15 under 15: Rising stars in cybersecurity

Loading...

Story by Sara Sorcher and photos and videos by Ann Hermes.

To see the project in its original form, visit projects.csmonitor.com/hackerkids

Kids born after the year 2000 have never lived a day without the internet. Everything in their lives is captured in silicon chips and chronicled on Facebook. Algorithms track how quickly they complete their homework; their text message confessions and #selfies are whisked to the cloud.

Yet the massive digital ecosystem they inherited is fragile, broken, and unsafe. Built without security in mind, it’s constructed on faulty code: From major companies such as Yahoo to the US government, breaches of highly sensitive or personal files have become commonplace. The insecurity of the internet is injecting itself into presidential politics ahead of the November election. In the not too distant future, digital attacks may set off the next war.

As they brace for an even more connected future, there’s a growing community of kids dedicated to fighting off the threat of cyberattacks.

The Christian Science Monitor's Passcode traveled across the country to meet 15 of these rising stars who are under 15 years old. They are part of a new generation of tinkerers and boundary pushers – many still lugging school backpacks and wearing braces – who are mastering the numerical codes that underpin the digital world. But they aren’t trying to break the internet. They’re trying to put it together more securely.

They are hunting software bugs, protecting school networks, and helping to safeguard electrical grids. They are entrepreneurs and community organizers bringing kids together to hack ethically. Unlike previous generations of hackers who were considered outlaws and deviants, these kids are now accepted by society and encouraged by adults.

After all, adults who laid the internet’s insecure foundation, have so far been unable to patch the security holes or stem the tide of cybercrime.

“There are smart, serious people thinking long and hard about these problems – and we don’t have the solutions we need,”says Stephen Cobb, a senior security researcher at cybersecurity firm ESET, who coorganizes a Cyber Boot Camp for teens. “I personally have to place a lot of hope and faith into the next generation. It’s the idealism of youth which may inspire alternative approaches to design and deployment of digital technology.”

As they work to fashion a better digital future, these wunderkindsare upending the longstanding cultural stereotypes that all young hackers are white, male, mischief-makers, prank-players and lawbreakers.

These are their stories.

CyFi

By day, the soft-spoken 15-year-old wears torn jeans and Converse sneakers to her experimental high school focused on technology in Silicon Valley. She’s an avid skier and sailor and carries her two-foot-long pet snake, a rosy boa named Calcifer, almost everywhere she goes.

But she has a secret identity: CyFi is one of the most prominent young hackers in the country.

To keep her alter-ego a mystery, CyFi refuses to reveal her real name when discussing her security research. She wears sunglasses to make it harder for people (or facial recognition algorithms) to recognize her features when she’s photographed. “You know how superheroes go by their superhero names, like Superman and stuff? It’s good to have a hacker name,” CyFi says, “so the villains don’t know how to get you.”

CyFi is not just hiding from nosy classmates or teachers. She’s responsible for the disclosure of security weaknesses in hundreds of products, from mobile apps to smart TVs, and worries companies might want to sue her for investigating mistakes in their code. Well aware of the Web’s dangers – digital thieves raided the database of the hospital where she was born and used her Social Security number and other information to buy a house and car under her real name – CyFi feels a personal responsibility to repair any digital security holes she discovers.

“As the internet gets even more connected to our homes and our schools and our education and everything, there’s going to be a ton more vulnerabilities,” she says. “Our generation has a responsibility to make the internet safer and better.”

CyFi first made headlines in the tech press at 10 for hacking Smurfs’ Village, an app that let kids to create their own virtual farms. She was giddy when she figured out a way to make her digital corn and berries flourish instantaneously – skirting payments and long wait times – by, essentially, fast-forwarding the time on her iPad.

CyFi’s mom, who works in the cybersecurity industry, walked in on her teaching a group of slack-jawed tweens how to break into their favorite games. Turns out, CyFi had unearthed a new class of previously undisclosed security weaknesses, otherwise known as zero days, spanning across all mobile devices. Criminals, CyFi’s mom explained, could take advantage of the app’s automatic trust of the device’s clock – a mistake most experienced developers wouldn’t make – to replace the time code with a malicious program to run on the app’s servers.

So CyFi emailed the companies that made the insecure games in hopes they would find a fix for her “Time Traveler” bug. “At first, I was a little bummed my favorite apps did fix it and I couldn’t cheat,” CyFi says. “But I thought, ‘it’s OK, because I am making the internet safer.’”

Instead of teaching her friends to cheat games for their own fun, CyFi took her talents to the vaunted DEF CON hacker conference in Las Vegas. She cofounded what’s now known as r00tz Asylum, a hub for ethical hacking workshops for kids, in 2011. With CyFi’s guidance, the 100 kids who came that first year banded together to discover 40 more vulnerabilities in mobile apps. The next year, they found 180. And CyFi led the charge to disclose these potentially dangerous security flaws to the companies, an effort that earned her a medal on stage in 2013 from Gen. Keith Alexander, the then-commander of the National Security Agency.

Today, as adults at DEF CON break into everything from ATMs to flying drones, r00tz is a “safe playground where they can learn the basics of hacking without getting themselves into trouble,” CyFi says.

It’s grown into a veritable security conference, drawing roughly 600 kids this summer in Las Vegas, with a nearly even split of girls and boys. This year at DEF CON, parents lined up each morning during the three-day event waiting to drop their kids off. There, they rip apart smartphones, laptops and other gadgets at the “junkyard” to learn how they work.

They solder hardware, wearing protective goggles to guard their eyes from the flames. They scramble to pick locks, learn cryptography and simulate how they would defend against a real-world cyberattack.

