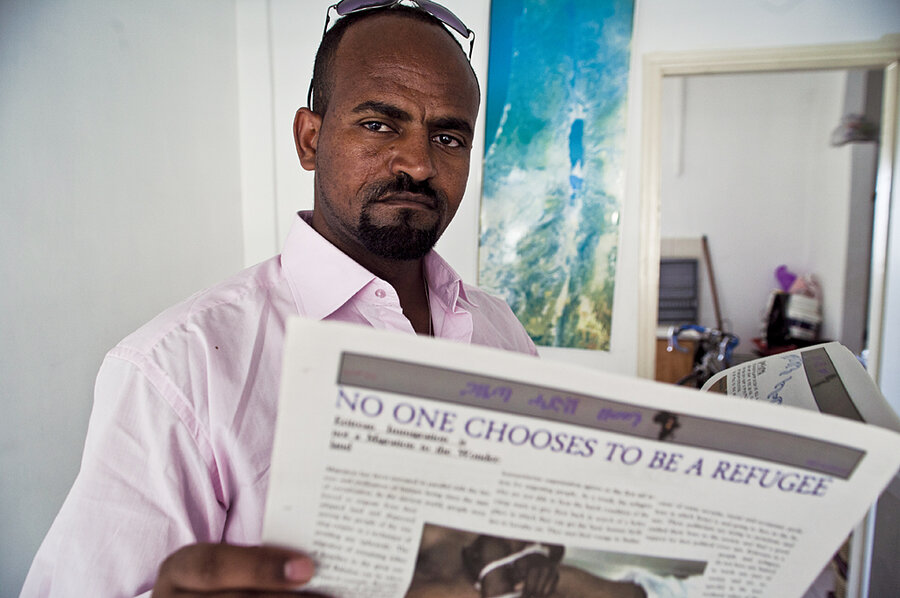

Kebedom Mengistu's little newspaper gives hope to Africans who've fled to Israel

Loading...

| Tel Aviv

In his tiny, shared rented room a stone's throw from the bustling, if somewhat run-down, central bus station in Tel Aviv, Kebedom Mengistu is busy putting the final touches on the layout of a newspaper he produces each month for Eritrean exiles who now live in Israel.

It's early September, and less than a week remains before the Jewish high holidays start here. As Mr. Mengistu points out, this particular edition of the newspaper he started just over a year ago is especially crucial.

Sitting on a simple wooden chair in front of a laptop computer, Mengistu, who arrived in Israel four years ago and is still seeking asylum here, explains that the paper must go to the printers today because it contains a special feature detailing what his African-born readers should expect during Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year holiday.

"It informs them that there will be no shops open on those days and advises that they should buy all their food in advance," Mengistu says.

His newspaper, called Hadush Zemen (New Century), is printed in Tigrinyan, one of the principle languages of Eritrea. It's aimed at the more than 40,000 Eritreans who have arrived illegally in Israel in the past five years.

The Eritrean government has been accused of multiple human rights abuses by the United Nations Human Rights Council and human rights groups, including requiring indefinite military service, torture, arbitrary detention, and targeting the family members of those who flee Eritrea.

Most Eritreans who have fled to Israel, like Mengistu, made the arduous journey from the East African country through neighboring African states such as Ethiopia, Sudan, or even Libya before crossing Egypt's Sinai Peninsula and sneaking over its border with Israel in search of a better life in the Jewish state.

"I want to provide my people with a place where they can tell their stories about the hardships of this journey and the challenges of their new lives here," explains the former accountant, who has left behind a wife and two children in Eritrea.

The eight-page paper, which he prepares as a PDF so that his Israeli printer does not have to deal with the Tigrinyan script, aims to highlight some of the social problems encountered by his community.

While for the past five years the arrival in Israel of thousands of African migrants – not only from Eritrea but also Ethiopia, Sudan, and numerous other countries – has been kept somewhat under the public radar, a recent spate of violent robberies and rapes has roused fear and anger among native Israelis, many of whom are calling for the immigrants to be deported en masse back to their countries of origin.

Those working to help the migrant community, however, decry such sweeping actions, arguing that Israel, a country essentially built by Jewish refugees from Europe, has a responsibility to help other refugees in need. They blame the lack of a clear government policy to help refugees and asylum seekers for many of the social problems the country faces.

