike for fear of certain retaliation from combined NATO forces.

But with modern warfare expanding to virtual battlefields, NATO strategists are overhauling their cyber tactics. That means rethinking the concept of deterrence, as well as what constitutes a cyberattack that triggers Article 5: a crucial issue amid tensions between Russia and NATO-supported (though nonmember) Ukraine.

Since 2019 it has been clear that a large-scale cyberattack on a member could trigger Article 5. But last year, the alliance quietly announced that a series of lower-level cyberattacks could, cumulatively, be a tripwire for the article as well. The move marked a sea change in NATO cyber strategy, and sparked questions about how best to bolster NATO cyber defenses – and if offense, of a sort, might be part of the solution, too.

Why We Wrote This

NATO has based its security policy on deterrence, via a mutual defense pact among members. But its strategists are rethinking that approach when it comes to the digital battlefield.

“It’s a total change in how NATO views Article 5, and it actually could be perceived as escalatory and spiral out of control,” says Stefan Soesanto, senior researcher in the Cyberdefense Project with the Risk and Resilience Team at the Center for Security Studies in Zurich. “No one is really sure whether and when Article 5 will apply.”

NATO officials acknowledge that the opaqueness is part of the point. “Up until now, the idea [among cyber adversaries] was, if we don’t completely disable a full country’s infrastructure, it’ll probably be OK. With the new policy we’re saying, well, that’s not necessarily true,” David van Weel, NATO’s assistant secretary-general for emerging security challenges, said at a discussion with journalists in Brussels in December. “I’m making it less defined. Sorry for that.”

Are enemies deterred?

For the alliance, this ambiguity was a “sorry, not sorry” moment.

That’s because among NATO’s security planners, there has been a growing belief that the military strategy of deterrence – so apt during the Cold War nuclear era – simply hasn’t worked in cyberspace.

“I would feel pretty confident in telling you that there is probably a scale of cyberattack that is deterred: absolute destruction. Clearly attacks like that don’t happen every day. But the scale of cyberespionage and the scale of cyberattacks is growing, and the frequency is very high,” said David Cattler, NATO’s assistant secretary-general for joint intelligence and security, at the December discussion in Brussels. “I’d say on balance, except for probably some really big efforts, [adversaries] are not deterred.”

Reassessing the relevance of deterrence in cyberspace marks a major shift in military strategic thinking, says Richard Harknett, U.S. Cyber Command’s 2016 scholar-in-residence.

A holdover from the Cold War, the idea behind deterrence and escalation, too, is that since there’s no defending against a nuclear attack, the key is convincing an opponent that launching one is too costly in the first place. Until recently, there’s been a belief in cyber that “we’re not threatening enough. We don’t have the punishment right,” Mr. Harknett says. Strategy as it’s currently being pioneered is less about trying to arrest all hacking operations – an unrealistic prospect given the interconnectedness of the internet – as it is to understand and shape them so allies can better protect themselves.

After historically taking “a very defensive approach” to cyber operations, officials are now mulling whether there is “anything from an offensive perspective that this alliance wants to have in its tool kit,” Ambassador Julianne Smith, U.S. permanent representative to NATO, said at a discussion sponsored by the German Marshall Fund of the United States last month in Brussels.

The limits of Article 5

In crafting NATO’s new cyber strategy, senior security and intelligence officials for the alliance say they were informed by a series of “increasingly destructive” cyberattacks by Russian and Chinese actors over the last few years.

