Iran sanctions: How much are they really hurting?

Loading...

| Boston

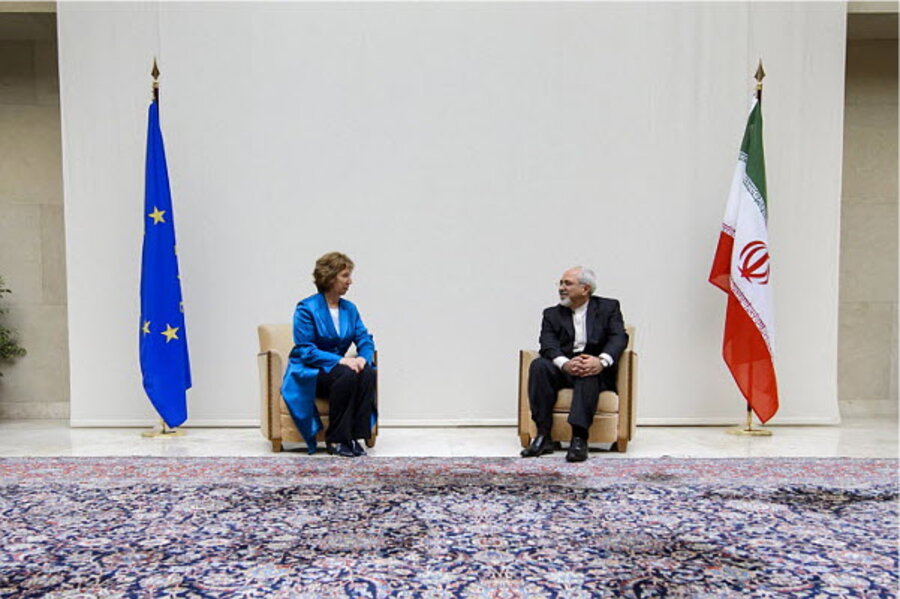

As world powers meet with Iran in Geneva today, their main bargaining chip is an easing of sanctions, the most painful of which have cut Iran off from the global financial system and put a chokehold on its oil exports.

Most observers say that the punishing sanctions have brought the Iranian economy to its knees, and that dire conditions were the catalyst for Iran’s rapid push for a nuclear agreement since the June election of moderate cleric Hassan Rouhani as president.

But there are others who argue that Iran is coming from a much stronger economic position than world powers are acknowledging, and scoff at the growing chorus warning of a collapse. The new leadership sees much to gain from making concessions to regain access to the global financial system – something that will play well among Iranians who want to return to business as usual.

"Iran’s economy is obviously doing very badly,” says Djavad Salehi Isfahani, a prominent Iranian economist and nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution who teaches economics at Virginia Tech. But “[t]he real question is whether it is in a desperate situation or not.”

A recent report from the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies and Roubini Global Economics estimates that Iran can afford only three more months of critical imports, and influential American voices are sounding the alarm for an impending humanitarian crisis.

"Their economy is in real trouble," said William Luers, a former US ambassador and director of The Iran Project, which seeks to improve relations between the US and Iran and counts former defense and intelligence officials, as well as leading academics, among its members.

Iran needs sanctions relief immediately, he said, noting that trade on the black market is burgeoning, and Iran is struggling to buy critical goods like medicine and medical equipment.

"It could become a humanitarian disaster in five years," he warned, speaking last week at an event organized by WorldBoston.

But Mr. Isfahani says Iran's economy is nowhere near collapse.

He acknowledges that the economy shrank by 3 percent last year and will likely shrink 2 percent by the end of this year, and that Iranians are feeling the contraction as prices rise and their real income falls.

But its leaders have not come to the negotiating table out of economic desperation, he contends. In fact, squeezing Iran out of the financial system could spur an industrial renaissance as the oil-dependent country begins producing goods it has imported from Europe and other industrialized countries for decades.

The new leadership is under pressure to remove sanctions for a different reason, he argues – an increasingly influential private sector that is tired of economic isolation.

