Fault, justice, and firsts in court, nature, and the newsroom

Loading...

In Western Canada, advances in species preservation come thanks to the kind of cooperation between authorities and local populations we increasingly note here in our Points of Progress. And Nepal scores a first in conservation with a bird sanctuary accomplished through collaboration on provincial and local levels.

1. Canada

Two Indigenous groups joined forces with scientists, government, and businesses to triple the number of caribou in a British Columbia herd. Since the efforts began in 2013, the herd has grown from 38 to 114, thanks to a strategy focused on protecting vulnerable caribou like pregnant mothers and calves. Consulting firm Wildlife Infometrics designed pens lined with electric fencing for the ungulates. Members of the First Nations patrol the safe spaces to fend off wolves, and schoolchildren and local volunteers collect huge quantities of lichen from the forest to feed the animals. Once the calves are old enough, they are released into the wild and monitored.

Why We Wrote This

Our progress roundup includes a look at innocence. Unfortunately, not being at fault doesn’t guarantee justice, but a national record of exonerations is one step toward avoiding wrongful convictions in the U.S. In the U.K., not needing to declare fault in petitions to divorce is allowing for more harmonious proceedings.

The process is time-consuming and costly, and some conservationists oppose predator control as a conservation tool. But many see the successful population growth as proof that Indigenous strategies and modern science can work together effectively. “Western science has been heavily utilized, but it’s been led by Indigenous goals and ways of knowing,” said Carmen Richter from the Saulteau First Nations, which is working with West Moberly First Nations on the project. “Indigenous-led doesn’t mean it doesn’t involve other people.”

