Meet a new breed of prosecutor

Loading...

| CORPUS CHRISTI, TEX.

The new district attorney of Nueces County here in southern Texas strolls around the local courthouse in cowboy boots and a crisp brown suit with a colorful tie and matching pocket square, flashing a smile as wide as the grille of the Ford F-350 pickup he drives. On the surface, at least, he seems like your stereotypical Texas lawman – the one you see in movies wearing a Stetson and spurs, delivering justice and colloquial quips through a lip filled with chewing tobacco.

But then he tells you his name, Mark Gonzalez (the last name pronounced with a distinct Latino lilt). Then he might mention the trouble he’s had earning the trust of local law enforcement, in part because he’s listed as a gang member (he isn’t one, but more about that later). Eventually, he may talk about the raft of progressive changes that he’s beginning to implement in Nueces County, such as helping young offenders go to trade school instead of to prison.

There’s his background as a defense lawyer, his criminal record (he once pleaded guilty to driving while intoxicated), and finally this: the tattoo. Inked across his chest are the words “not guilty” – a bit of bravado from his defense lawyer days that he feels holds just as much relevance to his new job, which he won in a narrow election victory last November.

“I think every prosecutor should have in the back of their minds and in their hearts that everyone is not guilty until I prove my case,” he says. “I think my tattoo is something my office needs to always think about, and DA offices across the state and across the country” need to think about the concept, too.

Mr. Gonzalez is a rebel with a cause and a lot of legal clout. He is part of a new breed of prosecutor taking office across the United States with a reform-minded approach that sounds more Clarence Darrow than Clarence Thomas.

From Texas to Florida to Illinois, many of these young prosecutors are eschewing the death penalty, talking rehabilitation as much as punishment, and often refusing to charge people for minor offenses.

While their numbers are small, they are taking over DA offices at a crucial moment. Faced with crowded prisons and the high financial and social costs of incarceration, many states have been moving away from the strict law-and-order approaches of the past, often emboldened by justice advocates on both the left and right.

Yet in Washington, D.C., the tone is just the opposite. New Attorney General Jeff Sessions, backed by President Trump, wants to revive stiff sentences for drug offenders and tougher laws in general. Thus the new prosecutors could become crucial players in what is shaping up as an epic struggle for the soul of the US justice system.

“It does seem to be a new and significant phenomenon,” says David Alan Sklansky, a professor at Stanford Law School, of the new prosecutors. “It’s rare to see so many races where the district attorney is challenged, where they lose, and where they lost to candidates calling not for harsher approaches, but for more balanced and thoughtful, more restrained, more progressive approaches to punishment.”

Perhaps no one in the US is more important to dispensing justice than a prosecutor. Indeed, Robert Jackson, a Supreme Court justice in the 1940s and early ’50s, said a prosecutor “has more control over life, liberty, and reputation than any other person in America.”

