In a land ‘shaped by water,’ a family tale of persistence

Loading...

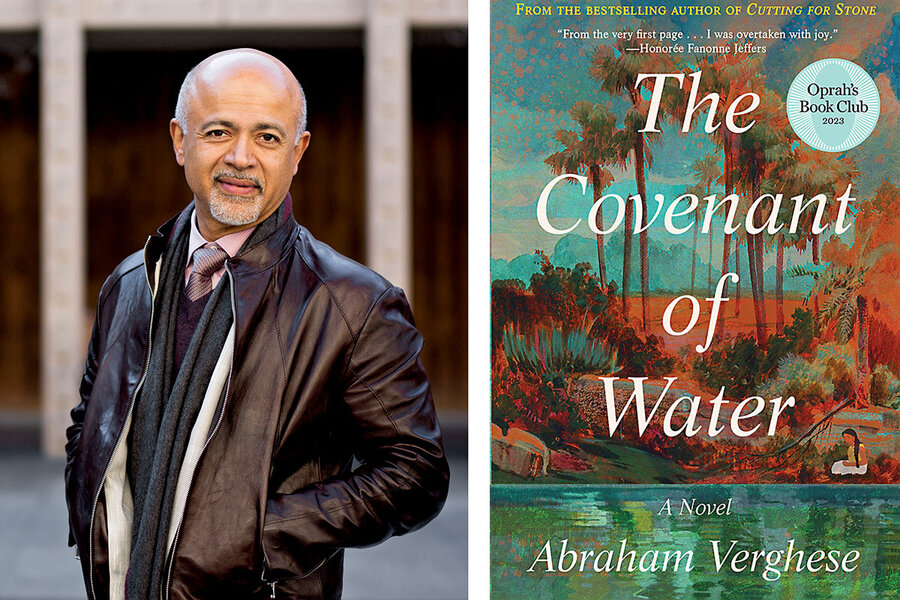

“The Covenant of Water,” the latest novel from bestselling author Abraham Verghese, delivers a magnificent saga. Bursting with myriad characters, well-braided plotlines, politics, history, faith, and geography, the story centers on a young Christian girl in water-rich Kerala, India, who is married into the landowning Parambil clan. Unknown to her, the Parambil men appear to suffer from a curse – death by drowning. As the girl matures and builds a family with her much older husband, the many challenges of life in 1900s colonial India buffet the household. It’s an engrossing tale of persistence that offers much to ponder about creativity and the connectedness of life. Contributing writer Erin Douglass interviewed Mr. Verghese, who was born in India, grew up in Ethiopia, and studied medicine in multiple countries before completing his residency in the United States. He teaches at Stanford University and lives and practices in Palo Alto, California.

You describe the book’s primary setting in south India as a land shaped by water. And yet, we have the Parambil family, whose men seem to be cursed by a history of drownings. Why create a series of characters so at odds with their environment?

It’s an automatic method of generating conflict. ... You have a land where water is the giant circulatory system that connects everybody and the monsoon is the beating heart, so people learn to swim before they learn to walk. And then you have a family where individuals can’t do that. To me, that was an interesting challenge.

A standout character – a 40-year-old widower engaged to a 12-year-old bride – is revealed to be a principled, kind man. What about him surprised you while writing the book – or was he fully formed in your mind?

I don’t think any of the characters came fully formed. And I do think it was a bit risky to begin with a 12-year-old bride. In choosing a widower, I was actually embarking on the story of my great-grandmother, which was very similar. I don’t know many of the details about who he was or who she was – I didn’t know them – but she married a widower with some kids. ... He obviously died before her because he was considerably older, but, by all accounts, it was just the most beautiful, happy marriage.

You introduce “pariah” figures in the novel. What do you hope readers take away from these characters and their experiences of caste, prejudice, and racial hierarchy?

My aims are always the same, which is a good story well told. Having made the decision of locating the story in the south of India and during this time period of 1900-1977, you really can’t escape issues of caste.

Drawing – and later sculpting and creating other art – is a healing act in the novel. What interests you about creativity?

This novel had a lot of impetus from a document that my mother left behind, trying to write out for her 5-year-old granddaughter what her world was like at 5. My mother was born in the 1920s and got her physics degree in India, just about the time of Indian independence, and there were no jobs. So, in a sari, answering an ad, she went sailing to Ethiopia as a single woman. It’s quite incredible to imagine. In her notebook, describing all these anecdotes of her childhood, she was also sketching. She was a very good artist herself. So perhaps that’s what really gave me the license for one of the characters to be an artist.

You write about a character experiencing a church service and feeling “part of the fabric instead of a thread torn from the whole.” What is the place of religious ritual?

Rituals are terribly important. From an anthropological point of view, we’ve come to understand that rituals – weddings and funerals and church services – they’re all always about transformation. I think that they’re terribly important to our psyches.

I began this book, in part, because I was fascinated with the rituals of my community [of St. Thomas Christians]. Rituals that were a bit foreign to me in the sense that I grew up in Africa [as opposed to India], but at the same time very familiar. I was in awe of these rituals that were so deeply embedded. And they were also a mix of Hinduism with Christianity. Since [adherents] were converted by St. Thomas from Hinduism, little symbolic things, like the necklace that the bride wears, is a cross but it’s on a gold tulsi leaf, which is exactly what the Hindus do. ... I love the sense that even though this was a different religion, it had all these elements from the other faith brought in.

You write, “Things have a way of coming back when we think they’re gone forever.” Would you say that’s an important theme?

Yeah, I guess I would agree if that’s what someone sees in the book!

My understanding of how this works is that the writer provides the words, the reader provides their imagination, and in that middle space, [readers] create this fictional movie. It’s theirs to own, and it’s very different from the next person who reads the book. So if the reader sees themes and preplanned paths that I’m supposed to have taken, I don’t dispute them, because I’ve found strange things happen.