‘Motivated and inspired’: California inmates are improving mental health behind bars

Loading...

| Los Angeles

For years, the Los Angeles County jail has been known as the United States’ largest mental health institution.

An astonishing 5,901 people – nearly half of its population – struggle with mental health issues. In some parts of the jail, incarcerated individuals in quilted robes are chained to metal tables so they can’t harm themselves or others. For years, the U.S. Department of Justice has been monitoring the jail system – also the nation’s largest – to assess its mental health care.

And yet it’s making progress, particularly with a peer-to-peer program called Forensic Inpatient (FIP) Stepdown that the Monitor reported on four years ago. Since then, the nascent program has grown more than sixfold overall, spreading to the women’s jail. Incarcerated people trained as mental health assistants are helping hundreds of others with severe mental illness who are held at the same facility. The California state prison system – long under federal court orders to improve mental health care – is taking notice. Many familiar with the county program see it as a national model.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onFour years ago, the Monitor covered how two incarcerated men were helping their peers improve mental health at the Los Angeles County jail. Now their successful efforts are expanding.

The mental health assistants program, initiated by two people who were facing criminal charges, is “amazing,” says Alix McClearen, a former Federal Bureau of Prisons executive. “What I think is most amazing about it is that it was started by the peers themselves, instead of brought down from on high,” says the clinical psychologist. Top-down mandates often founder for lack of buy-in, she explains.

With the dismantling of America’s psychiatric hospitals, “Jails and prisons are the de facto mental hospitals in many cases,” says Dr. McClearen. She describes mental health care in carceral settings as a “crisis,” though not a new one: Forty-one percent of all state and federal prisoners surveyed in 2016 had a history of a mental health problem, according to the most recent numbers from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. That’s nearly twice the percentage of the U.S. general population in recent years.

Staffing of mental health professionals and physicians is a challenge throughout the correctional system. Peer support can’t replace those positions, says Dr. McClearen, but “It can fill some really big gaps.” It increases self-esteem and social functioning, while decreasing mental health symptoms and crisis hospitalizations. She’s particularly impressed that this program is flourishing in a jail, because jails have high population churn.

Sparkling clean in Tower 1

It’s “double scrub” Monday at the Twin Towers Correctional Facility in downtown Los Angeles. The towers, part of the county jail system, house the greatest concentration of men with severe mental illness – more than 1,200 who struggle with conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorder. Many are homeless. Their offenses range from murder to trespassing.

Here on the fourth floor of Tower 1, some of these men have been released from the jail’s FIP hospital into the FIP Stepdown mental health program. Here, the patients get professional psychiatric help. They learn basic hygiene, like toothbrushing. When allowed out of their cells to move freely in a common area, they work on communication and social skills. And they learn about the court.

“Our main goal is to get them ready for court,” says Sgt. Julian Flores, of the LA County Sheriff’s Department, a driving force behind the program. “The judges won’t want to see someone they can’t comprehend or [who] is unable to stand trial.”