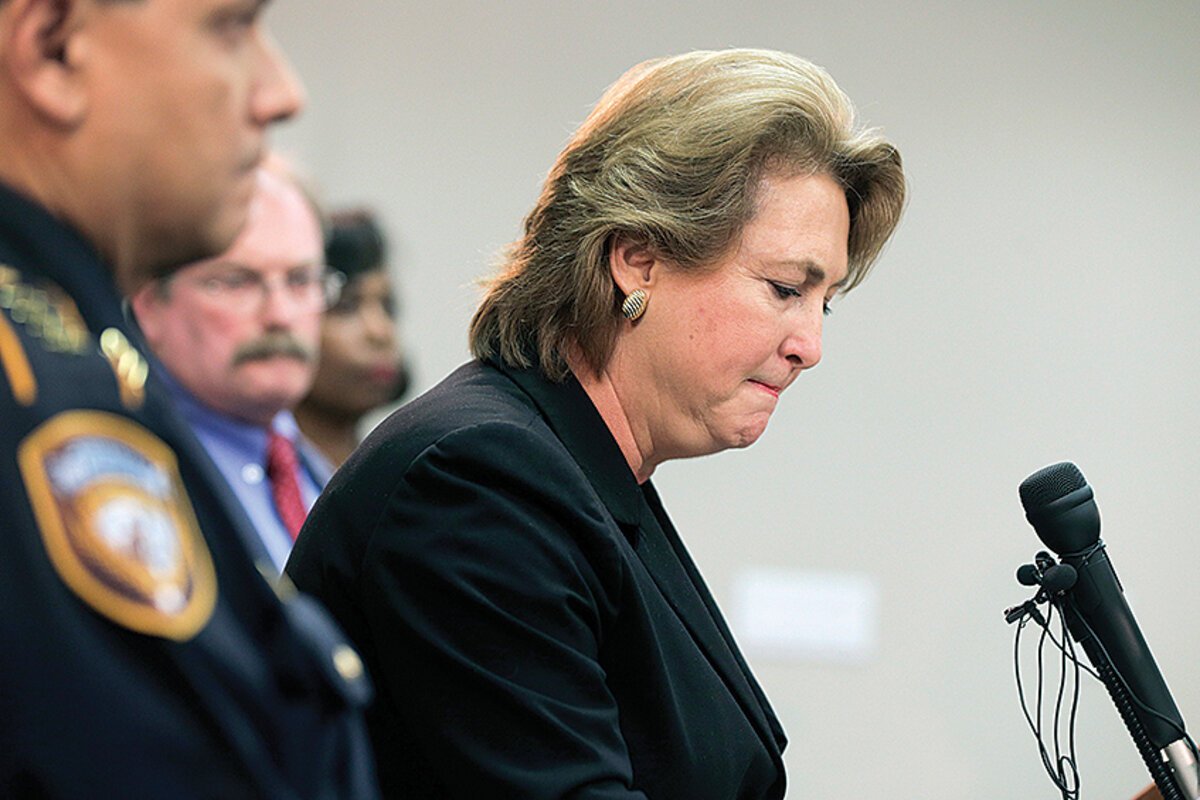

Prosecutors control the two most important decisions in the criminal justice process, experts say: levying charges and negotiating plea bargains, which is how some 95 percent of all court cases are resolved. As Kim Ogg, the new district attorney in Texas’ Harris County, puts it: Prosecutors “hold the key to the front door of the courthouse and the back door of the jail.”

Yet they have been one of the least scrutinized players in the criminal justice system. For much of the past century, it wasn’t unusual for district attorneys to stay in office for decades, winning reelection after reelection, often running unopposed, and trying to be as tough on criminals as possible.

But with the elections of Gonzalez and Ms. Ogg, and more than a dozen similarly reform-minded prosecutors, that appears to be changing. And given the discretion prosecutors enjoy in determining the fates of those arrested, the future of justice reform could be shaped by how this trend develops.

The new reformers, to be sure, represent only a fraction of the nation’s 2,500 district attorneys. But those numbers could climb as liberal activists such as billionaire George Soros increasingly target DA elections. Moreover, a generational divide may be developing, experts say, between these prosecutors – who came of age in an era of low crime – and an older generation of DAs shaped by the war on drugs.

Capital punishment has become a marker of how these new DAs seek to exercise their discretion in different ways. Aramis Ayala, the new district attorney in Florida’s Orange County, has received the most national attention for her refusal to seek the death penalty in any case, but she is not the only one. Beth McCann, the district attorney in Denver, is doing the same thing, and Larry Krasner, who is poised to become the next DA in Philadelphia, is an opponent of capital punishment as well.

Others are carrying out more subtle reforms. James Stewart, the district attorney in Caddo Parish, in Louisiana, took control of an office with a record of aggressive capital convictions and has quietly not gone to trial on a death penalty case since being elected in 2015. Kim Foxx, the new state’s attorney in Cook County, in Illinois, announced in March that her lawyers will not oppose the release of detainees from jails who can’t afford cash bonds of as much as $1,000. Ogg, who took over an office plagued by a recent history of unethical prosecutions, dismissed three dozen prosecutors in leadership positions and has hired a former judge to lead a newly formed ethics office.

Gonzalez is just beginning to define his reformist approach. He is still filing death penalty cases but hasn’t decided if he will continue to support using society’s ultimate punishment: He wants to wait to see what Nueces County residents say about it – particularly juries.

The new DA has refused to prosecute any misdemeanor marijuana offenses. Instead, offenders can get their case dismissed if they pay a $250 fine and take a drug class within 30 days. The policy has kept people with minor crimes from filling up jails but has made the county money, too: In the first four months, it has pulled in $320,000, wiping out a $3,000 deficit in the office’s pretrial diversion program.

Gonzalez has started an intervention program for first-time offenders facing misdemeanor charges for domestic abuse in partnership with a local women’s shelter. It requires those accused of domestic violence to sign a confession and attend a 24-week class on family violence in exchange for having the case dismissed.

He’s now trying to craft a similar diversion program for people arrested for driving with invalid licenses. He’s trying to partner, too, with local industries and trade schools on an initiative that would require younger violent offenders to graduate from a vocational school in order to get their cases dismissed.

“Jail isn’t always the answer. Convictions aren’t always the answer, especially if there’s history showing that convictions only show you’re going to get another conviction,” says Gonzalez. “We have some conservative people out there, but they’re interested in being smart and economic and efficient, and that’s how we have to move the courthouses into current times.”