At r00tz, researchers will even set up the devices for the kids to try and hack. Breaking into one of Samsung’s newest smart TVs in a bounty program set up there when she was 12, CyFi says, “was a really important moment for me.”

She entered a string of code that turned on the device’s camera, which exposed the possibility of an electronic intruder spying on people as they sat on the couch watching “Game of Thrones.” Samsung awarded her $1,000 for the bug. “I think bug bounty programs are really important,” she says, “because it eliminates that worry of, oh, is this company going to be really mad about me poking around in their system?”

R00tz has become so big that it’s drawing corporate sponsors such as AT&T, AllClearID, Adobe and Facebook, and attracting volunteers from major tech companies. And to ensure the kids’ only hack for good, there’s a strict honor code: “The Internet is a small place. Word gets around, fast. Follow these rules at all times: Only hack things you own. Do not hack anything you rely on. Respect the rights of others. Know the law, the possible risk, and the consequences for breaking it.” That’s paired with encouragement. “R00tz is about creating a better world. You have the power and responsibility to do so. Now go do it!” the code says. “We are here to help.”

CyFi is already making a shopping list for next summer’s contests. She is budgeting for an array of internet-connected home devices, including speakers, toys, locks, security cameras, and even cooking devices for her army of kid hackers.

Shocked by the variety of connected devices her friends and their parents are bringing into their homes without considering their data security, CyFi wants to be an architect when she grows up and “integrate the Internet of Things into houses, but securely,” she says. “Whether it’s your blender or your oven or even feeding your dog, [our homes are] going to keep getting integrated.”

Kristoffer

Born in 2008, the year Apple launched its App Store, Kristoffer Von Hassel swiped before he walked. By age 2, a time when most kids are still in diapers, he had bypassed the “toddler lock” on his parents’ Android phone.

Then, at 5, young Kristoffer discovered how to outwit the parental controls on his dad’s XBox One, meant to keep him from playing violent video games like Call of Duty. With a few keystrokes, he figured out how to break in. “I was desperate to get into games which I wasn’t allowed to play,” recalls Kristoffer, now 8, from his San Diego apartment, holding a slice of pizza as an after-school snack.

It wasn’t a trivial discovery, either. Kristoffer, who looks (perhaps deceptively) innocent with his curly blond hair and board shorts, had uncovered a serious security loophole. When he found out, his dad Robert Davies, who works as computer systems engineer, laid out two options: They could expose the flaw on YouTube to alert everyone else to the secret way in, or reveal it to Microsoft, which makes the XBox.

Mr. Davies recalled their talk on a recent September afternoon, the sound of the ocean across the street filling the living room. Kristoffer thought about it, he said, and asked what would happen if bad guys learned about the workaround. “Somebody could steal an XBox and use your bug to get onto it,” Davies told him. “He said, ‘Oh no, we can’t have that, we’ve got to tell Microsoft.’”

Davies says he personally leans the other way, towards what’s known as the “full disclosure” approach: making the bug report open to the public and letting the chips fall. “So it’s interesting to see my son take the stark opposite approach, of working with the vendor.”

Microsoft fixed the flaw within a week. And Kristoffer became known as the world’s youngest hacker, when he made the company’s list of security researchers who found dangerous vulnerabilities in Microsoft’s products. “When I jammed the buttons I probably saved Microsoft’s b-u-t-t,” he says from his bedroom, filled with space posters and coding books.

“Thank goodness I found it, because it could have went into the wrong hands,” he says. “If hackers got control of all these internet-controlled devices, then we would really have no fun.”

Lately, Kristoffer says he’s been going after new targets, including tinkering with Roblox, an online gaming platform for kids. “In my free time,” he says, “I like to go on YouTube and watch exploit videos.”

Reuben

Ever since Reuben Paul was in the first grade, he’s known what he wants to be when he grows up: “A businessman by day, and a cyberspy by night.”

He’s not wasting any time. The lean, brown-eyed 5th grader from Pflugerville, Texas, is a chief executive officer at age 10 and is preparing for what he envisions as a life of adventure fending off America’s adversaries. Every weekend, Reuben, who is the country’s youngest second degree black belt in the Shaolin style of Kung Fu, practices his punches and kicks, and wields swords and daggers with fluid grace. While martial arts could be a bonus for any kind of future spy, Reuben is also sharpening his digital attacks and defenses. He has been learning to hack since he was 6 from his father, a former shark researcher-turned-computer security specialist.

As he earned international attention for his technical skills – speaking in front of audiences as large as 3,000 people from the GroundZero InfoSec Summit in Delhi, India to the RSA Conference in San Francisco - he had an epiphany. “I thought, ‘I’m learning about cybersecurity, but what about the kids that aren’t – the ones that are getting hurt in the cyberworld, and aren’t safe and secure?’”

So the ambitious kid with the nom-de-keyboard RAPst4r decided to blend his two passions – martial arts and cybersecurity – by founding a new nonprofit called CyberShaolin.

By creating an account on the CyberShaolin.org website, kids can watch short educational videos and take quizzes as part of his “Digital Black Belt” program. Reuben narrates the lessons on complex security topics using easy-to-understand analogies (one video, for instance, likens “the crazy letters and numbers” algorithms generate in cryptographic hashing to the mishmash of strawberry bits in a smoothie after a blender pulverizes the whole fruit).