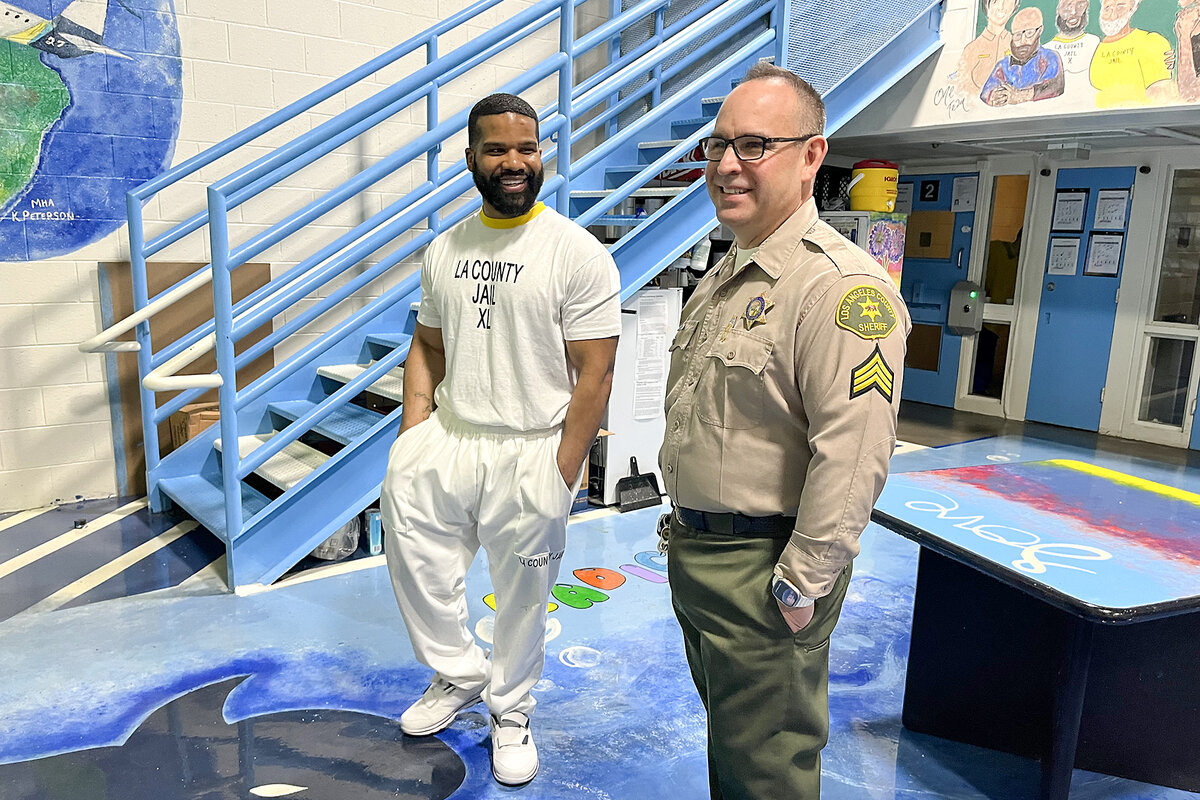

That’s where the double scrub Monday – and a unique role for Craigen Armstrong – comes in. Several years ago, Mr. Armstrong and another person now in state prison, Adrian Berumen, pioneered the idea of inmate mental health assistants. The duo lived 24/7 with peers in acute need and wanted to help them.

With the support of an on-site psychiatric technician and the county Sheriff’s Department (among others), the two men became a trusted bridge between the incarcerated patients and the professionals.