“It’s a large economy, it’s a very complex economy,” he says. “I don’t really buy these arguments that Iran’s economy is on some kind of cliff and about to be pushed over by sanctions.”

“It has a way down to go before you get things like hunger, disease – things that are usually identified with economic collapse,” he adds.

A deflating cushion

According to the joint report from the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies and Roubini Global Economics – which has helped draft sanctions legislation and whose stated aim is to"prevent Iran’s leaders from acquiring nuclear weapons, continuing to support terrorist acts, and oppressing their own people" – Iran’s foreign exchange reserves are dwindling precipitously. The report says they have dropped from $100 billion in 2011 to $80 billion by July 2013, a figure that continues to dwindle. Only $20 billion of that is fully accessible.

Most of Iran's foreign exchange reserves, $50 billion and climbing rapidly, is locked up in semi-accessible accounts in countries that buy its oil but cannot transfer payment to Iran because of banking sanctions. As a result, Iran is rapidly accumulating unspent oil revenue in China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Turkey.

Foreign reserves serve as a cushion if a country ever runs out of revenue to cover imports. But according to Rachel Ziemba of Roubini, Iran has been paying for imports with its reserves for awhile.

Iran could use its overseas surplus to cover the costs of humanitarian goods, such as food and medicine, she says, but has opted not to do so in order to avoid undercutting domestic production. As a result, its semi-accessible foreign reserves continue to grow. On average, Iran generates $3.4 billion a month in oil revenue, $1.5 billion of which accumulates unused in overseas accounts every month.

"That doesn't mean there will be a balance of payments crisis right away, but it does leave Iran without a meaningful cushion," Ms. Ziemba said in a phone call unveiling the report. "Banks are increasingly financing the government."

But banks are struggling, too, Isfahani says. Iranian companies are finding it increasingly difficult to access lines of credit.

"The big banks are in trouble. Things are not rosy there," he says.

A worrying timeline

The fundamental question, said report co-author Mark Dubowitz, is whether "Iranian nuclear physics are beating Western economic pressure and diplomacy” – whether Iran is building up its nuclear capabilities faster than sanctions and negotiations can hobble its progress.

According to him, nuclear physics is winning.

Despite the rapid draining of Iran's reserves, Mr. Dubowitz estimated that Iran has enough cash on hand "to painfully hobble through" for at least a year – which is all the time it needs to build a nuclear weapon, from the day of making the decision to do so to the day it is completed.

That timeline is one that the US and Israeli establishments agree on, said Jim Walsh, a nuclear security expert and professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, at the WorldBoston event.

But, Mr. Walsh cautioned, that would be one year from the day that Iran manages to expel all international inspectors and start its centrifuges, which would take additional time – and so far there's no indication Iran plans to take that path.

Boosting local production

The question facing Iran's leadership: Should they make enough concessions to secure a lifting of sanctions, alleviating the complaints of Iranians who want their first-world medicines back and businessmen who want to rejoin the global financial system? Isfahani argues that it is the business community pushing Iranian leaders to strike a deal, not worries about an impending collapse.

Or will they throw their weight behind an industrial renaissance, allowing Iran to produce many of the goods it used to import?

“It’s anybody’s guess whether the Iranians are going to cry uncle or try to use their other option, which is to rebuild their economy,” Isfahani says. "Everything is becoming more advantageous to produce in Iran."

He draws a parallel to the 1980s, when sanctions and an arms embargo blocked Iran from importing weapons, prompting Tehran to build up its domestic arms industry in order to meet its military hardware needs and now boasts a formidable arsenal.

Unemployment is already declining and domestic production of many goods has risen in recent months, he says, although it will take years to fully adjust as it finds new sources for raw materials and builds up production facilities.

“Iranians have decided to try out removing sanctions so that they don’t have to make that adjustment. If they decide that this is too costly politically, that if they try to remove those sanctions, they’re going to lose the domestic fight [with hardliners]… the choice will not be to reduce their demands. They will say ‘OK, let’s go back to plan B. Let’s try to live with the sanctions and carry on.”