A retired bishop transforms guns into garden tools to help youths envision peace

Loading...

| Winchester, Mass.

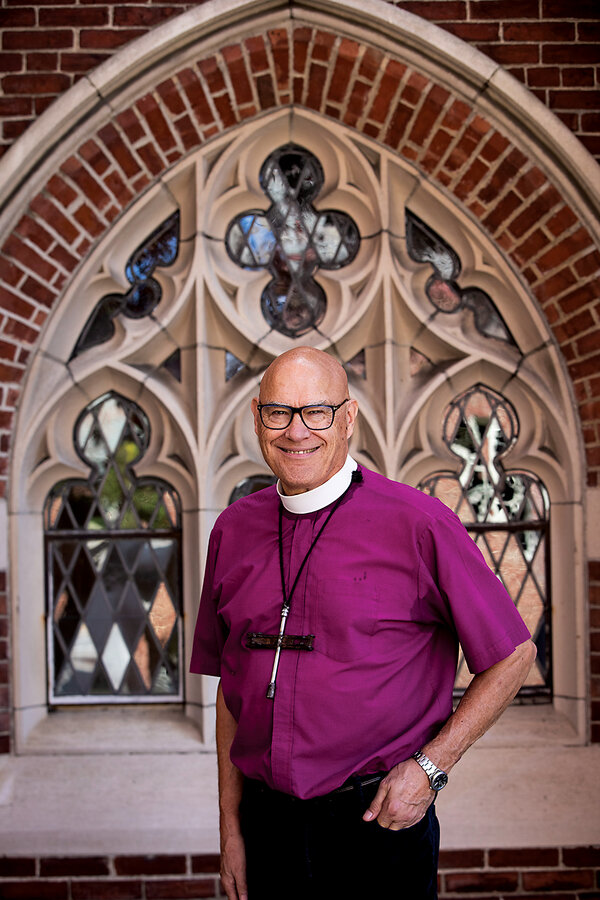

Retired Episcopal Suffragan Bishop Jim Curry ignites his propane forge in the courtyard of Parish of the Epiphany church. Slowly he heats the barrel of a dismantled rifle to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and then starts hammering the red-hot metal on his anvil. In minutes, a piece of once-deadly weaponry transforms into a humble weeding tool.

Bishop Curry then invites onlookers to try their own hand at making garden tools from firearm parts, using the forge that he takes with him to various communities in the Northeast region. With each strike of the hammer, participants mold a hopeful vision of a future without gun violence.

Before the demonstration, Bishop Curry gave a sermon explaining the mission of Swords to Plowshares (S2P) Northeast, a nonprofit that he co-founded a decade ago in New Haven, Connecticut. “At the forge, we hammer guns into gardening tools and art. We forge rings from shotgun barrels into hearts – symbolizing that the change we need begins in the transformation of our own hearts,” he told parishioners.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe toll of guns on cities across the United States is stark. Through blacksmithing, young people can find purpose and see an alternative to violence.

His work has inspired residents in Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Vermont to start their own independent S2P chapters, which host gun-surrender events in partnership with police departments. Law enforcement officials vet and dismantle the weapons, and then give the parts to the chapters for public blacksmithing demonstrations. Besides raising awareness about gun violence, the demonstrations help get young people interested in blacksmithing.

“One more gun is gone”

Montrel Morrison, who runs a youth mentoring organization in Connecticut, calls S2P Northeast a “safe haven and beacon of hope.”

“Young individuals impacted by gun violence need an outlet,” he says. “There’s something really transformative about breaking down a gun.”

Kam’eya Ingram, who spent the last two summers as a blacksmith with S2P Northeast, says that “When someone dies from gun violence, it’s like the world goes quiet.” But for her, hammering on the anvil fills the silence with a resounding release of emotions.

“You’re getting everything out at once,” she says, adding, “I feel like I’m bringing people peace – letting them know that one more gun is gone and that this [gun violence] might not happen to someone else.”

Bishop Curry has been a steadfast voice against gun violence, a calling shaped by his deep commitment to serving communities.

Born and raised in Oak Park, Illinois, he studied religion at Amherst College. He graduated in 1970 and started his career working in public schools in Huntington, Massachusetts, as a middle and elementary schoolteacher for 10 years. Yet he longed to serve the spiritual needs of his community.

That desire led him to the seminary in 1982, and, three years later, he was ordained as a deacon and priest in the Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut. He focused his ministry as a spiritual adviser, working in hospitals with families in Connecticut and addressing the devastating impacts of gun violence and suicide. By 2000, he was elected suffragan bishop of Connecticut.

His life “changed entirely,” he says, in the wake of the December 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, which killed 20 children and six adults. That day, he went to console the grieving community because Newtown was in his diocese.

After he became the officiant for the funeral of one of the children, Bishop Curry felt motivated to be a guiding light through darkness. “We always have the opportunity to claim hope,” Bishop Curry says. “That keeps me going.”

In early 2013, he joined other Episcopal bishops in Washington, D.C., and helped found Bishops United Against Gun Violence. Through that group, he learned about the Guns to Gardens movement, a network of nonprofits that repurposes unwanted firearms into garden tools and artwork.

Bishop Curry studied the basics of blacksmithing to start his own chapter in New Haven. “You have to try new ideas because the old ones don’t work,” he explains.

In 2014, he co-founded his chapter, S2P Northeast, with Pina Violano, a trauma nurse and nursing professor at Quinnipiac University. The group’s namesake peacebuilding mission comes from the Old Testament (Isaiah 2:4): “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning-hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.”

S2P Northeast has partnered with a Colorado organization called RAWtools on a nationwide gun-surrender program and, before the COVID-19 pandemic, taught blacksmithing skills to incarcerated people.

New Haven Police Chief Karl Jacobson says that S2P Northeast is an important ally against gun violence.

“I’ve seen far too many people lost to senseless violence in my career, so I’m glad to see guns which could fall into the wrong hands turned into something which helps our citizens,” he said in a statement.

“The real life of the forge”

For Bishop Curry, “the real life of the forge” has been to empower teens from New Haven through summer job opportunities. They are paid to transform guns through blacksmithing and help lead public demonstrations.

S2P Northeast recently received a hefty multiyear grant from the Connecticut Department of Public Health to expand its summer internship program to boost awareness of gun violence prevention.

Jared Sanchez, age 18, takes pride in being a junior blacksmith instead of working a teenager’s typical mundane hustle. In a single day, he can make seven or eight garden tools out of shotgun barrels. He has also created a heart necklace for his younger sister and a cross to sit beside his grandfather’s urn.

Growing up in Yonkers, New York, Mr. Sanchez saw “a lot of guns and a lot of gun violence,” he says. When he moved in 2021 to New Haven, he became jaded by the sights and sounds of gun violence and felt “numb to it all,” he adds.

After two summers serving as a blacksmith alongside Bishop Curry, Mr. Sanchez has come out of his shell and come into his own as a leader. Handling so many firearm parts has revealed to him the depth of the gun violence problem in his community and the work that must be done to combat it.

“The gun that you got rid of and we destroyed could’ve been the gun that kills,” he says. “People die every day from gun violence. We’re actually doing something about it.”