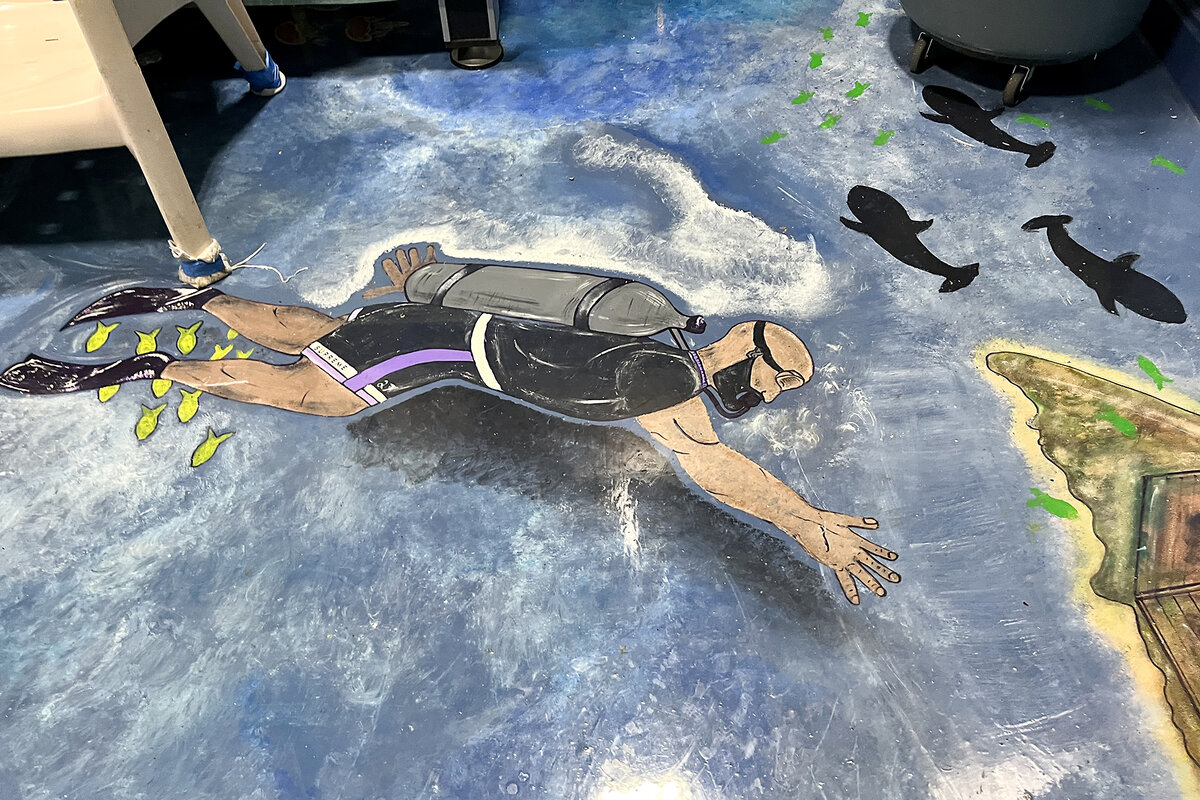

At 8 a.m. on a recent Monday, Mr. Armstrong led the patients in scrubbing their two-story pod of 16 cells from top to bottom. Then it was on to behavioral group therapy in the center of the room, with patients sitting on oversize soft chairs under a hand-painted banner that spells out “LOVE” in big red letters, followed by “each other better.”

“Double scrub is about personal responsibility, self-development,” says Mr. Armstrong, emerging from the gleaming module. “Whatever you do, do it 100%. And then it’s about teamwork. And daily hygiene. It may look like we’re cleaning, but it represents those three principles.”

Patients who complete their weekly checklists – from double scrub to group therapy to teeth cleaning – get rewards like personal radio and video time, pizza, and cheeseburgers.

Practicing what he calls the “magic” of love, Mr. Armstrong spends hours listening to them and talking them down from crisis. He knows the rewards that motivate each one, and he has success, for example, persuading them to take their medication (though he cannot administer it).

Mr. Armstrong says that his work as a mental health assistant has restored a sense of value to both his and his patients’ lives. It is “the main ingredient to rehabilitation,” because without that sense of value, it’s easier to degrade and harm yourself and others, he says.

Results have far exceeded expectations. When the Monitor reported on FIP Stepdown in May 2021, four mental health assistants operated in three pods, helping about 70 patients at Tower 1. At that check-in, self-harming had dropped to six times less than in other units, according to county mental health officials. Returns to the forensic hospital, a specialized psychiatric facility, were down by 35%.

Beyond the statistics, the results shone in the patients’ relaxed faces. They weren’t banging their heads against the wall as elsewhere in the jail. They weren’t throwing feces.

Rapid growth

Today, according to Sergeant Flores, the county jail boasts 24 mental health assistants at Twin Towers and 11 at the women’s facility. The incarcerated assistants’ work has expanded to 15 pods in Tower 1 and six pods in the women’s jail. Peer assistants help more than 400 patients in both facilities.

Additionally, the Sheriff’s Department has created 12 soft-furniture pods at both towers for incarcerated individuals who are more independent than those where the mental health assistants live.

There have been growing pains – and lessons, explains Sergeant Flores.

Not all custody staff have worked out; neither have all peer assistants. A committee of custody, mental health supervisors, and peer assistants has been created to recruit new assistants and address any issues that arise. The mental health assistants now undergo six months of peer support training by The Prism Way, a nonprofit specializing in support for people impacted by the justice system.

In December, the assistants at Twin Towers held a graduation ceremony for patients who had completed life-skills training in the FIP Stepdown program. It was a big deal, attended by local and state VIPs. Amid claps and joyful tears, 80 patients received certificates.

“These are guys who never came out of their cells,” says Cindy Shortt, co-founder of The Prism Way and a psychotherapist who attended the graduation. Now, “They’re walking around. They’re smiling. They’re accepting a certificate.”

