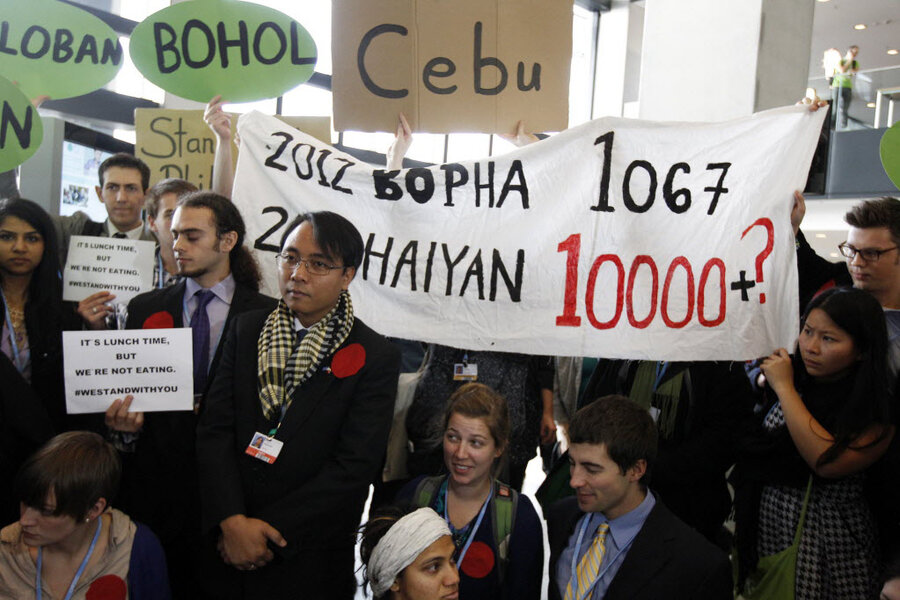

Is global warming generating storms like Typhoon Haiyan?

Loading...

Financial losses from tropical cyclones and other severe weather have surged in the past few decades, even as the man-caused release of carbon into the atmosphere has similarly increased and the science for why we're living on a warming planet has been nailed down.

So global warming is causing stronger, more frequent storms right? Wrong. At least, as far as anyone can make out, there's no evidence of that yet.

Historical Global Tropical Cyclone Landfalls, an article in the July 2012 Journal of Climate, argues that no evidence yet exists that climate change is to blame for more dangerous tropical cyclones – the generic name for hurricanes and typhoons. The authors constructed a database of hurricane-strength landfalls of tropical cyclones over the years, but found that "The analysis does not indicate significant long-period global or individual basin trends in the frequency or intensity of landfalling (tropical cyclones) of minor or major hurricane strength."

In other words, no consistent pattern, and no evidence that storms are growing stronger or more destructive globally. Why more damage? Because more people are living in flood plains and near the coast and building more things there. Also, there's a lot more of us around today: In 1960, the planet held 3 billion people. Today, it's more than 7 billion.

This is not to say that a warmer climate won't lead to more powerful and damaging tropical cyclones. Warm surface ocean temperatures are linked to stronger cyclones. But it's just that it doesn't appear to have done so yet. While the conventional wisdom on this often feels driven by people seeking to use to the latest storm headline to push back on global-warming denialists, the ends still don't justify the misuse-of-information means.

It's a popular position that tropical cyclones are more damaging now. For instance Jeffrey Sachs, the economist and director of Columbia University's Earth Institute, wrote this morning:

"Increasing Intensity of the Strongest Tropical Cyclones," published 2008, demonstrated that disasters like Haiyan becoming more common.

