For Ukrainians, war of survival is also a battle to defend their identity

Loading...

| ODESA, KYIV, KHARKIV, and DNIPRO, Ukraine

On its neoclassical exterior, the Odesa National Fine Arts Museum carries sadly the wounds of war: Windows blasted out by a Russian missile attack last November are covered with plywood, the mauve stucco walls pocked by shrapnel.

But the museum’s interior tells a different story. Instead of sadness, there is resoluteness, defiance, and roomfuls of national pride.

A main gallery is hung with paintings by past centuries’ Ukrainian artists, many of whom were banned from public display during the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, and even after independence in 1991.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onSince Russia launched its war, the Ukrainian people have seen, in the dismissal of their historical and cultural distinctiveness, and in the physical attacks on their cultural institutions, a coordinated campaign against their national identity.

One corridor displays the works of soldiers defending Ukraine on the front lines.

“From the beginning of the full-scale invasion, Russia has seemed in many ways to be more powerful on the battlefield than Ukraine, and this institution carries the physical evidence of that military power,” says Kateryna Kulai, the museum’s director since 2023.

“But here on the inside, we are working to show through art a different kind of power. I would say it’s the strength and determination of the Ukrainian identity,” she says.

“What we exhibit here can give an idea of why that identity has prevailed in the past,” she adds, “and why we keep believing in victory for Ukraine and the Ukrainian people in this war.”

The museum’s focus on national identity and memory is not unique. Ukraine is now in the third year of a war launched by an adversary – Russian President Vladimir Putin – who was motivated by the conviction that a Ukraine and Ukrainian culture independent of “Mother Russia” do not exist. In response, Ukrainians and their cultural institutions are redoubling efforts to bring to light aspects of national heritage, from art to literature and song.

As enemy forces target Ukrainian cultural sites – including churches and even the smallest of village historical museums – exhibits and discussions that invite the public to explore what it means to be Ukrainian are mushrooming.

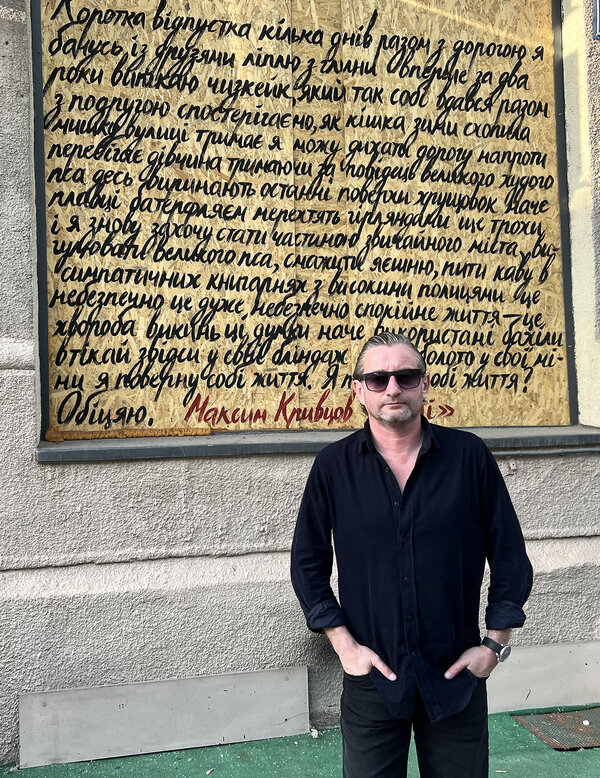

“When you look at the list of cultural and historical and educational sites [Russians] have struck and destroyed, it’s so huge that it’s become obvious to us that they are targeting them intending to erase something,” says Serhii Zhadan, a prominent Kharkiv writer who in intellectual circles has defended Ukrainian culture against Russian dominance for years.

“That adds a different dimension to what is already a fight for survival,” he says. “It becomes a battle for our identity and for our cultural independence.”

Protecting identity

For some, that battle makes exploring and asserting national identity a key part of Ukraine’s war effort.

“I would compare all these projects around the country reaffirming who we are and the values we are fighting for to a kind of shield, a layer of protection over our identity and memory,” says Andrii Palatnyi, curator at the Museum of Civilian Voices, a multimedia exhibit of average Ukrainians’ wartime experiences that was recently shown in Kyiv.