The partnership among custody staff, the county’s correctional health department, and the peer assistants is “incredible,” she says. “It should be a national model.”

When jail becomes a mental hospital

Not everyone embraces this kind of peer support with such enthusiasm.

“Corrections is hard work, and not everybody goes into it because they believe in reentry,” which is one of the aims of peer support, explains Dr. McClearen.

Voters, too, may wonder why incarcerated individuals get free mental health care, while people not in jail pay for theirs. What is not considered, she explains, is the cost of not doing anything and releasing untreated people back into the community.

Keramet Reiter, a criminology professor at the University of California, Irvine, sees “tension” in the county’s program. Yes, it’s a “little beacon of hope” in a broken correctional system with insufficient resources, she says. At the same time, it’s symptomatic of a bigger societal problem in which people with mental illness often cycle through jail until their next arrest.

“What is the problem with our health care system and our emergency rooms and our treatment options that mean that the only place this [mental health program] is happening is in a jail?” she asks.

The state takes notice

On May 15, Mr. Armstrong, who helped start the peer mental health program, is facing retrial on multiple murder charges going back decades. Depending on the outcome, he could be transferred to a California state prison.

The state has faced litigation and federal scrutiny of its troubled prison mental health care for decades. In March, a federal judge appointed President Joe Biden’s former head of federal prisons, Colette Peters, to devise a plan to fix it.

In 2022, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation launched its own program to train people serving time for criminal convictions there as “peer support specialists” who mentor other incarcerated people. It’s part of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s prison reform initiative, called the California Model, which focuses on rehabilitation, education, and reentry. Peer supporters are expected to be working in all state prisons by June 2026.

So far, the program has trained about 670 incarcerated people in this work. Unlike those in the LA County jail, the peer specialists in the state system are paid.

But some worry Mr. Armstrong may go unnoticed in the vast state system.

“I hope that they would be able to take advantage of his knowledge wherever he ends up,” says Kerry Morrison, founder of Heart Forward, a nonprofit that promotes “radical hospitality” in mental health care, including at Twin Towers. She helped Mr. Armstrong and Mr. Berumen turn their manuscript on peer assistants, written with 3-inch pencils, into a book.

Ms. Morrison has been in touch with 10 trained mental health assistant alums now in the state prison system, but they aren’t being utilized, she says. Several told her that they have seen some of the very patients they cared for at the LA County jail now struggling in prison.

Prison “culture” makes it hard to implement the peer specialist program in state prisons, says Mr. Berumen, who co-founded the county mental health assistants program with Mr. Armstrong.

Now at California State Prison, Corcoran, he’s busy earning two associate degrees, but he hopes to use his experience to help improve mental health in the prison system. “I have so much to share,” he says.

California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, for its part, says it’s collaborating with Twin Towers and Ms. Shortt of The Prism Way to identify mental health assistants transferring to state prisons.

“There are active Mental Health Assistants from LA County Jail who are gainfully employed as Peer Support Specialists in CDCR,” department spokesperson Kyle Buis said in an email response to questions. He did not detail how many.

“Moved and motivated and inspired”

Last summer, Ms. Shortt coordinated a training session in which Mr. Armstrong from Twin Towers and another mental health assistant Zoomed in to talk with state prison nursing staff, among others. “They were very, very moved and motivated and inspired” by the presentation, she says.

At Christmas, a former mental health assistant wrote from prison to Ms. Morrison, the founder of Heart Forward. His skills came in handy one day in the prison yard, where he noticed an incarcerated person talking to himself and looking scared. The former assistant wrote that he approached the man, whom he described as incapable of conversing, and was able to walk the man to a care unit where he could get help.

“The fact that I was able to identify and help someone again gave me that feeling I felt at FIP,” the former assistant wrote. “I know I shouldn’t boast about it, but I’d be a liar if I said it didn’t make me feel good.”

“That also showed me how much I miss being a part of that program,” he added. “Anyone lucky enough to be part of it can understand what I mean.”

Editor's note: This story, originally published May 14, was updated to correct the description of Cindy Shortt. She is the co-founder of The Prism Way.