Iran nuclear deal: Implementation nears, but the sparring continues

Loading...

| Istanbul, Turkey

Just over five months since Iran and six world powers reached a landmark nuclear deal that was heralded as a historic choice of diplomacy over war, the tough rhetoric and frequent posturing that marked years of bitter negotiations persist.

News headlines remain full of claims and counter-claims linked to the accord – which limits Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for rolling back crippling economic sanctions – on issues as diverse as Iranian missile tests and American visa waivers.

And the battle between proponents and detractors has not abated: Those who struck the deal on both sides appear determined to fulfill its obligations even as hard-line opponents try to slow it down or halt it altogether.

US officials say Iran is moving faster than expected to dismantle key elements of its nuclear program, and Secretary of State John Kerry wrote to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Wednesday that Iran was taking steps in a “verifiable” way, and that “suspension of sanctions … is appropriate.”

That may mean first easing sanctions in January, much earlier than initial predictions of middle to late spring.

In Tehran, President Hassan Rouhani says Iran is fulfilling all its commitments and told Iranians that sanctions would be lifted in just over a month. He invited Iranians abroad and foreign companies to come and “profit from this opportunity,” and said “the way will be opened to greater cooperation with the world."

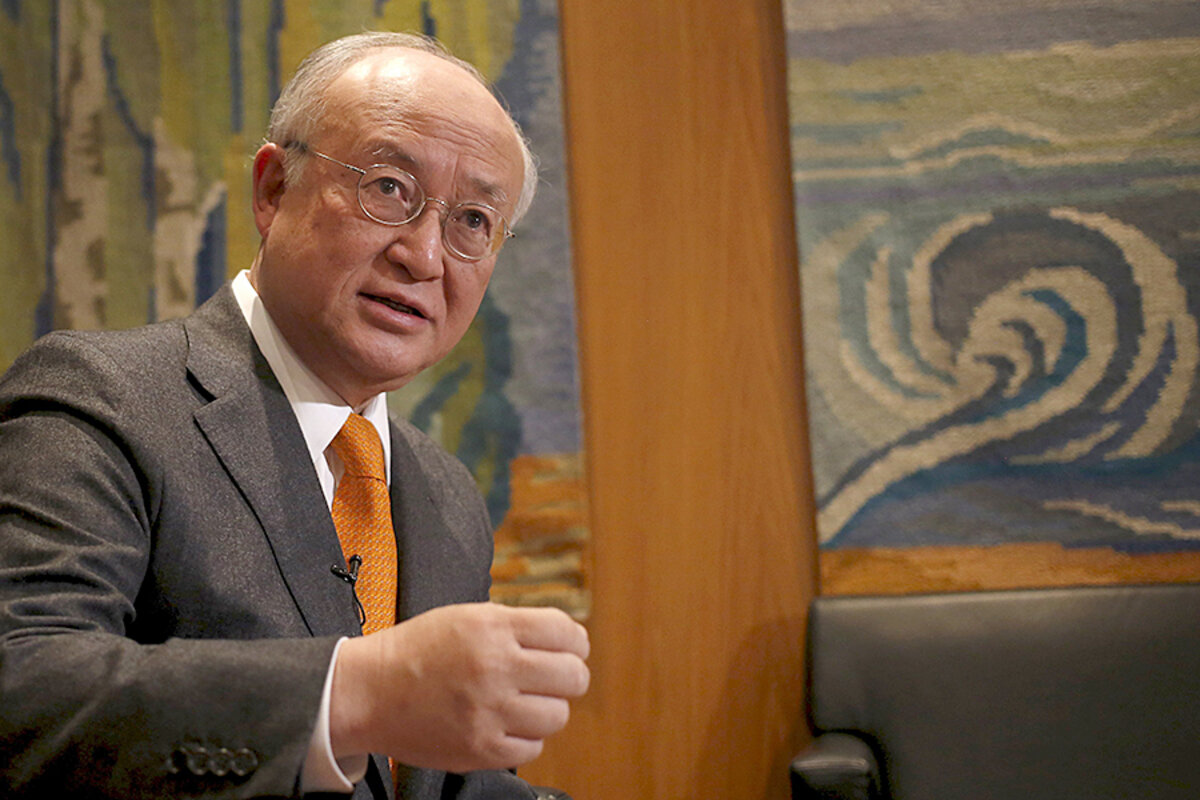

Yukiya Amano, the head of the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency, told Reuters on Wednesday that, “If everything goes well, it is not impossible,” that the deal’s Implementation Day – when IAEA verification and lifting of sanctions take place simultaneously – could happen by the end of January.