Just like martial artists, beginners in Reuben’s program will start with white belts. “You’ll learn simple things: What is the internet, what is security, what is a computer, basically,” he says. Then, as the kids advance, they’ll earn more belts as they learn about basic attacks – such as phishing or wireless intrusions. Then there are blocks and defenses, “or, how to defend yourself using encryption and other types of things,” he says. After every video, the kids will take a quiz to make sure they really learn the material. By black belt, Reuben says, “you should know everything about security. You should be a security pro.”

Reuben’s family is already in talks with their local Texas school district about using some of the CyberShaolin videos in the curriculum. And cybersecurity company Kaspersky Lab is the organization’s first sponsor. Reuben’s family had considered making it a for-profit enterprise, but he insisted it should be a nonprofit. “We were first thinking we would make [kids] pay for it, but then I said, ‘No, education should be free for all kids to learn.’”

Something of a renaissance kid, who also competes in gymnastics and plays drums and piano, Reuben is so busy he does his homework for Harmony School of Science in the car. But he still makes time for video games.

It’s that love of gaming that initially led Reuben to start his other company, Prudent Games, when he was 8.

With the motto “Learn while you play,” Reuben makes apps that sell for up to $3 online. They include “Cracker Proof,” which he describes as “a fun way to learn about strong passwords,” and “Crack Me if You Can,” in which players learn about brute force attacks where hackers can instruct a computer to enter every possible password until one is successful. “We’re moving into an app generation,” Reuben says, “and you must be aware of the dangers.”

Mira

Mira Modi is an entrepreneur working to make the world safer one password at a time.

The 12-year-old New Yorker learned about Diceware – a technique used to create truly random passwords by rolling dice – when her mother, Julia Angwin, a journalist who writes about surveillance and privacy at ProPublica, did research for her book “Dragnet Nation.”

What started as a side hobby rolling dice for her mom’s friends in the summer of 2013 quickly turned into an enterprise so successful it left Mira’s wrists cramped. After word of her business made its way to news outlets such as Ars Technica and Mic.com, Mira’s business took off. She rolled dice at breakfast and while watching Harry Potter movies. She even had to quit Indian dance to make time.

The average person has 19 to 25 passwords. But easy-to-remember passwords are also really easy to guess – or crack. “If you were choosing your own password you’d probably associate it with something easy to remember, like, maybe your pet’s name,” she says, “and that’s easier to guess than just random words.”

To create the Diceware passwords, Mira rolls a handful of five dice. She looks up each combination in a 60-page, printed Diceware dictionary in a binder she labeled “top secret.” There’s an assigned word that corresponds to every possible numeric permutation the dice can generate. A random roll yielding 52325, for instance, corresponds to the word “row” in the Diceware dictionary.

The password she scrawls on a piece of paper for each customer is really more like a phrase, with the six words generated by the dice. Mira tells her clients to mix up the words with punctuation and capital letters to add extra security. She folds the passwords into envelopes and sends them in snail mail, which is, of course, much safer from hackers than sending an email.

Mira believes strong passwords are important but she admits that her security and privacy concerns are rare for her age group. Even her friends she’s plied with pizza to help with her dice-rolling refuse to take action. Some, she says, shaking her heard, even share their passwords on their social media accounts as a symbol of trust and friendship.

It’s clear her customers, though, are craving password security. She’s had nearly 2,000 orders. That would be a nice chunk of change for a kid – except, she realized, that after buying supplies like stamps, envelopes, and postage to places as far away as Spain and Tokyo, her margins thinned.

Plus, this small business owner is already learning the ways of the adult world: “Taxes are the devil,” she says, more than a bit grumpily.

Instead of flying her whole family to Harry Potter World as she’d hoped, the hyper-organized tween plowed her profits into a sticker-making machine and two planners to organize her business and school year.

And she’s already thinking about the future. “I want to be a lawyer in computer tech,” she says. “I want to get a computer science degree so I can fight crime. There’s only, apparently, six lawyers in the world who have computer science and law degrees and none of them are women.”