Gonzalez’s views, like those of many of the new prosecutors, are rooted in both personal experience and shifting notions about criminal justice issues. One particularly formative moment for him came the night he had been at a party and, after having a few drinks, went out looking for a girl he knew. The cops found him first. They charged him with driving while intoxicated (DWI). He was 19.

Gonzalez didn’t know any lawyers, so he brought his mother to court with him. She told him that if he just pleaded guilty then the judge would be nice. He did so, and got the standard sentence: a fine, one year of probation, and 30 hours of community service.

That could well have been the end of the story, but then he saw a Navy pilot in the courtroom – charged with the same crime – get off with the help of a lawyer. Until then, he’d been considering becoming a dentist. “That’s when a light went off in my head: I’m going to be a lawyer so my friends don’t have to bring their mom; they can bring me,” says Gonzalez.

Some of his friends would probably need an occasional lawyer. Gonzalez grew up in tiny Agua Dulce, a poor farming community of about 800 people in southeastern Texas. He got his first tattoo, a portrait of Jesus, on his 15th birthday as a present from his father. His upper body is a wallpaper of ink now.

Previous generations of Gonzalez men had been oil field workers, but after graduating from high school, in a class of 25 students, he became the first person in his family to go to college. Construction work paid his way through Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, and becoming a father at 21 forced him to grow up quickly. Six years after his DWI arrest he had a degree from St. Mary’s University School of Law in San Antonio. He was the first in his hometown ever to go to law school.

“When you’re young, you do stupid stuff,” he says of his arrest. “I got caught for stupid stuff, and I got a chance. I think [other] people deserve that chance. But if they get that chance and mess up, my hand will be heavy.”

Gonzalez’s maverick image has been reinforced by the time he spends on the back of one of his Harleys (he has three of them and two other motorcycles). He is a member of the Calaveras motorcycle club, which some local law enforcement officials consider a gang. Hence his listing in their computer database as a gang member. Yet he proudly admits to being a part of the group – one that, he notes, does charity drives for kids.

Gonzalez’s work as a defense lawyer has shaped his unorthodox views as well. He often saw his clients overcharged by county prosecutors and pressured to plead guilty in exchange for lesser charges. “I just got angry at what I was seeing and the things that were going on...,” he says. “The [plea] deals we were getting offered were just outrageous.”

It’s a major reason he ran for district attorney. Unlike Ogg, Gonzalez didn’t receive donations from Mr. Soros in the campaign, which would suggest that the new progressive prosecutor movement isn’t dependent on the activist’s largess alone.

Yet Gonzalez has become a highly visible member of the new progressive prosecutorial class. Within weeks of entering office, he began getting invitations to join various national groups – from the John Jay College-based Institute for Innovation in Prosecution to Fair and Just Prosecution, a nonprofit led by former prosecutor Miriam Krinsky.

On this day, unopened boxes still clutter his office and a decorative cattle skull waits to be hung on the wall. Charismatic and energetic, Gonzalez moves from room to room, chatting with lawyers and cracking jokes (he tells a shorter colleague that he should celebrate his birthday at the local equivalent of a Chuck E. Cheese). When he’s not standing patiently in front of a judge, Gonzalez seems in constant motion.

He is also planning a trip to Seattle to learn about an ambitious diversion program, one that channels low-level drug offenders into treatment programs before they are arrested. This allows them both to get help and avoid having a criminal record. The initiative is being piloted by veteran King County Prosecuting Attorney Daniel Satterberg.

Still, as a DA in law-and-order Texas, Gonzalez recognizes that he can’t move too quickly with his reforms. “I’m not sure we’re ready for that,” he says of the Seattle program.

His approach so far mirrors that of Ogg, who is also a former defense lawyer. Both are members of Fair and Just Prosecution, and both are diverting those arrested for possession of marijuana – a simple misdemeanor offense – away from jail. Yet behind what many of these progressive prosecutors are trying to do lies a more fundamental goal: restoring trust in the law.

“In the last decade the American people have literally lost faith in the fairness of our justice system,” says Ogg. “If they think we’re rigging the system, or trying to force outcomes, then they’re not going to participate, and to me that is a huge threat to our democracy.”

A decade ago, that public dissatisfaction was already deeply embedded in Wisconsin’s Milwaukee County. The county had more than 24,000 people in jail at the time – twice that of the entire state of Minnesota – and John Chisholm was elected after the retirement of a district attorney who had been serving for 40 years in part because he said he would address that.

“There was a strong sentiment in the community that we were sending too many people to jail,” he says. “My argument was, if I can take an approach that increases public safety but reduce our reliance on jails and prisons, that’s potentially a good thing for everybody.”