Mongabay, CBC News

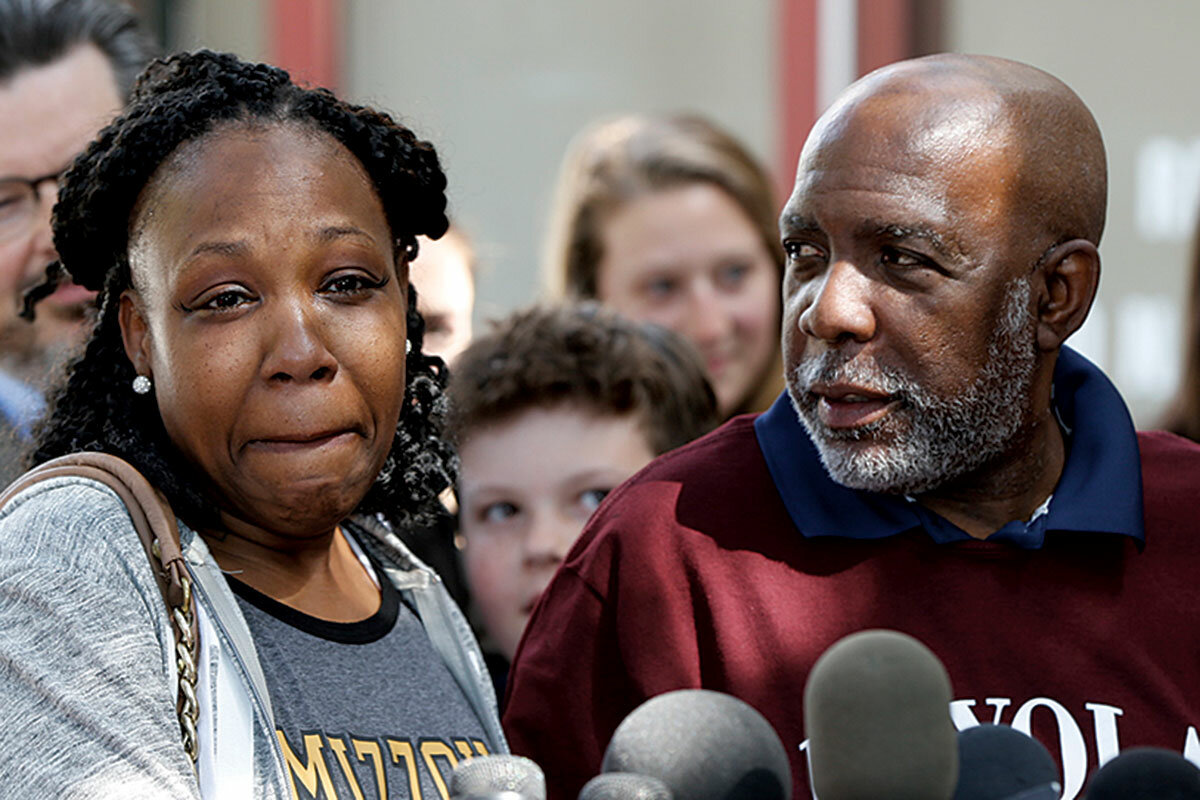

2. United States

In 10 years since its founding, the National Registry of Exonerations has recorded over 3,000 people being granted freedom, dating back to 1989. The 2021 annual report, released in April, includes 161 people exonerated in 2021, just under half of whom had been convicted of homicide. On average, the exonerated defendants spent 11.5 years in jail for crimes they did not commit.

The registry was launched by researchers from four universities in 2012, when there was next to no reliable data on exonerations in the U.S. While the data points to much larger problems in the criminal justice system, it also helps researchers and policymakers make more informed and humane decisions. “Our [policy] team is, quite frankly, entirely dependent on the registry’s website and dataset to both demonstrate the scope of the problem and humanize the faces of the wrongfully convicted,” said Rebecca Brown, director of policy at the New York-based nonprofit Innocence Project.

National Registry of Exonerations, Reuters

3. United Kingdom

Couples in England and Wales can divorce without finger-pointing, thanks to a new “no-fault” law. Before the new process for separation came into effect, an individual had to accuse a spouse of desertion, adultery, or unreasonable behavior to be able to petition for a divorce. Otherwise, they would need to separate for two years if both agreed on the divorce, or five years if not, before legally splitting. That requirement added additional emotional and logistical challenges to financial and custody decisions, say family law experts.

Now, no-fault divorces allow couples to separate with a simple statement that the marriage has ended, followed by a 20-week “reflection period.” Advocates say the changes allow for a more cooperative, harmonious parting of ways. “The end of the marriage doesn’t mean the end of being connected,” said Lydia, whose last name was not given. She and her partner of 18 years waited for the law to come into effect before going through a divorce. “It was important for us to find a way to progress [through] a sad situation in the kindest way possible and prioritize working together amicably over a win/lose approach.”

BBC, Metro.co.uk

4. Somalia

The first all-woman newsroom opened in Somalia. Sexual harassment is prevalent in Somalia’s media industry, and promotions – let alone basic respect – can be hard to come by for female journalists. Bilan, which means “bright and clear” in Somali, brings together a team of six led by Nasrin Mohamed Ibrahim, one of only a few female senior news producers in the country. “Never before have Somali female journalists been given the freedom, opportunity and power to decide what stories they want to tell and how they want to tell them,” wrote Ms. Ibrahim in an editorial in The Guardian, adding that Somali women are more likely to share their stories with other women.

The media house, which launched in April, produces news and features for TV, radio, and online, with an eye for issues like gender-based violence and women in politics and business. Bilan Media will provide its reporters training and mentoring from established journalists and offer internships to top female journalism students. The project is funded by the United Nations Development Program as a one-year pilot, with goals to extend and expand the program.

The Guardian

5. Nepal

The country’s first bird sanctuary was inaugurated, protecting over 360 species of birds in western Nepal. The habitats of species like the great hornbill and the Indian spotted eagle – already in global decline – have come under increasing threat in the region due to highway traffic, construction, logging, poaching, and hunting. The Ghodaghodi sanctuary spans 2,563 hectares (6,333 acres) of lakes, marshes, and forest in Sudurpashchim province, creating an essential wildlife corridor between the plains and the hills.

Nepal has no federal laws that would facilitate the creation of a bird sanctuary, so the provincial government drafted separate legislation to allow for the nation’s first site of its kind.

“Mere declaration of the area as a bird sanctuary is not enough,” said Trilochan Bhatta, Sudurpashchim’s chief minister. “It’s everyone’s duty to conserve the natural, religious and historical importance of this site.” Conservationists are hopeful the site, which sits close to the border with India, will attract Indian tourists.

Mongabay