Paul

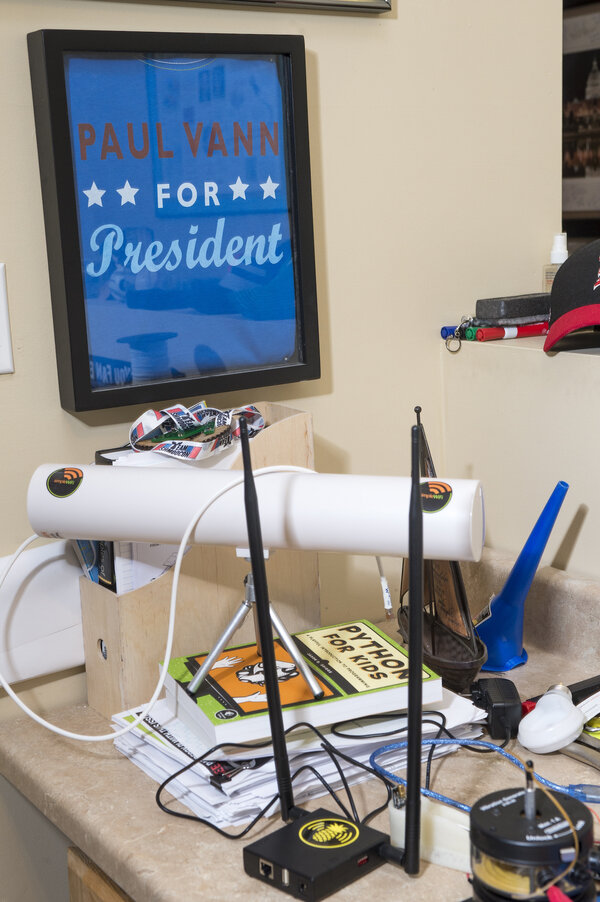

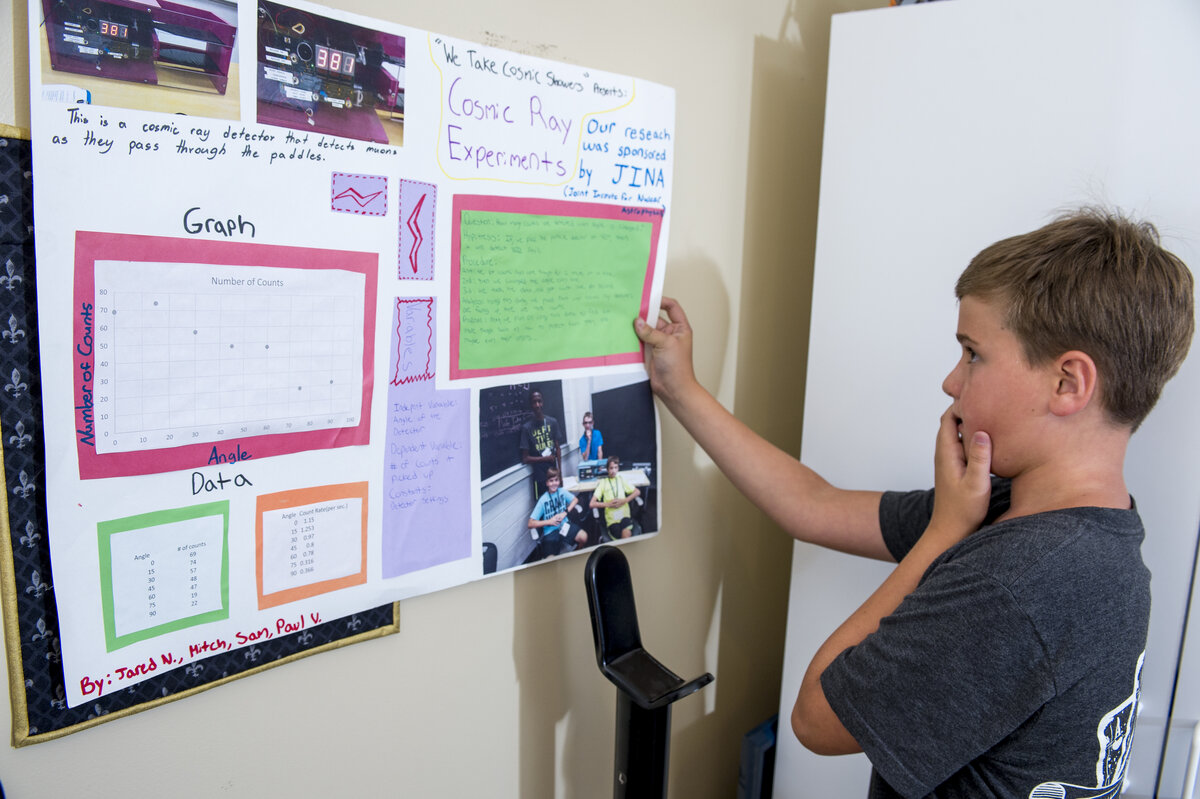

The upstairs bedroom of 14-year-old Paul Vann doubles as the headquarters of his company, Vann Tech. Next to his bed is a laboratory jam-packed with devices designed to break into Wi-Fi networks, data analysis software, a computer loaded with advanced hacking tools and a 3-D printer.

Paul, who skipped a grade and is now a sophomore at Chancellor High School in Fredericksburg, Va., pads around his room in bare feet as he discusses his latest venture: a new startup that tests companies’ security. He wants to build a product that will give companies insight into the landscape of digital threats facing them – and create a visual display of the areas of their systems electronic intruders are targeting. “Once I have the funding, I think we need a building and we definitely need more employees,” says Paul, who talks – and thinks – at fiber optic speed. “I can’t be the only one developing projects.”

On the side, he attends college courses in theoretical physics at the University of Mary Washington and takes free math classes online through the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – but he’s too young to get credit. The teen whose closet is chock-full of poster boards from science projects is also trying to build an “invisibility cloak” like the one in the “Harry Potter” books using theories rooted in acousto-optics.

Yet Paul, about to launch a round of grassroots fundraising for his company through Kickstarter this fall, laments one recurring problem in his foray into adult capitalism: getting grownups to take him seriously. “They don’t respect you as much as they would an adult,” he says.

Paul got into hacking after reading a book by self-described “break-in artist” Kevin Mitnick called “Ghost in the Wires.” It chronicles Mr. Mitnick’s escapades in two decades of hacking, which famously included stealing proprietary code from companies and snooping on the National Security Agency’s phone calls in the 1980s and ’90s.

But, Paul complains, “They never talked about how he did it.” So he downloaded online tools and started teaching himself through YouTube videos. “My first thing I wanted to learn was Wi-Fi [hacking] – that’s the easiest way you can hack someone if you’re not with them.”

The tutorials were successful. Paul was excited to find out he’d learned how he could break into all the Wi-Fi networks in a 3 mile radius from his bedroom. But the Key Club volunteer who is almost an Eagle Scout also wanted to make sure he didn’t break any rules. He asked his neighbors when they were over for dinner if he could actually get into their home internet.

“They said, ‘Sure, as long as you don’t do any damage,’” Paul says. As his parents and friends ate downstairs, Paul went to his bedroom laboratory. “I was finally able to break into something without getting into trouble,” he says.

