Why Spain's militant ETA may be ending with a whimper

Loading...

| Bilbao, Spain

Jose Antonio Fernandez joined ETA, the armed Basque separatist group, in his early twenties, at a time when Spain was still reeling from the fall of its dictatorship. Those were ETA's bloodiest years, when political assassinations and bombings shook a fragile democracy and claimed the lives of over 800 people.

Now ETA is fading into irrelevance, its tactics discredited and its strength sapped by relentless police operations. And Mr. Fernandez, a calm, soft-spoken man in his mid-fifties who spent 22 years in jail for his role in ETA killings, is speaking about his violent past. He picks his words carefully, mindful of Spanish anti-terror laws that could land him back in detention. Does he regret what he did?

“No,” Fernandez says, with little emotion. “For me it was necessary, correct and fair.”

As its local support base crumbles, ETA faces increasing pressure to disarm and disband. In 2011, it unilaterally declared a “permanent” ceasefire. Last Friday, the group invited a team of international mediators to witness a partial disarmament of its stockpile of arms and explosives.

This has been controversial: Spanish Police Director Ignacio Cosido told the EFE news agency that “the real verifiers” of ETA's disarmament will be Spain’s security forces. Madrid has repeatedly played down the role of outside mediators and says it won’t negotiate with a “terrorist group.”

Some analysts believe ETA is dragging its feet on decommissioning to leave itself with some bargaining chips. ETA declared a previous ceasefire in 2006, but later carried out a bomb attack at Madrid’s international airport.

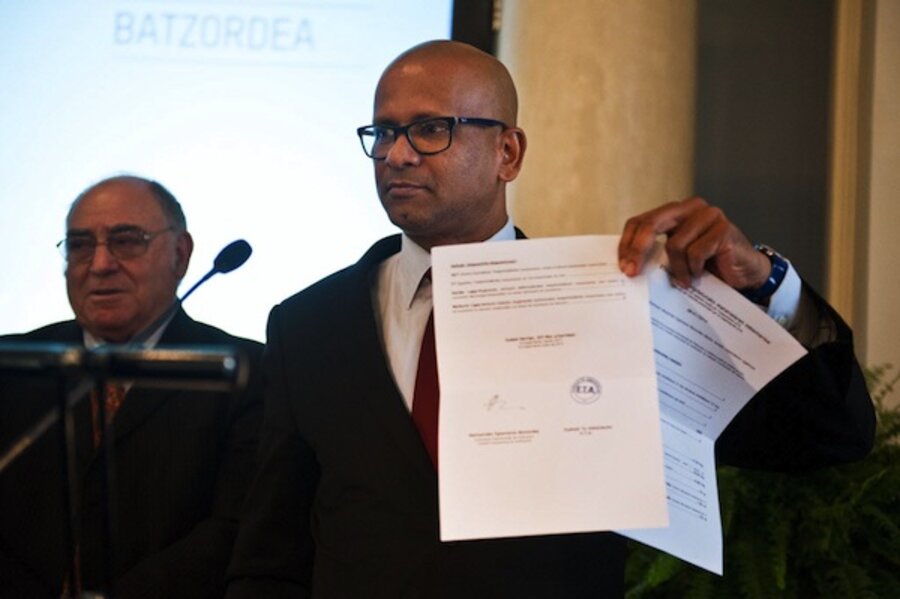

The group has stood by its 2011 agreement, said Ram Manikkalingam, the director of a network of mediators who have worked in conflict zones like Northern Ireland and Sri Lanka and are overseeing the ETA's disarmament. The mediators were shown a cache of weapons that were rendered inoperable recently that he said included 36 pounds of explosives, one assault rifle, two anti-tank grenades, three pistols, and 300 rounds of ammunition.

Still, many saw the gesture as insignificant.

“It was quite small, a rather token effort considering what the group likely has,” said James Bevan, a British weapons specialist and consultant to the European Union and the United Nations. “If I were to do a haul around my North London neighborhood, I would probably pull in more.”

Armed struggle

It’s all a long way from Fernandez’s childhood in Bilbao. Dictator Francisco Franco had been in power since 1936 and had banned the teaching of Euskera, the Basque language that is today spoken by about one million people; regional cultures in Spain were also suppressed in the name of national identity. Fernandez remembers the ever-present military police on the streets and the fear of arbitrary detention. [Editors note: the current number of Basque speakers was originally misstated.]

In this climate, Fernandez was drawn to armed struggle in the name of Basque independence. Via friends, he was brought into the organization in 1978 and put to work as a “legal commando” in a cell called Poeta – living openly, holding down a job in a furniture factory, and raising a family. ETA killed 66 people that year.

Burly and stoic, Fernandez's friends called him Magilla, because of his resemblance to the American cartoon gorilla. As a member of ETA, his name was Iru.

“You go about your normal life, you work a normal job, and later after work instead of going to watch soccer, you carried out actions,” he explains, declining to provide specifics.

These actions eventually landed Fernandez behind bars: He and other members of his unit were convicted in 1983 of bombing a Bilbao power plant and killing Rafael Vega Gil, a local wine merchant, among other crimes. Fernandez spent most of his jail term in solitary confinement.

Fernandez's father visited him only once in prison. One reason, says Fernandez, was his father’s concern for his job in the local government. The other was distance: Fernandez served in nine different prisons far from his hometown.

He was released in 2005, and has since worked with local political parties and as an activist for Basque prisoners' rights.

Prisoners' return

A popular cause for Basque leftist parties is calling for the government to move political prisoners closer to home. Banners calling for the prisoners' return to local facilities dot walls, houses and balconies throughout Basque country and a January protest in Bilbao attracted 120,000 participants in a city of less than 400,000. There are over five hundred ETA members still in Spanish prisons though the group is thought to have less than fifty active members left.

The ETA of Fernandez’s youth was something else again. Then militants faced off against a stifling dictatorship that had been in power for nearly four decades. In 1973 ETA detonated a bomb in Madrid that killed Luis Carrero Blanco, Franco’s handpicked successor. Franco died two years later, and Spain slowly emerged from his shadow.

“When the dictatorship fell, ETA believed it was strong enough to not have to negotiate with Madrid,” explains Xabier Irujo, co-director of the Center for Basque Studies at the University of Nevada. “There they believed they could realistically accomplish their objective, which was Basque independence through armed struggle.”

Now the situation has switched, with ETA weakened and a Spanish government that is unwilling to negotiate.

“Madrid knows that ETA has no future, and they don't see the need to negotiate,” Irujo adds, “and the vast majority of Basques wish ETA had disappeared a long time ago.”