Iran's Parchin complex: Why are nuclear inspectors so focused on it?

Loading...

| Istanbul, Turkey

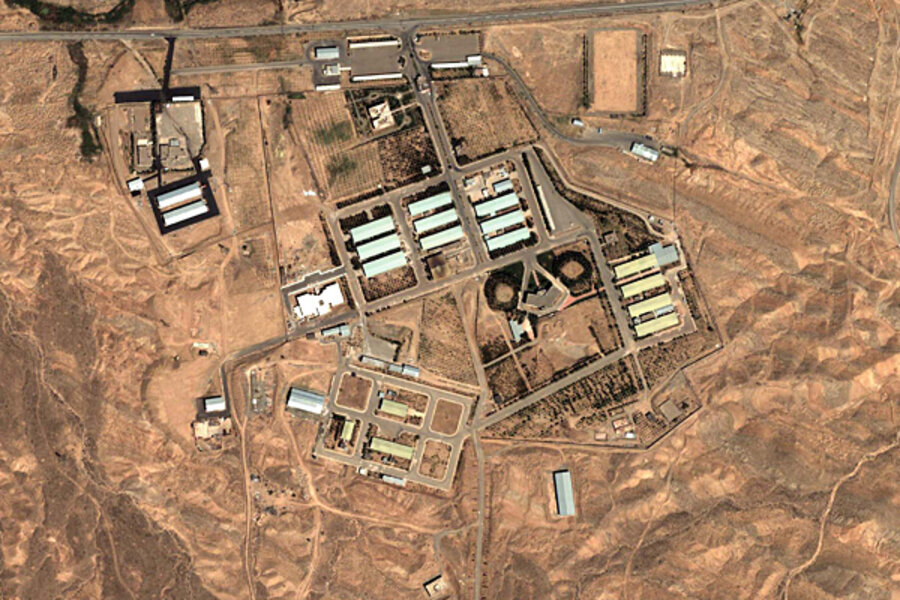

Parchin. In the annals of Iran's controversial nuclear program, the sprawling military base southeast of Tehran may hold clues to past weapons-related work – or it may not.

Parchin has been turned into a high-profile test case of Iran's willingness to be transparent by the United Nations nuclear watchdog agency, which says it has new information on past weapons-related activities there, and seeks access to the site for the first time in seven years.

But veteran inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) say the singular focus on visiting Parchin is a departure for the Agency that could jeopardize its credibility, considering the host of issues that remain between the IAEA and Iran. Also unusual is how open and specific the IAEA has been about what exactly it wants to see, which could yield doubts about the credibility of any eventual inspection.

"I'm puzzled that the IAEA wants to in this case specify the building in advance, because you end up with this awkward situation," says Olli Heinonen, the IAEA's head of safeguards until mid-2010.

"First of all, if it gets delayed it can be sanitized. And it's not very good for Iran. Let's assume [inspectors] finally get there and they find nothing. People will say, 'Oh, it's because Iran has sanitized it,'" says Mr. Heinonen, who is now at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. "But in reality it may have not been sanitized. Iran is also a loser in that case. I don't know why [the IAEA] approach it this way, which was not a standard practice; but they may have a reason."

The questions about Parchin come as Iranian Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Salehi said this week that Tehran is ready to resolve all questions about its nuclear program "very quickly and simply."

That promise comes amid a backdrop of threats of military action by Israel or the US, or both, to strike Iran's nuclear facilities; but also amid positive initial signals toward a diplomatic solution.

Iran and world powers – including the US, Russia, and China – last week resumed nuclear talks for the first time in 15 months. Both sides say concrete progress is possible at the next round on May 23 in Baghdad, if Iran agrees to limit its uranium enrichment and open completely to inspections, and if the world powers begin lifting crippling sanctions.

Previous inspections at Parchin

IAEA inspectors in January and November 2005 were given access to Parchin, a sprawling military base so large that it includes hundreds of buildings and underground structures.

At the time, it was divided into four geographical sectors by the Iranians. Using satellite and other data, inspectors were allowed by the Iranians to choose any sector, and then to visit any building inside that sector. Those 2005 inspections included more than five buildings each, and soil and environmental sampling. They yielded nothing suspicious, but did not include the building now of interest to the IAEA.

"The selection [of target buildings] did not take place in advance, it took place just when we arrived, so all of Parchin was available," recalls Heinonen, who led those past inspections. "When we drove there and arrived, we told them which building."

Since then, the IAEA says it has new information about a large explosives containment chamber installed in 2000. Experiments designed to simulate the first stages of a nuclear explosion, as suspected at Parchin, the IAEA stated last November, are “strong indicators of possible weapons development.”