Paul understands the consequences. “Hacking is fun for me. If I were to have malicious intent, I could get in trouble for it and lose the privileges I have,” he says. “It’s really important you consider ethics before you try to break into another system – and you want to make sure whatever you’re doing is not going to harm that system. And whatever you do, tell the person.”

Paul moved on to bigger challenges. After attending a cybersecurity conference with his dad where he learned about honeypots, decoy computer systems designed to look like an attractive target for hackers, he designed his own digital trap. His honeypot was meant to look like an online portal National Security Agency employees could use to get into a government network. “It’s almost like a trick,” he says of honeypots. “When hackers are trying to break into it, they don’t know they’re being hacked back.”

The 12,000 intruders from all over the world – China, Russia and even within the US – likely didn’t know that a teen in Virginia could have stolen their files or data. But Paul didn’t want to do that. He just wanted to see who might be interested in targeting a seemingly vulnerable US government system – and how they would go about it. His honeypot taught him a valuable lesson for his company: “You can use that data [from honeypots] to help prevent those attacks from happening later,” he says. He presented his findings last year to 200 people at DerbyCon, the largest southern information security conference.

After speaking there and at other cybersecurity conferences such as BSides Charm in Baltimore and Thotcon in Chicago, seven companies in cybersecurity, consulting and engineering fields approached Paul about internships. Too young to accept, he decided to launch his own research project: To track down the creator of the malicious software that allowed attackers to take down part of Ukraine’s power grid last December and turn off the lights for some 200,000 people. As policymakers and experts linked the BlackEnergy malware found on the infected systems to Russian hackers, Paul wanted to “figure out exactly who is attacking.”

He used sophisticated data analysis tools to track the Internet Protocol (IP) address of the computers that used BlackEnergy malware in the attack in Ukraine, ultimately discovering codes and phrases embedded in them. He connected them to an alias for a person he says is wanted in many countries for fraud or cyberattacks but has never been publicly linked back to BlackEnergy.

Even though the suspect was using a virtual private network that showed his computer’s location as in the Netherlands, Paul used geolocation features from data mining tool Maltego to pinpoint what he believes is his true location in St. Petersburg, Russia. DerbyCon accepted his research for a talk this fall, but Paul says he was too busy with high school to make it.

Still, Paul says his digital sleuthing “could be important to the cybersecurity community because it could allow for the BlackEnergy malware to be better identified and understood, and it could also allow for others to prevent the team from attacking Ukraine’s energy sector again.” If investigators were able to identify the suspect’s real name, he says, “we could prevent the flow of malware throughout the black hat hacker community in Russia.”

Andrew

At Del Norte High School, in the residential community just north of downtown San Diego, there’s a lot of school pride, says Andrew Wang, 14. “Don’t flock on the hawk,” he cautions, pointing to the school’s Nighthawk mascot emblazoned on sprawling school quad on which no superstitious student dares step foot. It’s not just sports stars and cheerleaders who get the attention. The flood of corporate money going into cybersecurity training programs for young people is helping morph hacking from what was once a fringe hobby into a team sport.

Last year, when he was in eighth grade, Andrew captained the middle school team that beat out more than 460 others from across the country to win a popular national cyberdefense competition called CyberPatriot. “Even though I may look like a ‘nerd’ on the outside,” says Andrew, laughing as he makes air quotes, “people will at least acknowledge that I have that competitive spirit.” Andrew, who plans to compete in the high school competition this year, is among 70 students in his district’s program. “Everyone wants to win.”

Organized by the Air Force Association, CyberPatriot tests the technical skills of tens of thousands of high school and middle school students with the goal of inspiring them to go into cybersecurity or other related technology and engineering fields. The Northrop Grumman Foundation – the philanthropic arm of the defense contractor – is the primary sponsor, and organizations such as Cisco, Facebook, Microsoft, and the Department of Homeland Security all contribute to the roughly $3 million a year it costs for the cyberdefense competitions, an elementary school education initiative, and dozens of cybersecurity summer camps. [Editor’s note: Northrop Grumman sponsors Passcode’s Security Culture section.]

Andrew and his team took on the role of IT professionals at a fake company and tried to keep its services running as attackers try to shut it down. It’s great real-world training, he says. “There’s an actual red team attacking you,” Andrew says. Winning “really depends on your ability to fix things on the fly.”

Andrew’s victory, though, meant more than heaping social media praise or even a gold medal. He learned the importance of cybersecurity at a very young age, when he made a dangerous mistake online. “When I was 8, I thought it would be a great idea to click a link from a random, unidentified sender,” he recalls. That one click allowed a hacker to sabotage the family computer. “I thought I had completely broken the system,” he says, “and my parents were really mad at me, too.”

So Andrew taught himself how to use security tools to eliminate the virus. “When I fixed it, all that doubt and worry went away. And I thought, ‘Maybe computers aren’t as hard as I thought initially,” he says. “Knowing I can protect myself makes me feel confident, and I know I can prevent infections from happening within the circle of my close friends and family.

With a cybersecurity workforce shortage estimated at 1 million jobs globally, Andrew says there is a new parity emerging in the tech world as adults realize they can’t solve all the problems themselves. “People who are experienced in this field,” says Andrew, who hopes to one day develop a new method of encryption, “are going to start being treated maybe not as kids, but as people who could change the future.”

Akul

During morning announcements, administrators at San Diego’s sprawling Del Norte High School will, every so often, instruct students to change their passwords.

For Akul Arora, 15, these loudspeakers were his rallying cry. “There have been a lot of attacks on the school district,” says the 15-year-old who honed his computer security skills training for the CyberPatriot competition and wanted to help out. He volunteered to help the school’s security pros over the summer and is finalizing a training program to teach the students and teachers about the dangers of phishing emails and viruses that “could get into a computer and ruin the entire district.