Ten years and four reelections later, Mr. Chisholm thinks his philosophies may be gaining traction in the prosecutorial community. One reason is increased public interest in the criminal justice process, cultivated by national coverage of controversial police shootings and bipartisan efforts to reduce mass incarceration.

“The gut instinct response [to crime] is, ‘We’ve got to pass another law, a tougher law, get tougher on these individuals.’ That’s just a basic response to fear, and it’s worked for a long time,” he says. “I think people have come to understand the complexity [of the system] to a greater degree, and there’s a little less willingness to go to the knee-jerk responses.”

Maybe so, but the mood in Washington is much harder-edged. Attorney General Sessions has already restored mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, and personally asked congressional leaders to let him prosecute medical marijuana providers.

Sessions says that the recent upticks in violent crime in some cities represent “a dangerous new trend” and that the Justice Department “can’t afford to be complacent.” His concerns are rooted in his experience as a prosecutor in Alabama in the 1980s, at the height of America’s violent crime epidemic.

“They saw what the failure to respond aggressively in the ’70s led to, so they’re skittish about going to what they saw as soft approaches,” says John Pfaff, a criminologist at Fordham University who studies prosecutors.

The divergent philosophies of the Trump administration and some of these new DAs are a reminder that, with more than 2,000 prosecutors across the country, there is no cookie-cutter approach to fighting crime. “Hard” and “soft” approaches are constantly colliding and moving through the nation’s courtrooms in cycles. Indeed, many of the more liberal reforms being instituted today have been tried before.

What Ogg, Mr. Satterberg, and some of the other prosecutors are doing with drug offenders is essentially what local prosecutors in New York did in the 1990s. Back then – while the draconian Rockefeller drug laws were still in effect, no less – major DA offices across the state implemented programs to divert nonviolent felony offenders from prison to drug treatment centers.

“We didn’t wait for the Legislature to reform the statutes; we did it on our own,” says Bill Fitzpatrick, who has been the DA in New York’s Onondaga County for 25 years and is chairman of the National District Attorneys Association.

Nor have all these latest reforms come about just because Soros and other liberal activists began pouring money into local district attorney races. In Colorado’s Gilpin and Jefferson Counties, for instance, District Attorney Pete Weir has implemented multiple programs that emphasize treatment over prison and instituted specialty courts, including ones tailored to veterans and adults with serious mental health issues. Yet Mr. Weir, who was elected to office in 2012, beat a Soros-funded candidate in 2016.

“I think prosecution in general – and certainly my approach to prosecution – has evolved over the almost four decades I’ve been involved in the [criminal justice] system,” says Weir, who has also served as a staff prosecutor and judge. Weir argues that helping defendants is actually good for communities. It reduces the chances that they’ll commit other crimes.

“There’s an impression that a prosecutor is just the reverse side of the coin of a defense attorney,” he says. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Gonzalez certainly values having people with experience on both sides of the justice system. His office is rich in defense bar experience – not least in his top assistant, Matthew Manning, who worked with Gonzalez in private practice before he ran for district attorney.

Mr. Manning is a critic of the death penalty, and “pretty social justice-minded.” His office features framed news clippings of some of his major cases as a defense lawyer, a “Do the Right Thing” poster from Spike Lee’s film about racial tension, and a large painting of Martin Luther King Jr. getting arrested.

“I didn’t have some aspiration to be a prosecutor, but once I thought about the good we could do, I thought it was an extraordinary opportunity,” he says.

Gonzalez’s lawyers do prosecute aggressively – Manning got a gang member a 48-year prison sentence in a recent murder trial – but their defense experience informs their reform efforts to a significant degree.

“You can’t really fully appreciate how important it is to play fair as a prosecutor unless and until you stand next to somebody who could have their entire life taken away from them if the prosecutor doesn’t play fair,” says Manning.

While Gonzalez has made national headlines with a few high-profile moves so far – such as his marijuana diversion policy – these days most of his time is spent dealing with the bureaucratic minutiae that come with running a small government office. Jobs in local DA offices are among the lower paid positions in government, so turnover is high. In his first four months, Gonzalez lost three lawyers to more lucrative jobs. But on this day he is delivering a compelling pitch to one eager new candidate.

“One of the benefits we do have here is we’re being watched nationally – in part because I’m a defense attorney with a ‘not guilty’ tattoo on my chest – but also because of some of the things we’re trying to do,” he says.

“We’re trying to change things,” he adds. “I think everyone’s changing a little bit. The culture is changing.”

Correction: This article has been updated to correct the name of the nonprofit Fair and Just Prosecution.