Behind death penalty’s sharp global decline, a shift in attitudes?

Loading...

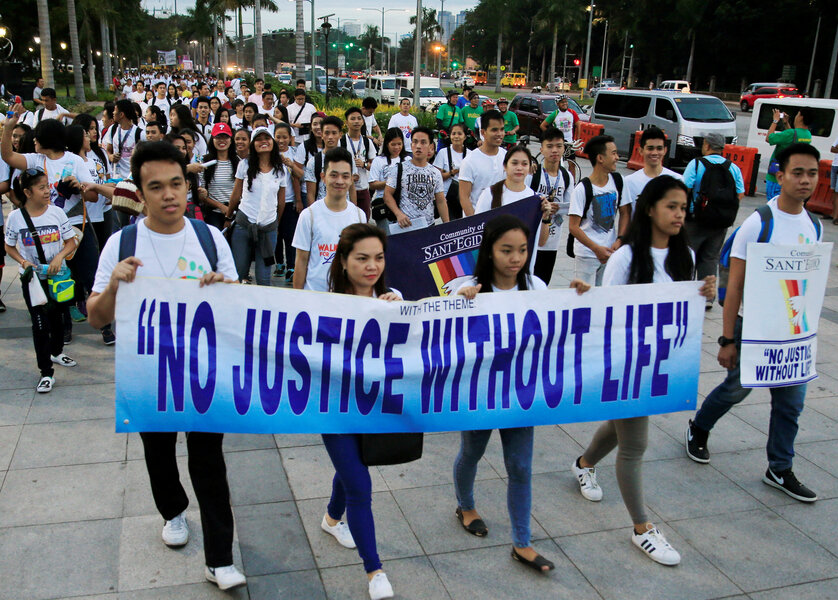

When the United Nations was created in 1945, eight countries had abolished the death penalty. Today, it has been abolished by law in 106 countries – and 36 more in practice.

In fact, in the past decade, an average of one country each year has repealed the death penalty, with Guinea and Mongolia doing away with it in 2017.

That’s according to a new report by Amnesty International that also suggests a change in global attitudes toward the death penalty, a handful of execution strongholds notwithstanding.

Why We Wrote This

Nowhere is diligence more required of justice systems than in the imposition of the death penalty. As societies carefully consider the stakes – and the effectiveness – of the punishment, more of them are backing away.

“When it comes to the death penalty, the progress the world has witnessed in the past decades is incredible,” says Chiara Sangiorgio, Amnesty’s adviser on the death penalty.

Amnesty recorded 993 executions in 23 countries in 2017, down 4 percent from 2016 and 39 percent from 2015. (These figures do not include thousands of suspected executions in China, Belarus, and Vietnam, which are state secrets.)

The United States carried out 23 executions in 2017, down from 98 executions in 1999, according to the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC).

Driving this sharp decline is a host of factors including concerns about human rights, discrimination, potential wrongful convictions, and its effectiveness as a deterrent. Some observers say that underlying it is a shift in attitudes on capital punishment.

“We are in a period of national reconsideration of capital punishment,” says Austin Sarat, a professor of jurisprudence and political science at Amherst College in Amherst, Mass., and an expert on capital punishment. “The death penalty is not just on the decline but [its proponents are] on the defensive.”

On the global stage, there are tens of countries where capital punishment remains deeply entrenched, including China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Pakistan, the countries that execute the most people.

In 2017, some 23 countries are known to have carried out executions, some in breach of international law, such as executing minors, people with mental disabilities, and those who “confessed” to crimes as a result of torture.

Despite serious concerns, these countries appear to be outliers. “The overall trend is very clear; more than half the world’s nations have abolished the death penalty,” said Salil Shetty, Amnesty International’s secretary-general, in a statement.

Numerous concerns underlie the growing opposition to the death penalty. “There is growing international consensus that the death penalty is a violation of human rights,” says Robert Dunham, executive director of DPIC in Washington, D.C.

In October 2017, Guatemala abolished the death penalty for most crimes after its constitutional court ruled that capital punishment violated principles in its convention on human rights.

In some countries, the decline in executions coincides with a drop in popular support. Some 49 percent of Americans support the death penalty in the US, the lowest level in more than four decades, according to a Pew Research Center poll. Some 42 percent of Americans oppose it, the highest level since 1972.

Concerns about discrimination are universal, as Amnesty’s report declared: “You are more likely to be sentenced to death if you are poor or belong to a racial, ethnic or religious minority because of discrimination in the justice system.”

In the US, multiple studies bear out such racial disparities. More than 75 percent of the murder victims in cases resulting in an execution were white, even though nationally only 50 percent of murder victims are white, according to DPIC.

Botched executions and exonerations also shake people’s confidence in capital punishment. DPIC figures show that since 1973, more than 160 people have been released from death row with evidence of their innocence.

Finally, many question whether the death penalty is an effective deterrent.

Ultimately, say experts, such concerns reflect introspection. “How a society punishes is a test of that nation’s values and commitments, and I see more and more people in the US and elsewhere worry that the death penalty does damage to the things they prize and value,” says Professor Sarat.

Mr. Dunham agrees: “Despite significant strife throughout the world, most countries continue to move toward more humane punishment and more humane enforcement of criminal laws. When we talk about human progress, that’s a good thing.”