Each student has an account on the school’s network, says Akul, who sports big glasses and a trendy undercut hairstyle. And the attackers can get in largely because “some member of the network doesn’t know what they’re doing and they let something in.”

Akul is also expanding to teach kids at his former elementary school the basics, such as how to differentiate between secure and insecure websites. “Without dissing teachers at all, I think a lot of teachers are not very technology-centered. So I feel when they’re teaching technology, they’re just repeating what’s on a slide deck or materials given to them.” That message, he says, will resonate more coming from him. “My advantage with the students is that I’m of their generation and understand the problems they face in cybersecurity and that helps me connect with them better.”

As the internet started going mainstream back in the ‘90s, there was a lot of fear and suspicion surrounding hackers. The general public, along with companies and law enforcement, didn’t really understand the difference between those seeking take down systems or steal data, and well-meaning researchers who were exploring systems to ultimately fix dangerous security problems. Many researchers feared they would be arrested.

But today, the idealism and civic-mindedness of kids like Akul appears to be helping change the outside perception that all hackers are dangerous. “When you introduce yourself and talk about cybersecurity, I think people think how cool and interesting it is,” Akul says. “The idea that everyone who is in cybersecurity wants to do hacking is overrated. You don’t have to think of everyone in cybersecurity as someone who wants to break into systems, but someone who wants to do something for the community.”

Kryptina

When Kryptina was 9, she became one of the world’s youngest users of bitcoin. She was also very likely the first girl to use the digital currency.

Her dad, who goes by his hacker name Tuxavant and is now a Las Vegas bitcoin consultant, was one of its earliest adopters. He was looking for a way to teach computer and finance skills to his young daughter, so they started mining bitcoin together.

In 2010, Tuxavant started giving Kryptina a bitcoin allowance. “In the early days, it gave us a much more transparent view into what she was doing with her money,” he says. “There weren’t very many places she could spend it, so she would need to cash it out with us and we would know how she was spending it.”

When Kryptina wanted to buy “a stick of gum or ice cream or something,” Tuxavant says, “she would spend me back some bitcoin and I would give her cash to go and buy whatever she wanted.”

At the time, one bitcoin was worth just six cents. Now that she’s 15, it’s worth $635. “I remember a story about a guy buying a pizza with 10,000 bitcoin,” says Kryptina, who dyes her dark hair neon green and wears bright red lipstick. “I’m laughing because that would be worth so much right now, and he wasted it on a pizza.”

Today, bitcoin is much more popular: Tuxavant pays the bills for his office, landscaper and pool cleaner in bitcoin. Kryptina sets aside the electronic money for different financial goals, from her summer camp to saving up for a car. She even convinced her singing teacher to let her pay with bitcoin, which she loves so much she cowrote a song with her dad called “Love You Like a Bitcoin” and sings it to the tune of Selena Gomez’s “Love you Like a Love Song.”

With more places to use bitcoin than ever before, their family allowance system has evolved, Tuxavant says, “into a convenience and security issue.”

Unlike stealing a credit card, where anyone who has the physical card can steal your money, no one can spend your bitcoin unless they have the secret digital code that’s known as a private key. But security is a big responsibility. If users don’t properly protect their private keys, digital thieves could steal them and spend their money. Think about it this way: If someone can see where you bury gold in your yard, Tuxavant says, they can dig it up when you go to work the next day.

So Kryptina is learning about data security to protect her money, and uses encryption to protect her private keys and makes backups of her data.

Even though her friends throw caution to the wind when it comes to their security – “some people don’t even put passwords on their phones! My friends want to share their location of wherever they are,” she laments – her own security precautions border on paranoid. She’s not just worried about bitcoin thieves but data brokers or other predators who might be able to track her down.

She only uses fake names online and wears sunglasses to make it harder for people and facial-recognition technology to find her. (She and her buddy CyFi, for instance, don’t even know each other’s real names, even though they see each other every summer at r00tz.) She changes the way she types on the web to make it harder for anyone who might be monitoring her online to recognize her speech patterns. And of course, she never connects to public Wi-Fi.

For his school science fair project, Evan Robertson didn’t even consider making a volcano. The sandy-haired kid wanted to try something more original, he says with a sly smile. “I decided to test how many people care about their Wi-Fi security.”

Evan

The 11-year-old wearing a T-shirt that says “this is what awesome looks like,” exuded confidence from the stage at r00tz Asylum, where he presented his research this summer alongside the DEF CON hacking conference in Las Vegas.

Evan, who also performs in his elementary school choir and magic shows, used a Raspberry Pi – a small and affordable computer designed for people to learn programming – to create his own Wi-Fi hotspot. He hid the devices in grocery bags as he lurked in shops at local malls to test how many people would connect to a network just to get free internet connection.

To make his pop-up internet hotspot even less appealing for the masses, he wrote terms and conditions that, as he says “no one in the universe should agree to.” The terms explicitly said that anyone trying to connect to the network might have their data captured, changed, or redistributed however the administrator saw fit. They spelled out how that could include “reading and responding to your emails, and bricking your device” so it’s useless.

In case that wasn’t enough: “If you are still reading this, you should definitely not connect to this network,” the conditions said. “It’s not radical, dude. Also we love cats. Have a good day.”

A total of 76 people connected. More than half - 40 people - accepted the terms and conditions. In a surprising twist, Evan says the percentage who accepted in a separate test at the BSides San Antonio security conference, where people are at least in theory more aware of the risks, was very similar.

