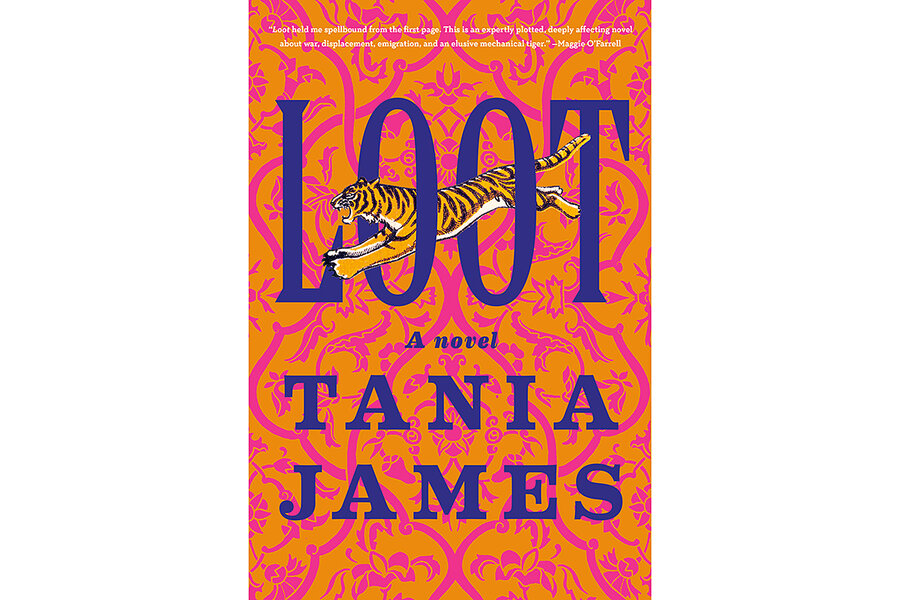

‘Loot’ weaves an epic tale of imperialism, plunder, and autonomy

Loading...

In late 18th-century India, a large automaton depicting a near life-size wooden tiger mauling an Englishman was created for Tipu Sultan, the Muslim ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore. Internal mechanisms and a pipe organ stowed within the two figures’ cavities caused the tiger to emit grunts, the man to wail, and various parts of the structure to move. Since 1880, the curiosity has been a popular attraction in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, among other spoils of war seized from the imperial courts of south India.

“Loot,” Tania James’ dazzling, richly embroidered historical novel, imagines the circumstances behind the fabrication of this ingenious toy, which gruesomely expressed Tipu’s hatred for the English and the East India Company’s armies that threatened his sovereignty.

James has structured her third novel around the profound effect the automaton has on the people who connect with it throughout its decadeslong journey from a sultan’s whim to a prized plunder. In doing so, she has found a clever angle from which to explore the dark legacy of colonialism and the quest for betterment, autonomy, and love among those displaced by it.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn this rich epic saga, the journey of a mechanical tiger symbolizes the painful legacy of colonialism and the pursuit of self-determination.

The novel begins in Srirangapatna, Mysore, in 1794, when Abbas, a gifted 17-year-old woodworker, is summoned to Tipu’s Summer Palace to work under the tutelage of a French master inventor and watchmaker named Lucien Du Leze. They are given just six weeks to create a novelty meant to enchant Tipu’s young sons, recently returned from English custody in Madras, where they were held as collateral until Tipu met the punishing financial terms of a peace treaty following a humiliating defeat at Bangalore.

Neither artisan has a choice in the matter: Du Leze, sent over from France by Louis XVI, has been trapped unhappily in India due to the French Revolution. In Mysore, where spies are said to “outnumber the people,” everyone knows they must submit to power. In case there’s any doubt, Tipu alludes to the terrible fate of a friend of Abbas’ who apparently betrayed the regime. The sultan reminds the boy that his life, too, is in jeopardy: “Really anything is punishable by death if I say so.”

James’ mastery of the tools and vocabulary of woodworking is impressive, but it is her meticulous development of the respectful relationship between teacher and apprentice that lifts her story to another level. Ambitious Abbas, thrilled to have “risen past his station” with his role in the automaton’s creation, recognizes that his despairing, homesick teacher is “a ticket to greater things.” But he also knows that his future is anything but certain.

“Loot” is masterfully plotted, moving quickly from Tipu’s desperate last months to the British conquest of Srirangapatna and beyond. Abbas later observes, “Goats are slaughtered with greater care.”

James keeps things lively with plenty of action and welcome flashes of wit. Traveling between continents, her characters sail on trade ships vexed by disease and pirates. In an English castle, Lady Selwyn, an eccentric, rich widow with a passion for South Asian art carries on a clandestine affair with her personal secretary, a Brahmin who served as aide de camp in Mysore to her late husband.

Tipu’s library and what becomes known as the Tipu Tiger have easier passage from India to England than the human cargo. In a wonderful move, James briefly turns over her narrative to the fictional journal of a British seaman named Thomas Beddicker to provide a vivid view of her hero’s exodus from his devastated homeland. Beddicker relays conversations with Abbas during their shared night watches. At one point, Beddicker confesses his dream to captain his own ship and hire Abbas as head carpenter. But Abbas demurs: “You must understand, I did not come through such misery in order to serve others. Now I serve myself.” Abbas’ dream is to create something “that would outlast him, and for which he would be remembered.”

Abbas, determined to make his talent visible to “the unkind world,” yearns to “move through the world with a natural ease.” But in France and England, where race and class trump talent, he learns “how much harder it is to cultivate ease in a world that is wary of you.” While James doesn’t explicitly draw the connection, there are discomfiting similarities between her émigrés – trapped in subservience without dominion over their futures – and the foxes hunted on Lady Selwyn’s country estate.

People meet, lose, and reconnect with each other in unexpected ways throughout “Loot.” Perpetually on their guard, they are sometimes slow to trust and recognize love. Among other narrative drivers, “Loot” features a “will-they-or-won’t-they” subplot.

James has pulled off something special in this ingeniously constructed novel. By creating characters who steadfastly refuse to become plunder themselves, she has produced an inspiring work of beauty sure to leave its mark on readers.