— Jeffrey D. Sachs (@JeffDSachs) November 12, 2013

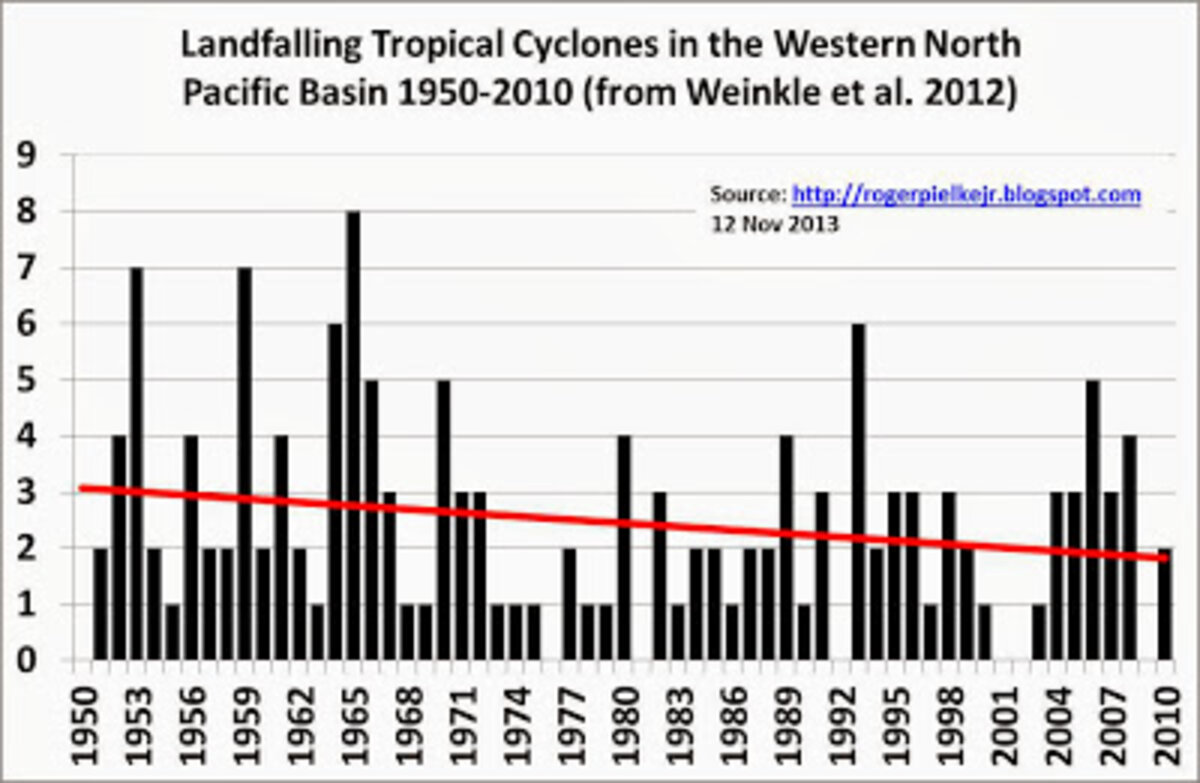

That prompted a response from Roger Pielke, one of the authors of the paper referenced at the top of this post. In a blog post on the matter, he acknowledges the paper referenced by Dr. Sachs found some change in some places, but not the sort of evidence of a global trend claimed. He also teases out regional data from the Landfalls paper for the western North Pacific basin, where Haiyan formed and which he writes is the most active for tropical cyclone formation.

If anything, the trend since 1950 has been towards fewer strong tropical cyclones in the area (though he warns that doesn't mean much either since there's such high year-to-year variability).

The paper Dr. Pielke contributed to (the lead author was Jessica Weinkle of the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research at the University of Colorado) isn't exactly an outlier. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) surveyed the scientific literature on stronger or more frequent cyclones in a working paper in September of this year. It found:

Current datasets indicate no significant observed trends in global tropical cyclone frequency over the past century and it remains uncertain whether any reported long-term increases in tropical cyclone frequency are robust, after accounting for past changes in observing capabilities (Knutson et al., 2010). Regional trends in tropical cyclone frequency and the frequency of very intense tropical cyclones have been identified in the North Atlantic and these appear robust since the 1970s (Kossin et al. 2007) (very high confidence). However, argument reigns over the cause of the increase and on longer time scales the fidelity of these trends is debated (Landsea et al., 2006; Holland and Webster, 2007; Landsea, 2007; Mann et al., 2007b)... No robust trends in annual numbers of tropical storms, hurricanes and major hurricanes counts have been identified over the past 100 years in the North Atlantic basin.

None of this should suggest a warmer climate isn't a threat – or won't very clearly threaten more lives and livelihoods when powerful storms strike land. Rising sea-levels will make more and more places inhabited by people flood prone – which means more devastating storm surges. And human beings continue to love to live along the coast – whether for livelihood reasons for the poorer among us, or for the views and lifestyle among the rich.

But Haiyan isn't provably a result of a warmer planet. Nor is there yet strong evidence that global storms are more destructive.