Protest crackdown: UK democracy faces scrutiny over rights and freedoms

Loading...

| London

For holding a sign outside a courthouse reminding jurors of their right to acquit defendants, a retiree faces up to two years in prison. For hanging a banner reading “Just Stop Oil” off a bridge, an engineer got a three-year sentence. Just for walking slowly down the street, scores of people have been arrested.

They are among hundreds of environmental activists arrested for peaceful demonstrations in the United Kingdom, where tough new laws restrict the right to protest.

The Conservative government says the laws prevent extremist activists from hurting the economy and disrupting daily life. Critics say the arrests mark a worrying departure.

“The government has made its intent very clear, which is basically to suppress what is legitimate, lawful protest,” said Jonathon Porritt, an ecologist and former director of Friends of the Earth.

A patchwork democracy

Britain is one of the world’s oldest democracies, home of the Magna Carta, a centuries-old Parliament, and an independent judiciary. That system is underpinned by an “unwritten constitution” — a set of laws, rules, conventions, and judicial decisions accumulated over the years.

The result is “we rely on self-restraint by governments,” said Andrew Blick, author of “Democratic Turbulence in the United Kingdom” and a political scientist at King’s College London. “You hope the people in power are going to behave themselves.”

But what if they don’t? During three scandal-tarnished years in office, Boris Johnson pushed prime ministerial power to the limits. More recently, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak asked Parliament to overrule the U.K. Supreme Court, which blocked a plan to send asylum-seekers to Rwanda.

Critics say cracks have appeared in Britain’s democratic foundations.

As former Conservative justice minister David Lidington put it: “The ‘good chap’ theory of checks and balances has now been tested to destruction.”

Government takes aim at protestors

The canaries in the coal mine are environmental activists who have blocked roads and bridges, glued themselves to trains, splattered artworks with paint, sprayed buildings with fake blood, and doused athletes in orange powder to draw attention to climate change.

Groups such as Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, and Insulate Britain argue that civil disobedience is justified, but Mr. Sunak has called them “ideological zealots.”

In 2022, a statutory offense of “public nuisance” was created, punishable by up to 10 years in prison. The 2023 Public Order Act broadened the definition of disruptive protest, increased police search powers, and imposed penalties of up to 12 months in prison for protesters who block roads or other “key infrastructure.”

In May, six anti-monarchist activists were arrested before the coronation of King Charles III before they had so much as held up a “Not My King” placard. All were released without charge.

In recent months, hundreds of Just Stop Oil activists have been detained under a new rule that criminalizes slow walking protests. Some protesters have received prison sentences that have been called unduly punitive.

Structural engineer Morgan Trowland was one of two activists who scaled a bridge over the River Thames in October 2022, forcing police to shut the highway below for 40 hours. He was sentenced to three years in prison.

He was released early on Dec. 13 after 14 months in custody.

Ian Fry, the United Nations’ rapporteur for climate change and human rights, has called Britain’s anti-protest law a “direct attack on the right to the freedom of peaceful assembly.”

The Conservative government has dismissed the criticism. “Those who break the law should feel the full force of it,” Mr. Sunak said.

Even more worrying, some legal experts say, is the “justice lottery.” Half the environmentalists tried by juries have been acquitted after explaining their motivations. But at other trials, judges have banned defendants from mentioning climate change or their reasons for protesting. Several defendants who defied the orders were jailed for contempt of court.

Tim Crosland, a former government lawyer turned environmental activist, said the silencing of defendants “feels like something that happens in Russia or China, not here.”

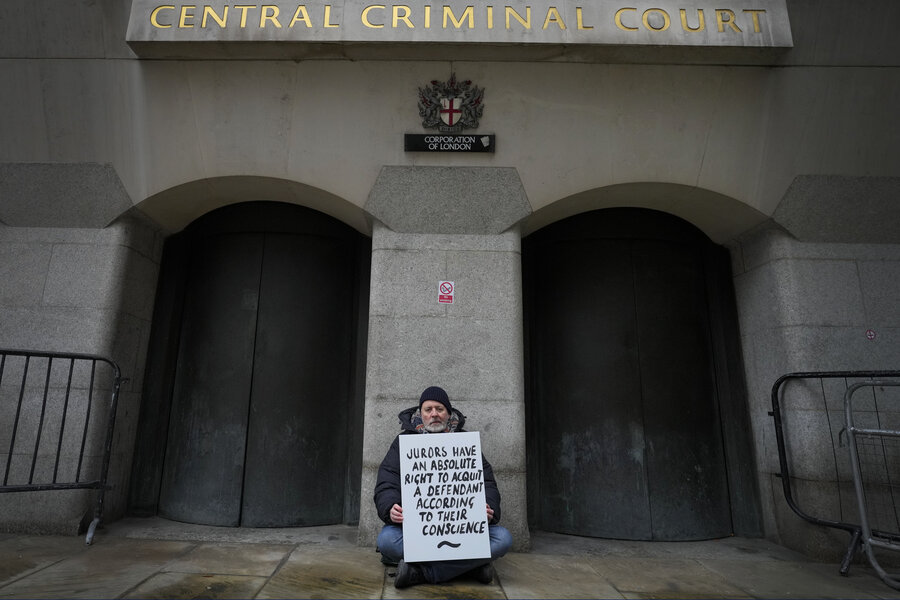

To highlight concern, retired social worker Trudi Warner sat outside a London court in March holding a sign reading “Jurors – You have an absolute right to acquit a defendant according to your conscience.” She is now being prosecuted.

Is Brexit to blame?

Many legal and constitutional experts say the treatment of protesters is a symptom of an increasingly reckless attitude toward Britain’s democratic structures that has been fueled by Brexit.

The 2016 referendum on whether to leave the European Union was won by a populist “leave” campaign that promised to restore Parliament’s – and by extension the public’s – sovereignty.

The divorce brought to power Boris Johnson, who tested Britain’s unwritten constitution. When lawmakers blocked his attempts to leave the EU without an agreement, he suspended Parliament – until the U.K. Supreme Court ruled that illegal. He later proposed breaking international law by reneging on the U.K.’s exit treaty with the bloc.

He was ejected from office by his own fed-up lawmakers in 2022 after a series of personal scandals.

“People were elevated to high office (by Brexit) who then behaved in ways which were difficult to reconcile with maintenance of a stable democracy,” said Mr. Blick, the King’s College professor.

The populist instinct, if not the personal extravagance, has continued. In November, the U.K. Supreme Court ruled that a plan by Mr. Sunak to send asylum-seekers to Rwanda was unlawful because the country is not safe for refugees. The government said it would pass a law declaring Rwanda safe, disregarding the court.

Former Solicitor-General Edward Garnier has likened the plan to lawmakers deciding “that all dogs are cats.”

But that doesn’t mean it won’t become law. Mr. Blick said that in Britain’s unwritten constitution, “nothing can actually be deemed clearly to be unconstitutional.”

Remedies have been proposed for Britain’s democratic deficit, including citizens’ assemblies, a new body to oversee the constitution and a higher bar for changing key laws. But none of that is on the horizon.

The protesters, meanwhile, say they are fighting for democracy as well as the environment.

Sue Parfitt, 81, is an Anglican priest who has been repeatedly arrested as part of the group Christian Climate Action. She has no plans to stop.

“It’s worth doing to keep the right to protest alive, quite apart from climate change,” she said. “It would be difficult for me to get to prison at 81. But I’m prepared to go.”

This story was reported by The Associated Press.