Sigal Rozen, public policy coordinator of the Hotline for Migrant Workers, which provides Eritreans and other non-Israeli residents with skills and information to function in Israel, says that Mengistu's newspaper is just what the Eritrean community needs at this stage.

"The majority of the people only speak their own language, and while they might know a bit of Hebrew, they certainly cannot read or write in Hebrew," she says.

People arriving from Africa have to contend with a new culture and a different mentality, which often leads to misunderstandings with Israelis, Ms. Rozen says. Many immigrants are not aware of the rights they have or do not have in Israel.

Rozen lauds Mengistu's attempt to tackle these issues, calling the newspaper a real effort by Eritreans to "genuinely adjust themselves to life in Israel.

"I really hope it will help to minimize resentment against them, too," she says.

Mengistu hopes his newspaper can play an important role in that regard, he says.

"We have no political voice here at all, and we have no real status," he says. "This newspaper allows for conversation among the [Eritrean] community, and also lets Israelis know that we are not a threat, but, in fact, if we are treated right, we could one day become ambassadors for Israel."

Mengistu's newspaper also tries to reach those beyond the Eritrean community. There is a page in English for other members of the migrant community and one in Hebrew, written by veteran local journalist Lily Galili.

"I really believe that [the African immigrants and asylum seekers] were hoping to find the Holy Land when they arrived in Israel, or at least a place that would help them," Ms. Galili says.

She has been impressed by Mengistu's integrity and his enthusiasm in trying to help his community.

"I also wanted to help these people, and the best way for me is to contribute with my experience as a journalist," says Galili, a former reporter for the Hebrew-language daily Haaretz.

Impressed by Mengistu's work on his newspaper, Galili has helped him to secure a grant from the New Israel Fund, a foundation that supports community-based projects. The donation has allowed Mengistu to meet his printing costs and the growing demand for the paper, currently with a circulation of about 1,000.

He's now in the process of distributing his newspaper to other Israeli cities where Eritreans live.

"It looks like we are going to be here for a while, and it is time for us to learn how to live here properly, to get creative, and to fight some of the stigmas against us," says Mengistu, as he makes some finishing touches to the latest edition.

While his main objective is to provide fellow Eritreans with a better understanding of Israeli life, Mengistu would also like to use the newspaper as a forum to warn other Eritreans that life in exile can be tough.

"We are learning that often people's expectations do not match reality, and that can make people feel frustrated and let down," he says in his African-accented English. "I really hope we can find a way to send this newspaper to [refugee] camps in Sudan and Ethiopia where Eritreans are now living and let those who are contemplating coming to Israel know about the reality of life here."

With just 10 minutes to go before he must head off to work his shift cleaning a local lawyers' office – the newspaper does not provide him with a living wage – Mengistu fingers through previous editions and points out some of the issues and events he has tackled: a protest by local residents against the presence of African migrants in their Tel Aviv neighborhood; threats by Interior Minister Eli Yishai to send Eritreans and Sudanese migrants back to their former countries; and stories of rape, kidnapping, and extortion by those who made it across Egypt and into Israel.

"It's the only source we have in our language that can give us advice and information," says regular reader Tesfahon Yohanes, who runs an electronics store on the street between Mengistu's apartment and the central bus station.

"We don't speak Hebrew, Arabic, or English very well; we only know Tigrinyan, and the articles focus on stories specifically dealing with our community," he says, adding that it is the only newspaper in Israel that does this. (Israel has another Tigrinyan-language newspaper, but it concentrates on news of what is happening back in Eritrea.)

Another Eritrean asylum seeker here, Dawit Gebrakidan, points out that Mengistu's efforts serve to unite this community in exile.

"It does not only give us information, but it also gives us confidence as a community," Mr. Gebrakidan says. "Sometimes it's the only way we can find a link to each other and to our old life."

Helping refugees

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations worldwide. Projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

Below are three opportunities to help refugees, selected by UniversalGiving:

• USA for UNHCR provides assistance to men, women, and children forced to flee their homes because of war and persecution. Project: Help provide relief for refugee children in Somalia.

• Asia America Initiative provides assistance to Muslim and Christian children in the Philippines displaced by armed conflict. Project: Restore magic and laughter to refugee children.

• Global Citizens Network works with Tibetan refugee settlements in the Pokhara Valley of Nepal. Project: Volunteer at a Tibetan refugee settlement in Nepal.