Evan, who won first place for his experiment at his school’s science fair, went on to nab the gold at the Austin regional science fair and presented his research at BSides before going to r00tz. He learned a big lesson: “People would rather have free WiFi than a secure connection,” he says. “People don’t read the terms and conditions – and security people do it just as much.”

Evan claims to be one of the rare few who do read notoriously long online terms and conditions in full and has tips for people who want to avoid becoming a victim of a network administrator with more malicious intent. Before you connect, Evan says, people should think about a few things: “Who controls these [networks]? What are they doing with that information, and are they selling it or spying on you?”

Mollee

Mollee McDuff, 13, kicked off this summer’s r00tz Asylum with her popular talk about ways to hack the Minecraft video game to give players more resources in the virtual worlds they create. She walked through strings of code on stage from behind her Macbook Pro with a sticker of the big-eared, purple Disney creature that was the inspiration for her hacker handle Stitch.

The girl with short hair wearing a hoodie and T-shirt that says “Periodic Table of Minecraft,” inspired the rapt kid-filled audience cheer as she proved her digital tricks could conjure up critical assets such as boats and mycelium. “The possibilities are endless with programming,” says Mollee, who’s from Colorado. She loves Minecraft, which is a “sandbox” game that gives players the ability to create new worlds with mansions or palaces or other resources. But she loves making “mods,” or modifications, to make the games easier or harder, even more.

An avid gamer, she wants to create her own games when she grows up. “I thought that its just a good way to get into programming because its pretty easy to do,” she says. “I figured, if I can get into this, then I can do bigger things later on.” Still, she says, when tinkering with any systems, “you have to be careful making sure it’s stuff that’s not malicious and you have to be doing it for good.”

Min and Isag

When Min Kim and Isag Kim (no relation) realized they were the only two students at their school who were signed up for CyberPatriot, the national cyberdefense competition, they never thought they had a shot at going very far. “I just wanted to go to nationals since I would get to go to Baltimore and stay at the hotel and miss school for a week,” says Min, 13, of last year’s middle school competition. “I was just going all out for that. But I didn’t really think we would go. We only joked about it.”

Usually, teams have four or five students, but at Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools – part of the Los Angeles Unified School District – these two high academic achievers were the only ones who dared take on the challenge. “We had to learn more and practice and study harder than anyone,” Min says.

Her school-skipping fantasy came true. The duo made it to nationals, beating out some 460 teams from across the country to get there. It was an intense challenge. Min was literally running around the table, manning five computers running the Windows operating system and Isag was juggling three with Linux. They were trying to keep the services running at their mock company while a red team of attackers tried to break into their systems.

“They [the attackers] would keep on leaving messages and we had to block them from logging us out of our computer,” Min recalls. “We were like, fighting them. When I first got hacked I was really scared and surprised because the mouse was moving, and I was yelling at Isag, ‘I got hacked!’ It was just going crazy.”

But it was also thrilling. The pair, who share a love for competition and Korean pop star G-Dragon, have known each other since third grade, and say it’s their bond together that helped them win the competition. Under pressure, Min says, “you have to talk to each other about what’s going on. We just talked to each other naturally, since we were close.” This was especially helpful, as Min says, “since we’re really shy around high schoolers or other middle schoolers most of the times.”

The competition also helped them build confidence. “Guys are meant to be energetic and more into adventure stuff and girls are kind of supposed to be like, princesses and very girly,” says Isag, who is 14. “It helps us know that girls can be just as good as boys.”

But this year, the program that manages the state-funded after school activities canceled the middle school CyberPatriot program, Min explains as she breaks into tears. Kids at their school aren’t joining the program, Isag adds, because they “don’t like studying anything.” But she believes it’s critical they start paying attention to these issues, even if it means more homework. “When you get hacked, you might not actually know [when] you have been hacked,” Isag says. “If you learn about cybersecurity, you’ll know – and how to prevent it.”

Min and Isag can’t compete this year, but they are shadowing the high school’s CyberPatriot team and taking on side projects. Min, whose family is moving to Texas, hopes to work for a cybersecurity company one day before she runs her own. She is now working to get an online certification in security from the Computing Technology Industry Association (CompTIA), a nonprofit trade association, while Isag is researching Linux and learning to hack so she can “protect the system better than any other people.”

If the program returns, Isag says, she has her eye on the prize. “I would like to aim for first.”

Emmett

Emmett Brewer, who just turned 10 and goes by the online moniker p0wnyb0y, first got hooked on hacking competitions at r00tz Asylum two years ago when he won first place and a free Chromebook. As he began to plan this past summer’s sojourn to Las Vegas, the quiet but competitive kid from Austin who wears a striped polo shirt that matches his red and blue sneakers, was excited to learn Facebook had released its own open source Capture the Flag platform, with the goal of making security education easier and more accessible.

So Emmett decided to give a talk about how to host these kinds of Capture the Flag competitions with friends. “I thought it sounded fun, as everyone could play and you could learn stuff,” says Evan, who has also contributed his own challenges to Facebook’s GitHub code-sharing repository. He gave step-by-step instructions for his 600-person audience at r00tz about how to set up the challenges. In order to win points, kids would have to find the answers to questions such as “who invented the internet,” or complete tasks like converting text to binary code.

A fourth grader, Emmett is already proficient in using penetration testing tools such as Burp Suite or Reaver. “Hacking is important to test out stuff and make sure it’s encrypted,” he says. “If you don’t have enough security, people can try to get in and mess around with your stuff.” When he grows up, he wants to be “maybe a penetration tester, because you try to hack the company you work for, and try to report those bugs.”

