The very public nature of the fight between the US president and the former head of the FBI could complicate their dispute from a legal standpoint. As this piece points out, it also masks a deeper dispute: about how much authority the Constitution grants presidents around overseeing law enforcement and prosecutions.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Clayton Collins

Clayton Collins

Few years in modern history cast as long a shadow as does 1968.

The United States endured assassinations and a political convention turned violent. The antiwar and civil rights movements clenched their fists. Europe saw the Prague Spring and French rioting.

Over the weekend Britain revisited a major political speech given that year – 50 years ago this week – by Enoch Powell, a Conservative member of Parliament. It heaped scorn on racial integration. It went much further. Called the “rivers of blood” speech, it rippled fast and far, stirring fear of immigrants, raising the specter of the British-born seeing “their homes and neighborhoods changed beyond recognition.”

Voiced by a British actor, it was broadcast Saturday by the BBC show Archive on 4. The stated aim: journalistic analysis and a chance to examine and educate about an important moment in British political history. But as it approached, it stirred deep debate.

Some were outraged. Why deepen the divisiveness – the anger at “the other” that’s on stark display in Europe and the US today? Some advanced another view: that the dissection of hateful oratory can help spread the sort of cleansing light that’s inspiring such acts of resistance as the massive pushback rallies in Hungary.

That kind of tense introspection also followed a New York Times piece about a modern-day Nazi sympathizer in Ohio last year. It has attended conversations in Germany over whether to bury parts of its past.

One modern take on Powell comes from BBC media editor Amol Rajan. Born to immigrant parents and raised in South London, he was a panelist on Saturday’s broadcast. “It’s impossible not to feel that the intemperance of [Powell’s] language,” he said, “set back the very cause that he was espousing.”

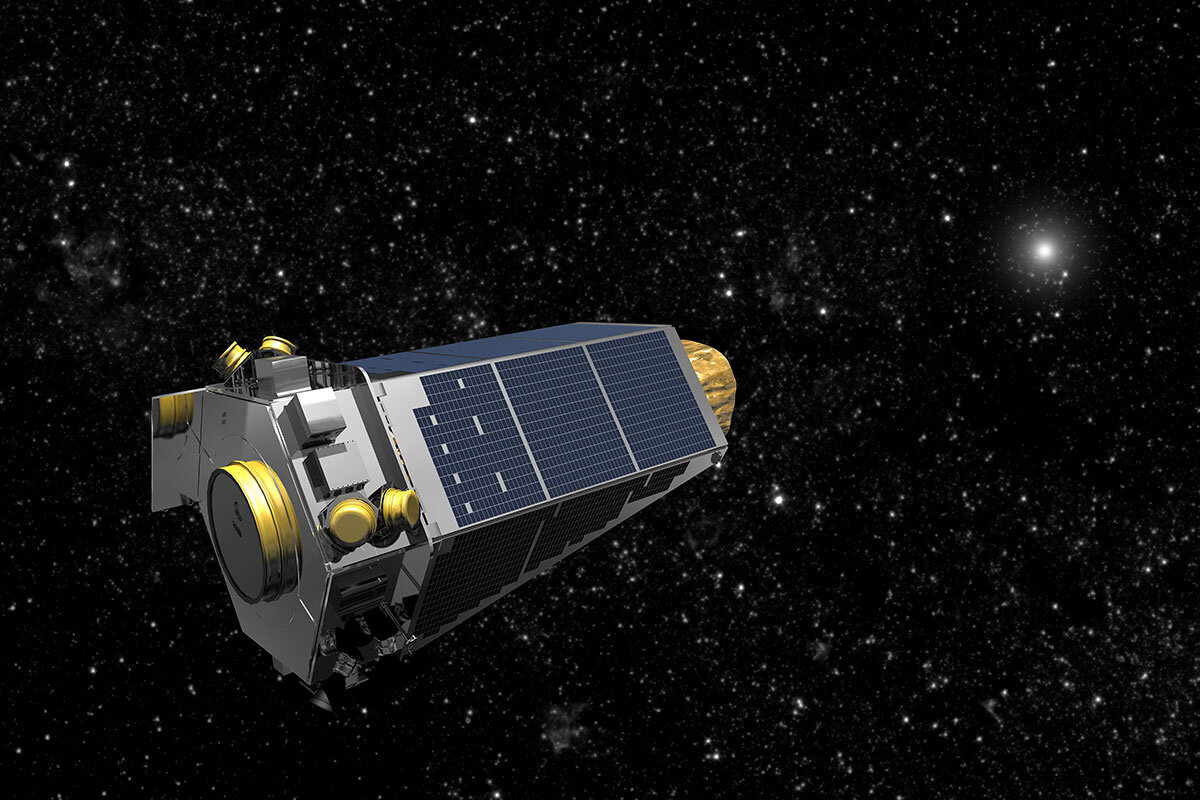

Now to our five stories for your Monday, highlighting guardrails in politics and war; youth-driven change in Kansas and India; and a celebration of galactic discovery.