“After more than two years of war, we understand that Russia’s aim is to destroy much more than the physical Ukraine,” Mr. Palatnyi says. “We see the massive effort of reidentification Russia is undertaking in the areas it has occupied, like Mariupol.”

And in that context, he adds, “These public exhibits and activities become another part of our national defense.”

The reemergence of Ukrainian culture and identity from Russian domination predates the full-scale invasion and is largely the work of a generation that grew up in an independent Ukraine. Yet it was an eastward-facing country in which Russian language, history, and literature were not just preferred but imposed, for example in schools.

“Russian was what you spoke to be accepted in society. Ukrainian was for the rural people, the uneducated,” says Alina Stamenova, founder of Pomizh Media, which aims to explore historical and cultural roots in Dnipro, an industrial city in central Ukraine.

“We were told for so long, ‘You are Russian; any other culture besides Russian does not really exist.’ So now we are discovering what it means to be Ukrainian,” she says, citing a series of podcasts her organization is producing to uncover local traditions that were “buried under the Russian influence.”

“It’s a process of decolonization,” she adds.

Language and identity

For Maryna Goncharenko, an advocate of Ukrainian identity in Odesa, the journey began with what she describes as a “personal identity crisis” that set in when she was teaching English to Ukrainians in 2007.

That job got her thinking about the nexus between language and identity.

“I started questioning why we were all speaking Russian even though we are Ukrainian and are products of Ukrainian culture,” she says. “I concluded it wasn’t just me, that we were all having this cultural crisis. ‘We speak Russian; we know Russian culture,’ I said, ‘but we are not Russian!’”

Ms. Goncharenko says that by the time of the Maidan Revolution in 2014 – which ultimately ran the pro-Russia government out of Kyiv in favor of a pro-Western replacement – most of her generation identified squarely as Ukrainian, even though many still spoke Russian as their first language.

Then the full-scale invasion changed everything.

“The change was very abrupt,” she says. “It was the moment when people who were skeptical about speaking Ukrainian and identifying as Ukrainian made this massive shift toward using Ukrainian in public life.”

Moreover, the war set in motion a maelstrom of events and projects, from exhibits to lectures and public discussions, exploring identity and the dual importance of rediscovering history and memorializing the war and its impact.

Another popular topic in Ukraine’s current climate is decolonization of thought – which Ms. Goncharenko describes as a national effort to break free from Russian imperialism.

“In Odesa, we know our city is particularly precious for Russian imperialists. We have heard forever the blah-blah-blah that Putin considers Odesa the crown jewel of the Russian Empire,” she says. “That has led to a lot of discussion about reflecting on and rethinking the imperial narrative.”

Odesa before Catherine

Indeed, in Odesa’s central historic district, the marble pedestal that once supported a statue of Catherine II of Russia – long considered the founder of Odesa – now holds the sky-blue and sunflower-yellow Ukrainian flag. These days the monument is ringed by dozens of small Ukrainian flags placed in memory of fallen soldiers.

With missile barrages periodically striking the city, growing numbers of Odesans, including members of the influential business community, are asserting that their hometown was a vibrant Black Sea port long before Catherine came along.

“The myth is still strong that Odesa sprang to life on orders of Catherine II in 1794, but we feel it’s important to correct the myth and confirm that Odesa was a port and entrepreneurial center before it was occupied by Russia,” says Olena Matvieieva, coordinator of the Odesa Business Club’s Odesa Decolonization project. The club recently organized an “Odesa 600” festival that explored the many influences that have shaped the city over its six centuries of existence.

At the same time, some of the most active participants in Ukraine’s exploration of identity are keen to underscore that despite all the delving into the past, the national conversation is really about building a new future.

“We are moving in two directions during this war: We are discovering our identity and our past, but we are also looking toward the future,” says Mr. Zhadan, the writer in Kharkiv. “It’s important we remember that those two go together.”

Kharkiv must remember, he says, that it became Ukraine’s second-largest city based on its positioning as a border city between Russia and Ukraine, and as a result of the industrial base and the educational institutions that flourished there.

“Those are the strengths of the city that Ukrainians built,” Mr. Zhadan says. “So even if in this war the Russians destroy everything, it’s important that we build back a new Kharkiv, but one based on our roots as a city of education and of industry.”

Oleksandr Naselenko assisted in reporting this story.