How much progress has been made since the deal’s signing, and what potential pitfalls remain? Some questions and answers.

Q: What are the most recent signs of progress?

US officials say Iran has already dismantled 5,000 of its 19,000-plus centrifuges that are used to enrich uranium, and expect that the remaining 8,000 or so still due to be mothballed will be put in storage in coming weeks.

Iranian officials say they will also complete in coming weeks reconfiguration of the heavy water reactor at Arak, pouring concrete into its core and ensuring that the upgraded reactor will not produce weapons-grade plutonium – a separate possible pathway to a bomb.

Iran is also expected to ship 25,000 pounds of low-enriched uranium out of the country by the end of December. That move “alone will dramatically lengthen Iran’s breakout time” if it wanted to build a bomb, according to Stephen Mull, the senior US official in charge of implementing the deal, speaking on Thursday.

“The fact that they are doing it rather [more] quickly than many expected, I think we have a challenge to make sure that every step is verified perfectly,” Mr. Mull said at the Atlantic Council in Washington, shortly after testifying before the Senate. “There are a lot of moving pieces that we will have to stay on top of in the coming weeks.”

What about allegations of Iran’s past weapons work?

The IAEA on Tuesday formally ended its 13-year investigation into possible military dimensions of Iran’s nuclear work, endorsing a “final assessment” that paves the way for the nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA, to proceed.

The IAEA concluded that Iran had carried out a “range of activities relevant to the development of a nuclear explosive device” in an organized way until 2003, and ad hoc up to 2009. Those activities, it said, “did not advance beyond feasibility and scientific studies.”

Critics and backers of the deal recognize that result to be a partial fudge: Some questions asked by the IAEA were not fully answered by Iran – which has always denied any nuclear weapons effort – and yet the July deal requires the case be closed on Iran’s past activities, as it now has been.

Do Iran’s missile tests affect the deal?

Iran test-fired a medium-range ballistic missile on Oct. 10, sparking anger in Congress and calls for more sanctions. The test violated a 2010 UN Security Council resolution that bans all Iranian missile tests.

A new resolution passed in July that endorses the deal – and will come into effect only when Iran is certified to have completed its steps – is less strict, with Iran “called upon” not to work on missiles “designed to be capable of delivering nuclear weapons” for eight years.

Iran says its missiles are not designed to carry nuclear warheads, and won’t constrain its program. Another test launch was reported in November.

Proclaiming that the October test showed a “blatant disregard for [Iran’s] international obligations,” 36 of the 54 Senate Republicans wrote to President Obama Wednesday, asking that sanctions not be lifted, Reuters reported. Other separate measures are already under consideration, such as designating the Revolutionary Guards a terrorist organization, or preventing the lifting of sanctions until Iran has paid court-adjudicated judgments against it.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has said that any new sanctions under “any pretext” would prompt Iran to walk away from the nuclear deal.

What do US visa waivers have to do with it?

In the aftermath of the Paris and San Bernardino terror attacks, House and Senate bills aim to tighten a visa waiver program that has largely benefited residents of Europe. But the measures require foreigners to apply for a visa – businessmen and tourists included – who in recent years have visited Syria or Iraq as well as Iran.

Proponents of the nuclear deal say any such law that includes Iran may violate the JCPOA, which requires all parties to not undermine provisions of the accord – in this case, disincentives for businessmen that could harm economic prospects for Iran in the post-sanctions era.

Proponents charge that Iran was deliberately written into the anti-terror bills to undermine the deal; US officials respond tentatively that JCPOA language is specific about the intent of the legislation, which is protecting US borders, not targeting Iran. Wording now may include a broad Homeland Security waiver for national security that, in theory, could be applied to Iran.