Blanca

Blanca Lombera, 15, had never considered a career in computers, until last year when she signed up for a cybersecurity and technology class on a whim.

Yet as an eighth grader at Lairon College Preparatory Academy, a public school where most students receive public assistance and learn English as a second language, computer security turned out to be a major source of inspiration.

Through the class taught by teacher Kathy Smith, who has led the charge to enroll her students in high-tech training programs that could elevate their job prospects down the line, Blanca attended a summer camp for hacker girls hosted by Facebook. She spoke on a panel for CyberGirlz Silicon Valley, an educational program at San Jose State University meant to guide middle school girls to look into computer science and cybersecurity and competed in CyberPatriot, the national cyberdefense competition. Students in Ms. Smith’s class learn to code at code.org, learn JavaScript at Khan Academy, and audit online college courses such as “The Ten Domains of Cybersecurity” or “Computer Science 101.”

Blanca, now a freshman at Andrew Hill High School, wants to go to college and then go into marketing at a tech company or be a software engineer. She would be the first in her family to do that. Born in Mexico, Blanca has lived in San Jose since she was 6. Her older siblings didn’t finish high school and her mom completed school until the 3rd grade. “There are a lot of jobs [in cybersecurity],” Blanca says. “Companies need people from other countries to fill them because they don’t have enough right here, and I’m living in Silicon Valley.”

Her career ambitions have kept her motivated despite the efforts of some kids to tear her down for earning recognition as a girl in tech. “This kid was like, ‘Oh, you’re a woman. You can’t go into cybersecurity. That’s just for men,” she recalls. “That hurt my feelings and I thought, ‘Oh, okay, I can’t do it.’”

Then, she says, “after I walked away, I was like, ‘Why do I have to listen to him? He’s not in security. He’s not in CyberPatriot. How can he know I can’t make it? It motivated me more to prove him wrong, and to show myself I am capable of many things, and you can’t let society define who you are. Nobody can tell you what to do.”

She also learned that nobody can tell her what not to do. When she discovered there weren’t any coding or cybersecurity classes or clubs when she got to high school, Blanca was really upset. “We were looking forward to learning more things and be able to go on to a career in technology,” she says. “I heard [some kids] were thinking about creating a club but they were coding by hand because the school didn’t supply them with any computers.”

But Blanca didn’t let that stop her. She asked a high school teacher if she would be willing to coach a CyberPatriot team – just in time for the fall registration deadline.

Blanca’s team is all girls.

Matthew

The day that reps from Facebook and cybersecurity company FireEye came to his cybersecurity and tech class at Lairon College Preparatory Academy was a defining moment for Matthew Nguyen, 13. “They were really enjoying their jobs, so that made me think coding was fun,” says the eighth grader in San Jose, Calif. “I thought, ‘If they enjoy it, I can, too.’” With the goal of being a psychiatrist when he grows up, Matthew is already learning cybersecurity to better protect his future patients. “If you were a doctor, or a psychiatrist, you’d want to keep your clients’ information secure,” he says. “Because if their information were to leak out, then I’d be in huge trouble.”

He’s now an advocate for digital security in his school, teaching other students the lessons he’s learning. “There are so many young kids who put themselves on the internet and they don’t know who is watching them. They just put things out there for anyone to see,” he says. “Like, anyone could easily find out where you live, whether you walk or drive home, and you could get kidnapped.”

Security, Matthew believes, is essential for all kids – not just those who plan to go into tech fields. Since almost every organization, from banks to retail stores, now relies on the internet and is customer information, the world will be safer if everyone understands the basics of security by the time they enter the workforce in a few years. “If we don’t learn about cybersecurity,” he wonders, “then who’s going to stop people from taking your information?”

Take action

One of our goals at Passcode, the Christian Science Monitor’s digital security and privacy section, is to provide readers with pathways to take action and get involved.

So if you’re a kid – or parent – interested in learning more about digital security, here are some resources to get you started:

R00tz Asylum: Summer ethical hacking workshops for kids in Las Vegas. A nonprofit cosponsored by the Wickr Foundation and tech companies is, according to its site, “a place where kids learn white-hat hacking to better the world.”

CyberPatriot: A national cyberdefense competition for middle and high school students organized by the Air Force Association. There’s also an elementary school education initiative, and dozens of cybersecurity summer camps.

No Starch Press: San Francisco-based book publisher with the goal “make computing accessible to technophile and novice alike.” Also publishes books and games specifically for kids leaning to code.

Code.org: A nonprofit with the vision that “every student in every school should have the opportunity to learn computer science.” Offers online courses including computer science fundamentals.

MIT Open CourseWare: A web-based publication of almost all Massachusetts Institute of Technology course content.

(ISC)²: While its Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) and Systems Security Certified Practitioner (SSCP) certifications are geared more toward professionals, the group offers an Associate of (ISC)² designation for those who pass the exam but don’t have the required work experience. They also offer paid, online training and flashcards as a free resource and some educational information just for kids.

Hak4Kidz: Chicago-based organization “dedicated to bring the educational and communal benefits of white hat hacking conferences to children and young adults.” Kids go for activities such as cryptography, coding, lock-picking, and other competitions in STEM and cybersecurity.

San Diego Mayor’s Cyber Cup: A cyberdefense competition open to all local high schools sponsored by the National Defense Industrial Association.

This multimedia project is part of Passcode’s security culture section. The goal of the Security Culture initiative is to empower people to understand the bigger picture of cybersecurity as it connects to some of the most personal parts of their lives: their job, their education, and the technology they use on a day-to-day basis. This initiative is generously supported by Northrop Grumman and (ISC)².