How to recycle a building, and school a president on climate

Loading...

In Argentina, a law requires climate change class for public officials

Named Yolanda’s Law in honor of Argentina’s first secretary of environment, the legislation requires at least 16 hours of instruction on topics including biodiversity, climate change, and sustainable development.

Since the law’s passage four years ago, 7,000 people – judges, office assistants, and a former president – have received training. Officials can be fined for noncompliance.

Why We Wrote This

In our progress roundup, we see how upending what’s usual brings results for the environment: In Grenoble, France, buildings on a seven-acre site were carefully deconstructed instead of bulldozed. And in Argentina, a law requiring training on climate change for public officials is meant to inspire informed decision-making.

The scientific community says support for science has eroded in the current federal government, but Yolanda’s Law has been implemented in all but one of Argentina’s 23 provinces.

The United Nations and others emphasize the importance of teaching climate change in schools. But Yolanda’s Law takes it further, advocates say, and is needed in a country with good environmental laws that are difficult to implement. “You need to make sure that environmental education gets to every sector of society, not only to children,” said María Aguilar, a climate activist at the nonprofit Eco House Global. “We can’t wait for those kids to grow up.”

Sources: The Wave, Progress Playbook, Nature

Replacing demolition with deconstruction lowers cost and waste for a circular economy

In 2021 at an old hospital site, the city of Grenoble achieved 98% recovery of materials – from bricks to door frames – in France’s first big experiment in salvaging. The goal is reusing instead of recycling.

At the site, deconstruction reduced carbon dioxide emissions by 373 metric tons (about 411 tons), the equivalent of flying around the world 39 times. In France, anti-waste laws require that most building waste is collected and processed. The construction sector accounts for 35% of the total waste generated in Europe, and the European Commission estimates 80% of related emissions could be cut with more efficient use of materials.

In the United States, Portland, Oregon, was the first city to require some deconstruction of homes in 2016, and several cities have followed suit.

Sources: Reasons to Be Cheerful, Grist

American women continue to narrow the gender pay gap

Last year, the Department of Labor reported that the average woman working full time earns 84% of what men are paid. However, Bank of America Institute data shows that female workers’ income growth has been faster than that of their male counterparts.

While there’s no single reason, women’s enrollment in four-year degree programs has been outpacing men’s since the early 1980s. Higher education means more opportunities for higher-paying work. But the analysis also saw wage growth in lower-paying service sectors that are dominated by women.

The bank’s analysis, which used data from small-business account payrolls, also noted that when women change jobs, their pay raises are greater than men’s.

Sources: Fast Company, Bank of America Institute

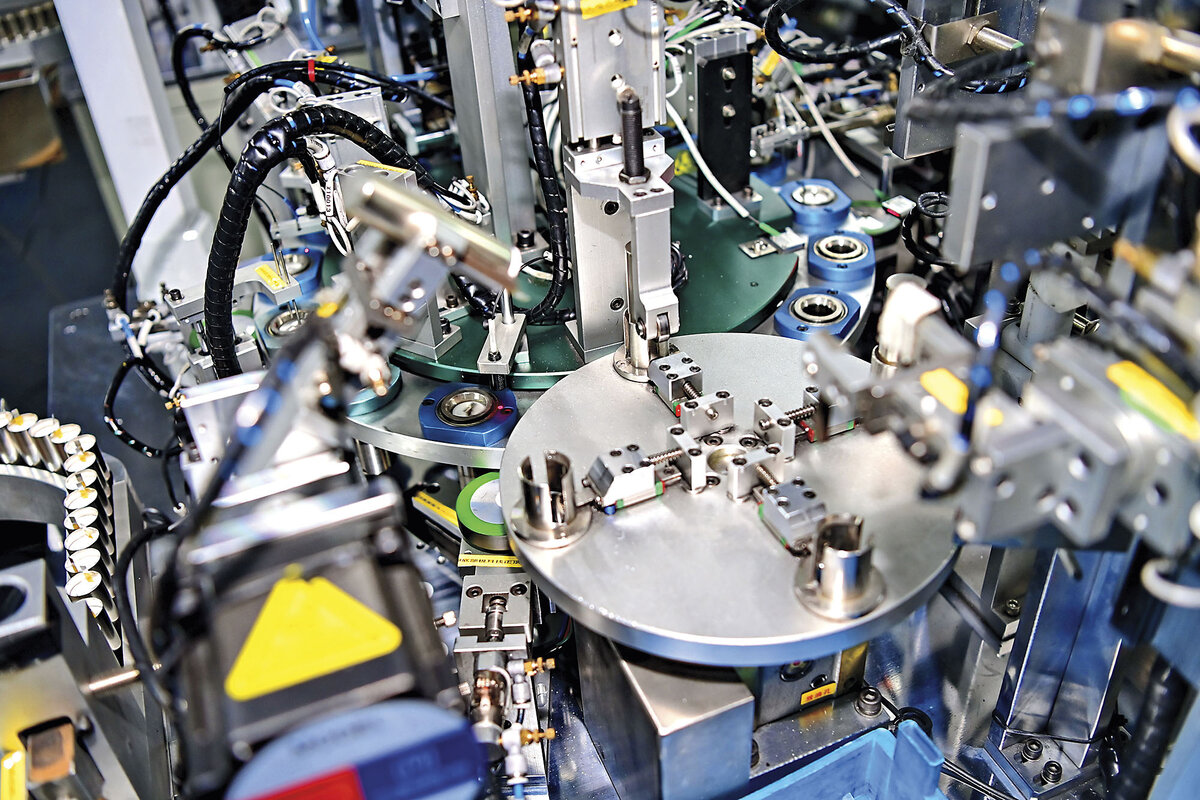

Researchers found a way to replenish the ions in lithium batteries, potentially extending their life

As a battery is used, it builds up deposits of dead lithium that, over time, diminish the battery’s ability to hold a charge. Eventually, the battery becomes unusable and typically dies by its 2,000th charge cycle, even as its internal components remain in good shape.

To combat that problem, scientists at Fudan University injected batteries with a solution of organic lithium salt. One type of battery, lithium iron phosphate, retained some 96% of its original capacity after more than 11,800 cycles.

Demand for lithium-ion batteries has tripled since 2017, and is expected to grow tenfold by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency.

Sources: Sixth Tone, Nature, Center on Global Energy Policy