IAEA experts requested visiting Parchin during two visits to Tehran in January and February, but were refused. IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano issued a terse statement, saying it was "disappointing that Iran did not accept our request."

Days later, the IAEA’s quarterly report on Iran explained that Parchin was part of a larger negotiation. It stated that "modalities" had not been agreed with Iran to satisfy "Iran's security concerns, ensuring confidentiality, and ensuring that Iran's cooperation included provision of access for the Agency to all relevant information, documentation, sites, material and personnel in Iran."

Why Iran is reluctant to allow access

Five Iranian scientists linked to its nuclear programs have been assassinated in Iran in the past two years, actions that Tehran blames partly on "leakage" of confidential information from the IAEA.

Ali Asghar Soltanieh, Iran's ambassador to the IAEA dismissed the Agency's focus on Parchin in early March, and said accusations about the military base were a “ridiculous, childish story they are making out of something which is nothing.”

Access to Parchin “is just one minor issue,” said Mr. Soltanieh, adding that the “surprise” IAEA request for visiting Parchin during the broader January-February talks in Tehran “jeopardized” Iran’s cooperative spirit.

Hans Blix, former chief of the IAEA and later of UN weapons inspectors in Iraq, has also expressed surprise at the focus on Parchin, as a military base that inspectors had been to before.

"Any country, I think, would be rather reluctant to let international inspectors to go anywhere in a military site," Mr. Blix told Al Jazeera English about Parchin in late March. "In a way, the Iranians have been more open than most other countries would be."

US intelligence agencies, and reportedly Israeli intelligence as well, have stated that Iran halted nuclear weapons-related worked in late 2003, and have made no current decision to go for a bomb. Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has declared nuclear weapons to be a "sin" and un-Islamic.

Skepticism about IAEA's Parchin claims

The Parchin data doesn't add up for Robert Kelley, an American veteran inspector of the IAEA who retired three years ago.

"It doesn't hold together, it doesn't make sense. So I can't understand why Amano would bet the Agency's reputation on [Parchin]," says Mr. Kelley, contacted in Vienna.

The hydrodynamic experiments described in the IAEA report are rarely conducted in a cylinder or any confined space, says Kelley, and would have used several hundred kilograms of explosives – not just the 70 kgs (154 lbs) the IAEA says the container was supposedly designed for in the 1990s.

"Would somebody in 1998 have been expecting to try to fool the IAEA in 2012?" asks Kelley. "That's kind of the logic of all this, that [the Iranians] are going to build a container because the IAEA is coming."

The 70-kgs figure is already “extremely high” compared to similar containment chambers around the world, says Kelley, and “is a red flag itself.”

Any inspection should clear up the confusion at Parchin, especially if uranium was used, because it could not be hidden from the IAEA’s sensitive instruments and detection techniques.

"If you do do an experiment in a container with uranium and explosives, that container would be highly contaminated," notes Kelley. "You can't get rid of the traces of uranium, and once you open the lid of the container, to clean it out and do another experiment, the building you're in will be totally contaminated with tiny traces of uranium that are very hard to hide."

The Associated Press in early March anonymously quoted "diplomats" accredited to the IAEA claiming that Iran had been trying to erase evidence of tests at Parchin, and sanitizing the site with haulage trucks and heavy equipment.

Heinonen says the commercial satellite imagery he has seen of Parchin showed "no immediate concern," and that heavy-equipment use was "far away" from the suspect building.

No 'real-time picture' of Iran's nuclear program

The IAEA regularly accounts for all of Iran’s declared nuclear material to ensure that none of it has been diverted for weapons use. Among that material is uranium, and its enriched versions that, when taken above the 20 percent that Iran has achieved, to 90 percent, is suitable for weapons.

But also in every report, the IAEA says it can’t confirm that Iran’s programs are entirely peaceful, because Iran considers intelligence reports provided by the US, Israel, and others – which detail alleged past weapons-related work – to be forgeries that it will not address further.

"I don't think that anyone has a real-time picture on the Iranian nuclear program; all the time you are dealing with information that is half a year old, one year old," says Heinonen.

Iran has also taken steps to protect it facilities, first by building the large Natanz enrichment plant underground, and then moving its most sensitive enrichment work to Fordow, a small site buried under a mountain and far less vulnerable to US or Israelis bombs.

Since 2009, Iran has also announced they would build 10 more enrichment sites. Why would Iran do it?

"It has a couple benefits: You distribute your assets, so if someone attacks they have to go to 10 targets in order to achieve what they want," suggests Heinonen. "Second, it takes a while for intelligence to find these places, so you can build them for quite a long time in secret before it would be found out."