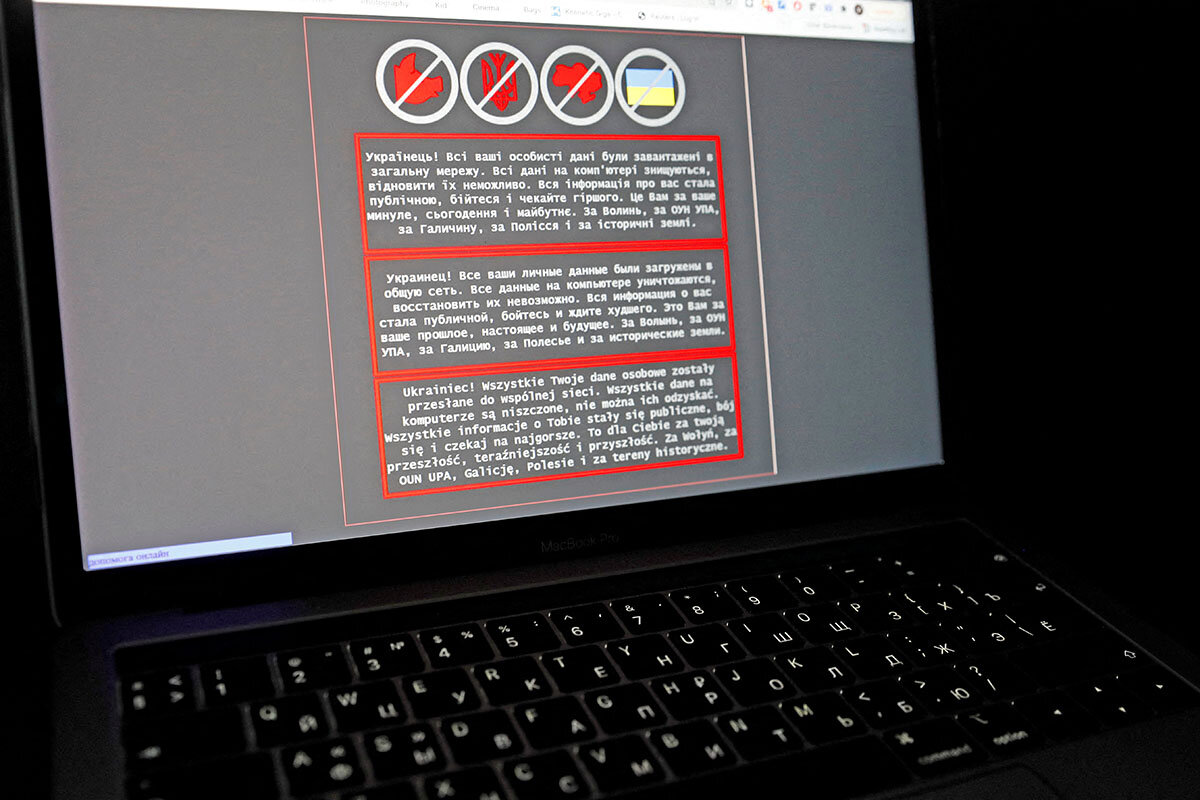

When Ukraine was hit by a spate of strikes on its government computer systems in January, as Russian troops massed on its border, NATO officials were watching closely. They had been working “for years,” they noted, to shore up the embattled nation’s cyber defenses, though it’s not a NATO member entitled to Article 5 protections.

What the incursions had in common was that, though damaging, they fell below the threshold of armed attack. It was increasingly evident, too, that the alliance needed to be more “proactive” in cyberspace, Mr. van Weel said. “It’s about not limiting our options to just waiting for a massive attack. It’s about recognizing that what happens below that threshold of a massive attack is worthy of our attention.”

But NATO doesn’t want to be too clear about what the new threshold is, Mr. van Weel added. “The key to the policy is that there is no set bar, and there is a deterrent effect that will go from that.”

Behind the scenes, as cyberattacks were playing out, the U.S. was doing some heavy lobbying for a shift in the alliance’s strategic thinking, says Max Smeets, director of the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative. This was driven in large part by the Russian meddling in Western elections, and the dawning understanding that a series of cyberattacks can cumulatively tear away at the fabric of democratic society.

In response, U.S. Central Command quietly began deploying proactive expert U.S. military hackers, known as “hunt forward” teams, to operate “outside the United States against our adversaries, before they could do harm to us,” as the group’s head, Gen. Paul Nakasone, explained at the Reagan National Defense Forum in December.

“Hunting forward”

Some military analysts believe that a greater motivation behind NATO’s Article 5 policy shift is to set legal groundwork for allies to work together proactively in a way that is difficult without invoking collective defense mandates under Article 5 – particularly given some NATO members’ reticence about intelligence-sharing.

A potential model for such operations was on display in 2018, when U.S. Cyber Command launched its first known cyber response to Russia for election meddling. In the run-up to the 2018 midterm vote, U.S. military cyber operators “popped up” on the screens of workers at the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Russian state-sponsored troll farm that carried out damaging online influence operations during the U.S. election.

“They just showed up on the system and said hello,” says Mr. Harknett, now a professor of political science at the University of Cincinnati and co-author of the forthcoming, “Cyber Persistence Theory: Redefining National Security in Cyber Space.” They also blocked the IRA’s internet access, a move calculated to put the Russians on the defensive and sow confusion. “They had to be thinking, ‘Americans couldn’t have done all this work just to show up on our screens and say hi. How did they get in?’”

The response among NATO adversaries to such operations remains to be seen, says Mr. Soesanto. “By the Russians, on Russian soil, it could definitely be perceived as escalatory.” At the same time, what U.S. Cyber Command did “was temporarily shut down IRA, but it didn’t stop them.”

Yet the impact of these operations may be less obvious, Mr. Harknett says. “‘Hunting forward’ means you actually have to be in the networks of your adversaries to understand malware development and the vulnerabilities they seek to exploit,” he notes. “A lot of criticism has been made that this is being aggressive, going on the offensive, that it could escalate.” But often, “they don’t even know we were in there.”

Deliberations about the efficacy, politics, and ethics of offensive cyberweapons are likely to be more challenging for the alliance than 20th-century discussions “about tanks rolling across the border, in which case we know how to respond and what to do,” said Ambassador Smith. “And there are still tough conversations to be had.”